Eight minutes before the first and only vice-presidential debate, MSNBC's "Countdown" host, Keith Olbermann, and Newsweek's Howard Fineman were talking about "The View."

The opinionated, loud and very male Olbermann was making a point about how low Sarah Palin had sunk in America's estimation by playing a video clip of the daytime talk show's resident conservative Elisabeth Hasselbeck. Admitting that Palin's inability to name a single Supreme Court case besides Roe v. Wade was perhaps worrisome, Hasselbeck conceded, "That was a moment where she should have had some [examples] lined up."

Olbermann and Fineman chuckled at the possibility that, as goes Elisabeth Hasselbeck, so goes the country. "This is not my usual turf," said Fineman.

It sure isn't. But this isn't anybody's usual campaign, and what the (still mostly male) political pundits are coming to grips with is that the election cycle is not just playing out on their news shows and their 24-hour networks but also in the traditionally feminine -- and therefore traditionally marginalized -- world of daytime television.

Credit Sarah Palin, or Hillary Clinton, or unprecedented excitement over the historic candidacy of Barack Obama and appreciation for his exceptionally appealing wife. Maybe it's the panic about the financial crisis, outrage at the mishandling of the war, fury over gas prices, worries about the environment -- all of which are so powerful that they're causing the election to seep into unexpected cultural corners, like Us Weekly and porn. Whatever the reason, daytime talk shows have showcased some of the most sophisticated (as well as some of the most mind-numbingly stupid) conversations about what's happening on the political stage this season.

For example, when you hear people on television these days discussing the Wall Street crisis and someone makes the incisive point that when the Feds give money to Wall Street executives, it's called "a bailout," but when they give it to regular citizens, "they call it socialism," you might not be listening to Maddow and Buchanan or Hannity and Colmes but to Whoopi Goldberg and Joy Behar, who conducted just this conversation -- along with "View" co-hosts Hasselbeck, Barbara Walters and Sherri Shepherd -- in early October. And all before smoothly segueing into an interview "with the fabulous Alec Baldwin."

And when somebody tosses a political zinger, it might just be Sherri Shepherd, who used to have the least to say politically on the show but is now letting loose like she did on Oct. 6, when Goldberg commented on Obama's graying hair, and Shepherd quipped, "Every little bit of white helps."

Strange as it may seem, daytime has historically provided some of the most progressive television in the nation. Long before prime-time TV made room for meaty female characters, soap operas were spinning out stories in which women were central characters. Soaps also provided many of television's groundbreaking story lines -- Erica Kane's 1973 abortion on "All My Children," the introduction of a gay character, Hank Elliott, on "As the World Turns" in 1988, "General Hospital's" Stone battling AIDS in the 1990s -- made more powerful by the narrative intimacy afforded by the daily serial format.

But it wasn't just soaps that pushed the envelope. Phil Donahue's daily talk show, which ran from 1970 to 1996, focused on topics from atheism to sexuality to Soviet-American relations during the Cold War. Married to "That Girl" feminist icon Marlo Thomas, Donahue focused on the women's movement. Donahue once told the L.A. Times that he owes his success to the fact that he "discovered early on that the usual idea of women's programming was a narrow, sexist view. We found that women were interested in a lot more than covered dishes and needlepoint."

Post-Donahue, there was a devolution in the level of political discourse on daytime; in its place was a spate of shows devoted to personal drama. Hosts like Sally Jessy Raphael, Ricki Lake and, most famously, Jerry Springer populated the airwaves with battling couples, faked paternity tests, revelations of cheating partners, a lot of hair pulling and, on Springer's show especially, some lusty throwing of chairs. But whatever else there is to say about this genre, it did what little else on television or the movies was doing: It gave a voice and a face and a stage to portions of the American population who otherwise had no outlet for expression -- the poor and the working class, as well as gay and transgendered people, transsexuals and other sexual nonconformists.

And, of course, for decades daytime has been the home of culture-changing Oprah Winfrey, who made blackness, and black womanhood, not only visible in the lily-white mainstream media -- not only acceptable, not only likable -- but also deeply and powerfully relatable. Were it not for Oprah Winfrey, we might not have Barack Obama as our Democratic candidate for president, both because of her early endorsement of his candidacy and also because of her presence and power in American culture.

This makes it all the more fascinating that, as the daytime airwaves flash with political conversation, Winfrey is comparatively silent. In the past, she has invited candidates from both parties on her show, but because of her early and open support of Obama, she has decided not to host any of the presidential candidates. As she told reporters, "At the beginning of this presidential campaign, when I decided that I was going to take my first public stance in support of a candidate, I made the decision not to use my show as a platform for any of the candidates." This has created an odd dynamic in which one of Obama's most powerful supporters is unwilling to use her considerable forum to show her support, even at the height of election season.

