"As Lincoln said to a nation far more divided than ours: We are not enemies but friends ... Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection." -- Barack Obama, quoting Abraham Lincoln

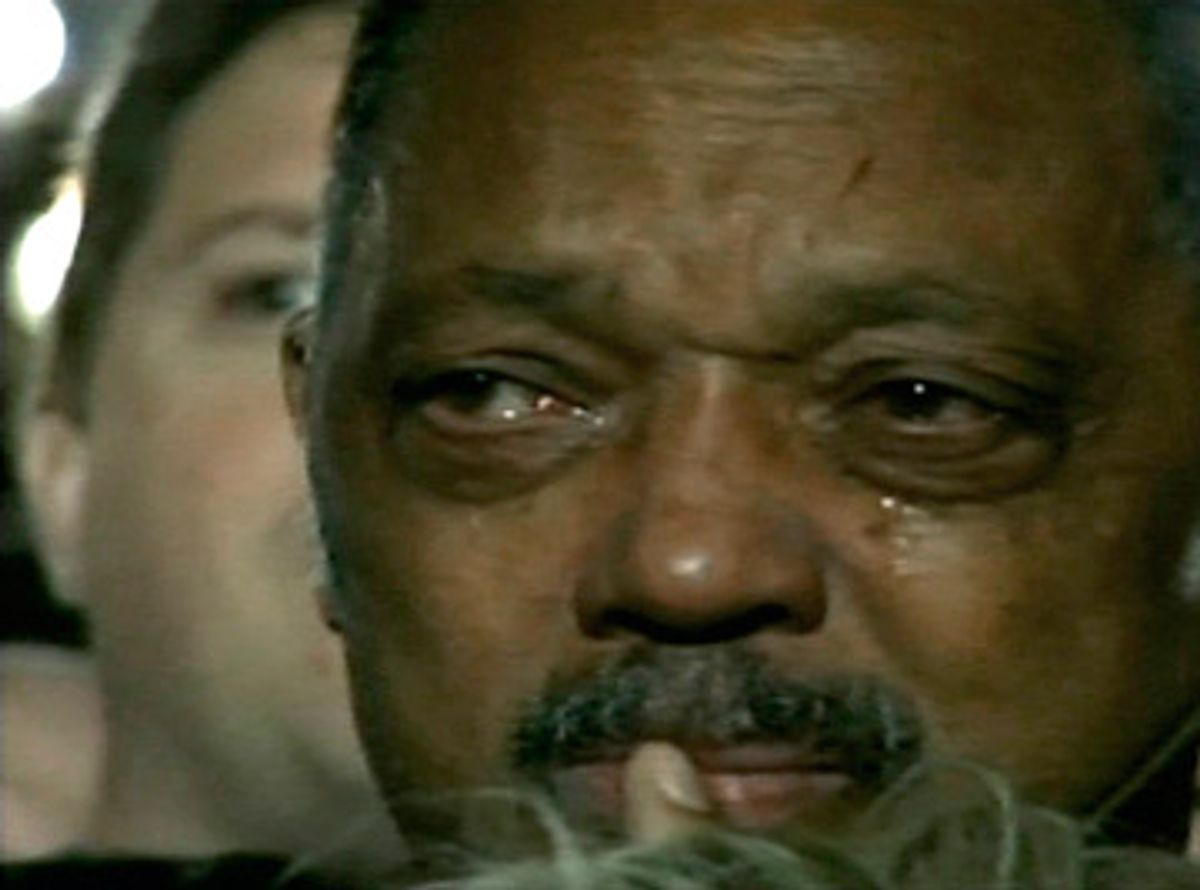

Perhaps it was strange, or perfectly appropriate, that it was Jesse Jackson's face that provided the widest and most transparent window into the quicksilver emotions of the night, the year, the new century and the new America. Jackson, whose image flashed on CNN soon after 11 p.m., in the moments after networks declared victory for Barack Obama. Jesse Jackson, who earlier this year failed to hide his frustration with the young man he was in Chicago to celebrate, who did not make a speech at the Democratic convention, whose legacy was tarnished or even forgotten in 2008's mad rush toward progress, was in the mammoth crowd in Grant Park in Chicago.

