It's a tough mission that critic Ken Tucker has set himself in "Scarface Nation": to apotheosize and assay and cogitate over a movie that ... is not very good. At all. At least not by the critical standards we grown-ups are supposed to apply to the film form. We're supposed to hoist our delicate noses in the air and point out that "The Godfather" saga and "The Sopranos" series are far more profound depictions of the mobster soul than this "Scarface" creature and that "The Wire" is an infinitely more complex study of crime's intersection with poverty and that pretty much everything accomplished by Brian de Palma's 1983 cult classic has been done more subtly, more thoughtfully, more humanely by someone else.

Oh, screw it: A quarter-century after its birth, "Scarface" lives on, for all its vulgarity. Or is it because of its vulgarity? "There is something unshakably low-down and seedy," writes Tucker, "disreputable and sneaky, about 'Scarface' as a piece of art, an antistatus that only adds to its pervasiveness and longevity."

Piece of art, did he say? The same movie where Al Pacino buries his face in pile-high drifts of coke and emerges looking like a white-nosed coati? The movie with that trashy robo-disco Giorgio Moroder score that already sounds as dated as the theme from "Love Story" and the tapestry of profanity so dense you can actually watch a two-minute version of "Scarface" consisting entirely of the word "fuck" and find it every bit as intelligible as the full-length film?

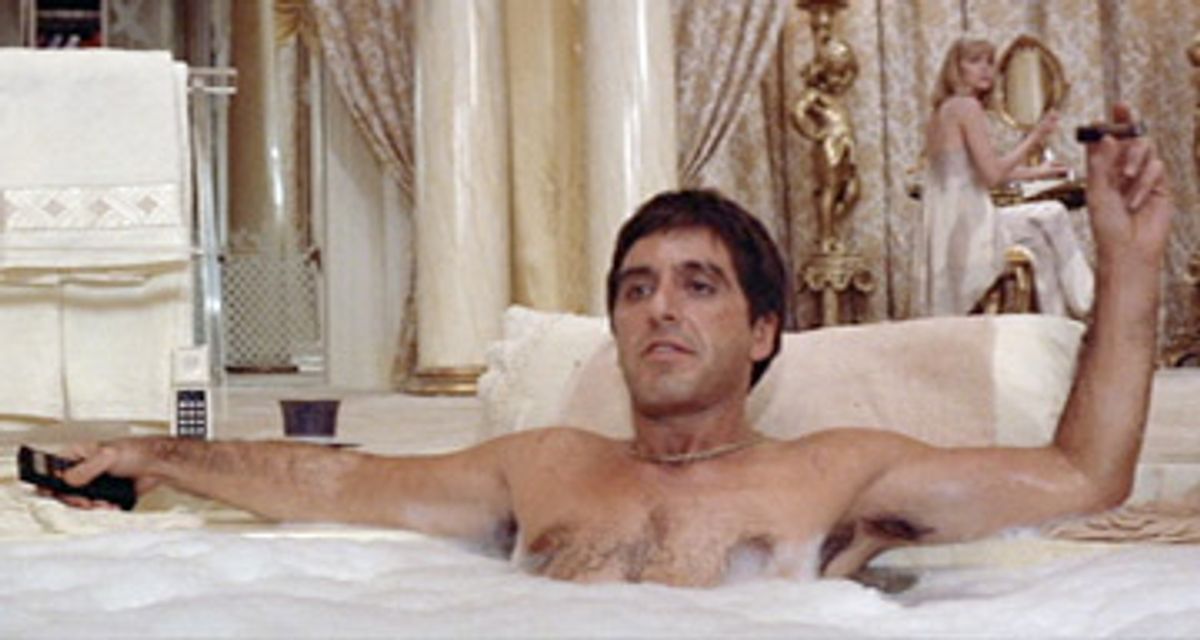

Oh, sure, have your laugh, says Tucker. "'Scarface' absorbs ridicule and overexposure and just keeps on going." Very much like its protagonist, Tony Montana, a Cuban thug exiled to Florida in the 1980 Mariel boatlift. Crafty and ambitious, Tony enlists as a soldier with Miami drug kingpin Frank Lopez (Robert Loggia) and bides his time until he can eliminate his boss and claim the boss's mistress (the affecting Michelle Pfeiffer). But even as he becomes king of the local drug trade, he grows crazier and more paranoid, and at film's end, having killed or alienated his loved ones, he's left alone to stage-manage the spectacle of his death. And what a death! A Christ-like swan dive into a swimming pool, from which Tony ascends not to heaven, as Tucker writes, but to "the kingdom of pop, where all things exist in an eternal present."

"Scarface" was only a modest commercial success when it was first released. The reception from critics was frosty: Even Pauline Kael, a longtime water-carrier for de Palma, dismissed the film as "an allegory of impotence." Many viewers were repelled by the movie's language and violence (at one key juncture, Tony is forced to watch his friend dismembered by a chain saw) and by the overkill that seemed sewn into the film's very fabric. The final sequence, by way of example, features what appears to be the entire population of Colombia pouring into Tony's ineffectually guarded mansion. As the film's screenwriter, Oliver Stone, puts it: "That's a Hong Kong action-film shoot-out before its time, right?"