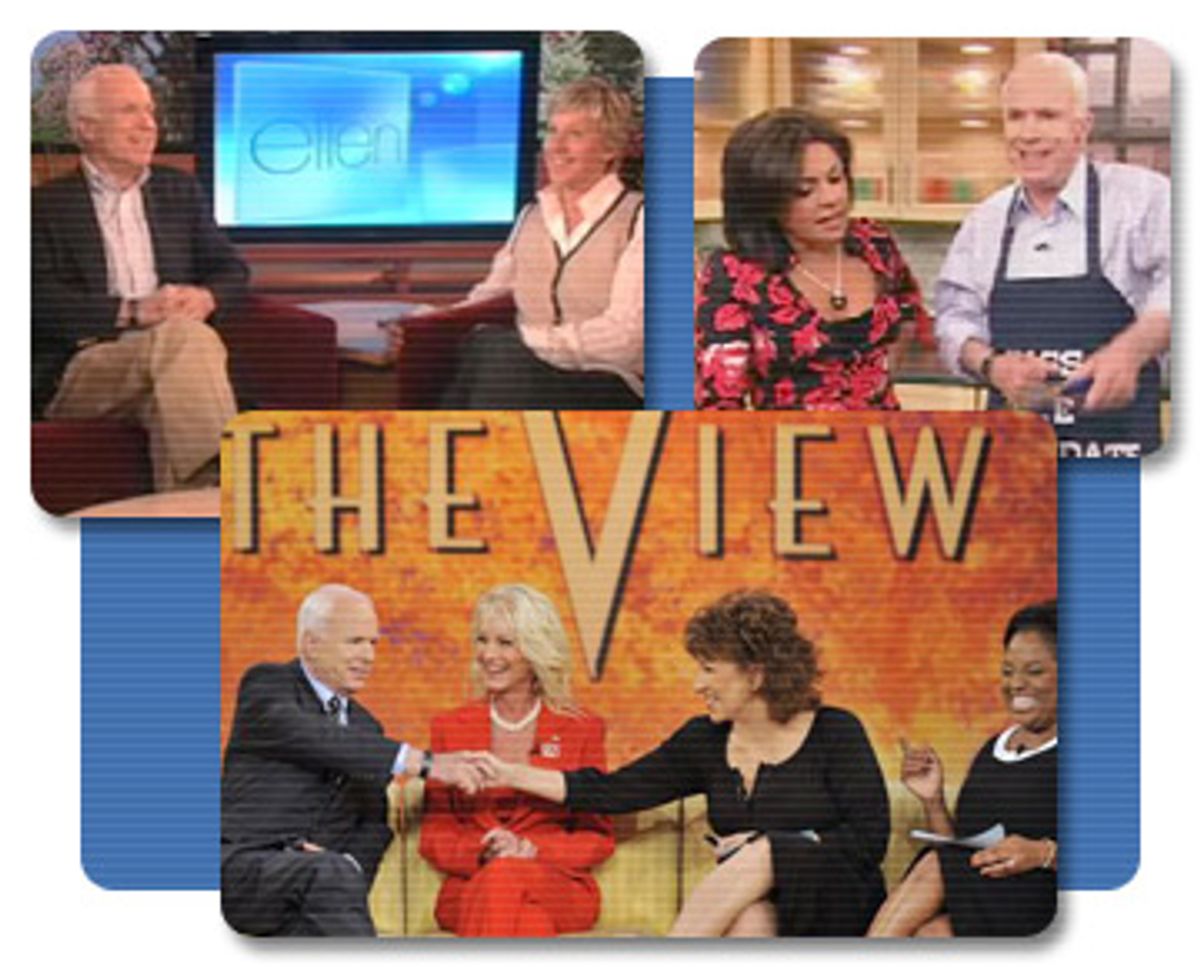

But the Oprah vacuum has created more room for other daytime hosts to get in on the electoral act, not to mention more incentive for candidates to visit shows besides Winfrey's if they want to reach daytime audiences. Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton and John McCain have all been guests on Ellen DeGeneres' talk show; McCain and Bill Clinton have taken their lumps on "The View," while Michelle Obama made her first post-primary splash there in June, and in April, during Obama's appearance, Barabara Walters told him he was "very sexy-looking." Then again, McCain practically received a massage when he showed up with his wife, Cindy, to cook ribs with Rachael Ray, when the 30-minute chef and presidential candidate even made the dubious pronouncement that he buys his ribs at Costco -- just like you!