And in those first moments, he looked hardened, paralyzed -- by disbelief, or regret, or sadness, or surprise or something that was certainly not yet fully realized joy. It was easy to read on his closed face a million imagined emotions: that his momentary reticence was born of the resentments grown up during what was, on so many generational and social and personal levels, for so many kinds of people, an absolutely harrowing race for the American presidency. In two years, the youth and eloquence and persuasive power of Barack Obama and his rocket-fueled campaign have steamrolled everything in their path: from racial bias to ideas about how to win presidencies to a Bradley tank of a primary opponent to a long-held feminist dream to the delicate reverence with which Jackson's generation of civil rights activism had been held.

Obama charged headlong through all of it, blasting to smithereens that which would impede him, while crafting his campaign on the shoulders of what had come before him and could be useful to him. Obama's win on Tuesday would probably not have been possible without the new and often uncomfortable dialogue about race, without the fire forging of the primary competition with Hillary Clinton, and certainly not without the work and sacrifices of Jackson and his generation of aging or long-departed activists, men and women (but mostly men), who did not appear onstage with the president-elect, but who sat in and marched and protested so that Americans like Obama might be treated as Americans. Tonight, Jackson was standing in for so many of his compatriots, a spectator, a mere witness to the momentous history he'd given his life to make possible.

Watching him, you couldn't help thinking of the kinds of generational tension that these two years of enormous change -- so swift and sudden sometimes we haven't even been able to properly record it, let alone comprehend it or credit it to those who built the groundwork for it -- have evoked. During this year, in which like-minded groups of people were forced to compete with and among each other for a rare, unprecedented seat at the presidential table, there has been, among African-Americans, women, the young and the old in progressive America, far less hand-extending and hat-tipping than there has been finger-pointing and back-turning. And whatever Jackson may actually have been feeling in those first post-victory moments, it was not hard to see this pain written on his face.

But not 20 minutes after the news of Obama's victory had begun to sink in, the cameras again panned to Jackson, and this time his cheeks were wet with tears, his hand at his mouth. He still looked anxious, and tense, as if he, like so many of the people around him wandering saucer-eyed and silent, were still wound tight with fear: Is this happening? Is it real? And if so, can I begin to weep?

But the tears -- on Jackson's face, and on many of our faces -- are real, as is Obama's victory, as perfect and imperfect, back-achingly difficult and mind-bendingly easy as it's been. Here in Brooklyn, N.Y., there are fireworks down the street and people cheering as they run up the sidewalk; from the roof of my building, you can see that across the East River, the Empire State Building has been lit up blue. This is happening. America has cracked open.

And all those fireworks and whooping had started even before our young, handsome president-elect, who looks so much like his white grandfather but is (we can say it now, acknowledge it, stop being scared of it) also black, took the stage with his family. His family that is stunning, and, yes, black too. They're our first family now, and as they stood in front of more than 100,000 people, they became the faces of a brand-new, fresh chapter in this country's history. It was ironic that the Democratic Party's rebirth was happening on a stage in Chicago, the city where it died -- or was badly injured anyway -- 40 years ago. And on the day after the passing of a grandmother who raised a boy who had no historical reason to believe he could win the presidency of the United States.

And so it made perfect, unyielding sense when Barack Obama opened his speech with the assertion that "if there is anyone out there who still doubts that America is a place where all things are possible, who still wonders if the dream of our founders is alive in our time, who still questions the power of our democracy ... tonight is your answer."

How could Jesse Jackson not cry, standing in that crowd, realizing that whatever hurt time and generational difference might have inflicted on his project and his legacy, he was witnessing the dawn of a world that his work made possible, but that he had not been able to make possible himself.

And then he began to wave a small American flag on a wooden stick, like a kid at a Fourth of July parade. Elsewhere in the crowd was Oprah Winfrey, that most almighty American who, like Jackson, helped launch Obama's dream, but who on the night it was made manifest was simply a member of a throng that could only look on and weep as the uneven ground on which America was built became slightly more level beneath their feet.

The passions of this time may well have strained all our affections, but our bonds are stronger than ever.

Shares