Something else before its time: de Palma's decision to dispense with film noir shadows. "If a violent act is going to occur," he instructed cinematographer John A. Alonzo, "the surroundings should be bright, not dark." The resulting pastel, keyed to Florida's neon colors, signified a new order of moral rot and would soon be encoded and formalized via "Miami Vice."

"Scarface" is nothing, finally, without the catchphrases that Stone salted so liberally into his script. Some seem to issue from a street-MBA program: "Don't get high on your own supply ... First you get the money, then you get the power, then you get the women." Some have the flavor of personal credo: "I bury those cock-a-roaches ... All I have in this world is my balls and my word." My personal favorite is Tony's admiring assessment of Miami: "This town like a great big pussy, waitin' to get fucked."

But undoubtedly the line that has given "Scarface" its permanent place in pop culture comes when Tony straps on a bazooka roughly the size of a mature oak and prepares to rain down death. "Say hello to my little friend!" he snarls. Although, by the time it makes it past Al Pacino's lips and tongue, it sounds more like "Say yello to my lee-ul fren." Either way, it's irresistible: an explosively funny exercise in phallic worship.

We can see, then, that the phrases "Tony Montana" and "cinematic treasure" are never going to be yoked in the same sentence. "Scarface" owes its immortality, anyway, not to traditional tastemakers but to a devoted cult of young black and Hispanic men (a few women, too) who seized it for their own. Its arrival coincided with the gangsta phase of rap and hip-hop, and the film's various tropes -- "the ostentatious jewelry, the glorification of drug-taking as well as drug-selling, and the images of women as near-naked arm-candy" -- have been staples of music videos ever since. As one observer put it, "All these rappers are out there rapping about how much money they got, and all the drugs they sell -- that's who they're emulating: They're living their little Tony Montana dream."

Tony's second-class status, coupled with his ruthless pursuit of the American dream, spoke with ferocious directness to a whole generation of street kids, not to mention celebrities. Snoop Dogg watches the movie at least once a month; Sean "Diddy" Combs has seen it at least 63 times; Shaquille O'Neal celebrated his 34th birthday with a Scarface party. No episode of the MTV series "Cribs" is complete without some musician pointing pridefully to a Scarface photo collection or a set of Scarface window blinds or an exact replica of Tony Montana's white sofa.

This cross-cultural identification has exacted a rather large price, as Tucker is careful to note. The misogyny that drives so much gangsta rap, for instance, derives in part from de Palma's reduction of women to "disco dollies and white-silk fantasy figures." And the dubious ethos that Tony Montana supposedly lives by manages to obscure the fact that he's a coldblooded killer. "How many young lives -- urban and suburban -- might be less caught up in criminal behavior had 'Scarface' not codified a certain set of rules to live (and die) by?" asks Tucker.

Tucker's a bit too eager, maybe, to paint a trail of blood from "Scarface" to the ghetto, but I confess that just when I thought he was overstating the film's influence, a Netflix ad popped across my computer screen, and there it was: Tony Montana in his white disco suit. "Chi Chi!" I nearly cried in homage. "Get the yeyo!" Today, Al Pacino's ravaged face glowers forth from T-shirts, shower curtains, shirts, jerseys, hooded jackets. "'Scarface,'" writes Tucker, "is the only movie that is its own franchise."

An editor-at-large with Entertainment Weekly (who, I should disclose, once favorably reviewed a book of mine), Tucker does an expert job of tracking "Scarface's" provenance, from Armitage Trail's 1930 novel to Howard Hawks' 1932 film version (a far more concise work than de Palma's remake and, in its day, nearly as controversial) all the way to "The Untouchables" and such end-of-the-pipeline effluents as comic books, video games and ringtones. Tucker is an astute and persuasive and deeply informed cultural observer, and in "Scarface Nation," he has tucked just the right amount of tongue into his cheek.

The only thing he couldn't convince me of was the movie's esthetic value. "A great shallow masterpiece of pop," he calls it, "a work of diverse, mongrel artistry." I take this to be a nice way of saying "trash." Lively trash, to be sure, but when Tucker goes on to suggest that "As soon as you see it, you want to experience it again," well, that's when I get off the bus. I've seen it twice, and each was enough to last me a decade.

What makes it so exhausting, I think, is Pacino. He's in virtually every scene, and like Paul Muni, who played Tony in the original film, he is in hock to his own ambition. His performance suggests that it's not enough to be good, a great actor must be Great. This determination is so at odds with the pseudo-operatic silliness of "Scarface" that it produces camp at fairly regular intervals.

Contrast the extravagant surface effects of this movie with Pacino's minimalist work in the second "Godfather" installment, where he limns the death of Michael Corleone's soul with such precision that your own soul seems to freeze in response, and you'll see that something truly sad died with Tony Montana: a great actor's bullshit detector. All things considered, I can just about forgive Scarface. I'm not sure I can forgive "Scarface."

Shares