There seems to be an added incentive for candidates to show up and shill on daytime this year, in part because Clinton's candidacy and all it entailed made clear that the women's vote, and women's views, were in fact going to matter to the outcome of this election. It doesn't hurt that, between TiVo and the Internet, the daytime audience (after years of contracting) has grown exponentially in recent years, if not for entire episodes of programming then for choice moments. News sites, fashion sites, feminist sites, humor sites -- they can now all posts clips from talk shows so that those with day jobs can catch what they missed while they were gone from home. The shows need to up their game in order to increase Internet visibility and play to a broader audience.

But it's not simply the audience demographics of daytime that have changed. It's also the face of daytime hosts. Ellen DeGeneres, unceremoniously bounced from prime time after her emergence from the closet, found a home on daytime in 2003 and an audience that loved her, gay or straight. And at "The View," the wild ride of Rosie O'Donnell's year-long tenure helped to tune an audience ear to the sound of loud and left-leaning political commentary. The show, thanks to its founder, Barbara Walters, and original moderator, Meredith Vieira, always had a newsy bent. But during Rosie's time there, "The View" became a forum for shouting matches, often about controversial topics and vociferously voiced partisan opinion. Rosie, of course, was replaced by Whoopi Goldberg -- a less divisive but almost as bolshy presence.

It is still relatively safe for guests, and political candidates, to expect the friendly, kid-glove, recipe-heavy/policy-light treatment that McCain received when he appeared on Rachael Ray, when the host asked him about making American diets healthier before allowing him to crow about his proficiency on a barbecue (or the treatment Obama received from the moony ladies at "The View," or on "Ellen," when DeGeneres gave him a light dance-and-chat). But it has recently become more common to see politicians, especially John McCain, made uncomfortable by the directness of the conversation on daytime television, a directness that isn't often found in the more traditional news media.

DeGeneres, who keeps most of her show politically benign (and for the first few years didn't often mention her lesbianism), has of late made much more of her sexuality, broadcasting video this summer of her wedding to actress Portia de Rossi. Last May, DeGeneres subjected McCain to one of his most uncomfortable interviews, using her upcoming nuptials as a platform on which to grill the candidate about the issue of gay marriage. It should be noted that DeGeneres also questioned Hillary Clinton about her feelings about gay marriage, and that McCain's willingness to appear on DeGeneres' show at all was notable, given his attempts at the time to court the conservative base of his party.

"Let's talk about the big elephant in the room," DeGeneres said, explaining that she had already been planning to have a commitment ceremony but that, because of the California decision to legalize gay unions, "it just so happens that I legally now can get married, like everyone should." Her audience clapped as she asked McCain for his thoughts on the topic.

"I think that people should be able to enter into legal agreements and I think that is something we should encourage, particularly in the case of insurance," said McCain. "I just believe in the unique status of marriage between man and woman. And I know we have a respectful disagreement on that issue."

Here DeGeneres persisted: "We are all the same people. You're no different than I am. Our love is the same ... When someone says, 'You'll have a contract, and you'll still have insurance ... it feels like someone saying, 'You can sit here, you just can't sit there.'"

McCain was left to say only, "I've heard you articulate that position in a very eloquent fashion. We just have a disagreement and I, along with many many others, wish you every happiness."

It was a glimpse at what the daytime format makes possible: a breezy, casual, personal exchange as vehicle for a larger social conversation. The moment packs a wallop in part because the heft of the encounter is a surprise, and in part because it is delivered by a host, like DeGeneres, whom viewers feel they know intimately and trust. Instead of watching a political pundit conduct an inside-baseball transaction with a candidate, an audience can feel as if a friend has just asked the questions.

Since her McCain interview, DeGeneres has stuck to her bipartisan good cheer, using what influential cultural power she wields to get people to register to vote. On Oct. 2, the last day before many voter registration deadlines, she welcomed Leonardo DiCaprio to preview a public service announcement they'd made together (along with Dustin Hoffman, Sarah Silverman, Ashton Kutcher, Forest Whittaker and others) encouraging people to register. And she's been hawking "Laugh. Dance. Vote." T-shirts and boxers on her show.

If there is any remaining doubt about which candidate might mirror DeGeneres' political positions (on gay marriage and animal protection, another passion) and which candidate's prospects might benefit from increased voter turnout, DeGeneres has also tipped her hand (subtly) by allowing some of her more partisan guests to get their digs in. "It's like they scoured America for a woman," said reality star Sharon Osbourne on a September episode, in reference to Sarah Palin, "and the last stop before you fell off America was Alaska, and there she was, iced, waiting ... It's like she was a last resort ... They want women to vote for her, but women aren't that stupid."

This last line provoked wild cheering as DeGeneres nodded, "Uh-huh, uh-huh."

And however easy Rachael Ray was on McCain, it's only fair to point out that she also fluffed Michelle and Barack Obama, telling them in early August, "I just wanted to say it is such an exciting, wonderful time to be an American, and I think your campaign really has created this great wave, this great fervor." In the ensuing interview with Michelle, Ray asked innocuous questions about whether the couple gets date nights (they do) and what "their song" is (Nat King Cole's "Unforgettable" and Stevie Wonder's "You and I").

But none of this holds a candle to what has been going on at "The View," where ringleader and show creator Barbara Walters has, as reported by Jacques Steinberg in the New York Times, been making "a conscious effort to insert their daytime talk show forcefully into the nation's political conversation this fall."

It's worked.

Consider John McCain's much-discussed Sept. 12 appearance on the program, which began as he settled comfortably and confidently into the couch. By the time the interview ended, he had conceded that he did not want to reenslave black people and weathered sharp questions about how many earmarks Sarah Palin had put in for as Alaska governor. As his wife, Cindy, later complained to a rally, the daytime hostesses with the mostest had "picked our bones clean." Indeed, it was the finest and most direct questioning John McCain has received during his campaign, or on the issues, from anyone in the mainstream media.

The conversation with McCain was powerful enough to prompt former President Bill Clinton to get himself booked on the show. And while the women treated him with a bit more reverence, they did stick him with some honkingly direct questions -- about whether he or his wife had wanted Hillary to be Obama's running mate, about what Clinton thought of Palin -- that were controversial enough for Clinton to make news by answering them (with his current tone-deaf ambivalence about the election).

But most mornings on "The View," neither presidential candidates, nor their spouses, are on the couch. Most days, the first 10 minutes are devoted to frequently high-pitched arguments about the day's headlines, the election and the financial crisis in which everyone is involved -- including Sherri Shepherd, who once admitted that she had never voted before. These are conversations that often prove the hosts to be well-informed and opinionated. These ladies are a regular "McNeil-Lehrer News Hour" for the late-morning set, with Hasselbeck as the benighted Republican bugaboo.

On an early October episode, Goldberg kicked things off by suggesting that, "If we were gonna be surging anywhere, we should have surged our behinds into Afghanistan!" and chiding McCain for relying too heavily on the success of the surge as a talking point.

Soon Hasselbeck was yelling words like "Rezko! Ayers!"

"No, excuse me," interjected Shepherd, who seems increasingly radicalized, especially in response to Hasselbeck's conservatism. "McCain was involved in the Keating Five."

Behar shouted, "You go, Sherri!"

When Behar, whose investment in this election has landed her repeatedly on "Larry King Live" and who was (somewhat depressingly) dubbed by the New York Times' Frank Rich as "the new Edward R. Murrow" after the McCain interview, brought up the clip of CNN's Campbell Brown lighting into the "sexist" McCain campaign for keeping the media away from Sarah Palin, Walters said, "I don't think it's because she's a woman. I think it's that they fear she may make a mistake because she's uninformed."

Behar countered, "If she were an uninformed male, would they allow her to speak to the press?"

Walters replied, "If it were an uninformed man they might have the same barrier." And then, Rachel Maddow-style, to some unseen McCain campaign entity: "We would like to say, once more, that we would like to have Mrs. Palin on the program."

Best of luck with that request, ladies!

After last week's vice-presidential debate, Hasselbeck had (unsurprisingly) recovered from her moment of doubt about Palin's capabilities. She asserted that the Alaskan governor had done a good job. Shepherd, meanwhile, was dismayed by Palin's refusal to answer moderator Gwen Ifill's questions, and Walters found the whole thing utterly unrevelatory, although she was bothered by the fact that Palin brought young Trig onstage so late at night.

When Hasselbeck groused about how, like any mom, Palin probably just wanted her kids around her, Shepherd cut her off: "Barbara didn't say she was a bad mom!" she corrected. It wasn't long before Hasselbeck returned to her favorite complaint about Obama: his associations with Weather Underground co-founder Bill Ayers.

"Bill Ayers surrendered," Goldberg said, explaining gently, for the umpteenth time, to Hasselbeck that "he, like a lot of us in a certain generation, were pissed at the United States of America. Some were more radical than others ... he turned himself in. I assume he rehabilitated himself. I don't recall anyone in 2001 saying, 'Let's go get Bill Ayers because he's a terrorist.'"

Soon came conversation about how people's pasts are people's pasts, and that McCain had his own Keating past. "John McCain was cleared of any charges!" said Hasselbeck.

"It was poor judgment," said Walters.

But Hasselbeck was undeterred. "This is what bothers me truly about Barack Obama," she said. "He wants to hide all of his radical connections."

"It's crap," said Goldberg.

"It's not crap," shot back Hasselbeck.

"It's crap," repeated Goldberg, officially, sending the program to commercial while the crowd cheered wildly.

Shares