The detainee held on charges related to the so-called war on terror is clad in an orange jumpsuit. His wrists are shackled to a leather belt cinched tight around his waist. A short chain connects his ankles, so he can only shuffle down the barren hallways of the prison, escorted by a guard at each arm.

He has spent more than 29 months in solitary confinement over the past four years, allowed out of his narrow cell during some of that period only to stretch his legs, alone, for one hour a day. In solitary, he has almost no contact with other human beings. He is allowed no radio, no TV and, in a disorienting twist, no watch or calendar to mark the brutal grind of passing time.

With so little stimulation, the brain begins to work against itself. Prisoners in solitary have described delusions, even hallucinations. It can drive a man mad.

"Karma really is a son of a gun!" says Charles Graner, infamous as the torturer of Abu Ghraib, in one of several letters he has written me from Fort Leavenworth, Kan., where he has been incarcerated since his conviction in January 2005 on charges related to the abuse of Iraqi prisoners at the U.S. prison in Abu Ghraib, Iraq. "Add a couple of years, change the color of my uniform and I find myself in the same position."

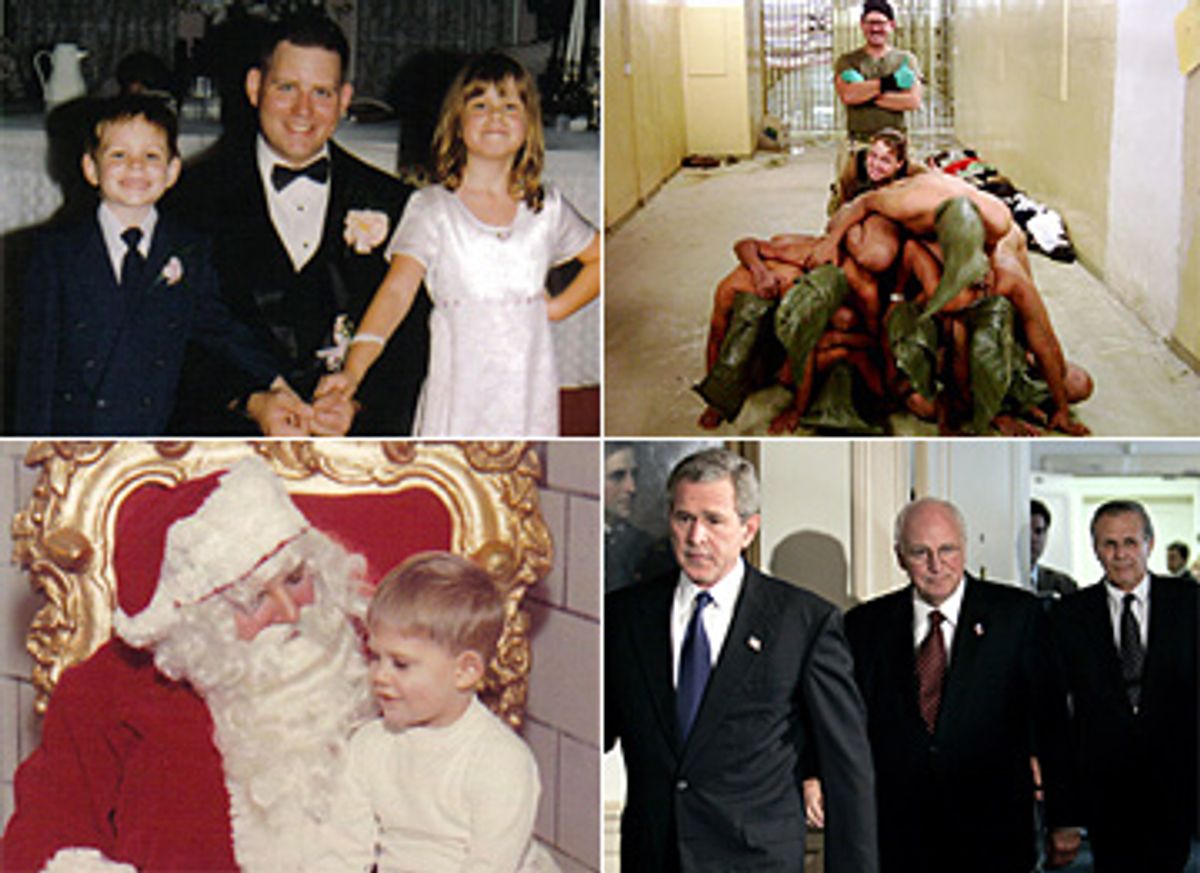

You remember Graner, the alleged ringleader of abuse at Abu Ghraib who showed up in those harrowing photos back in 2004. He was the mustachioed man grinning eerily back at the camera, giving a thumbs up as he stood over the body of dead prisoner. The pictures remain some of the most notorious images from the war. He and other soldiers at Abu Ghraib forced prisoners into stress positions and frightened them with dogs, stripped prisoners naked, put hoods and women's underwear over their heads. Graner, a 36-year-old reservist from Pennsylvania, faced 10 counts under five charges: assault, conspiracy, maltreatment of detainees, indecent acts and dereliction of duty. He was found guilty on all counts, except for one assault count that was downgraded to battery, and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

After staring at the image of a naked, humiliated detainee with a bag over his head, it is easy to argue that Graner deserves whatever he gets. But Graner is now the only person involved in the Abu Ghraib scandal who is still behind bars. Of the eight other enlisted military personnel whom the Army tried and convicted in courts-martial in connection with the abuses, none is now in prison. (The sole officer who was tried was acquitted.) Staff Sgt. Ivan Frederick, the other alleged ringleader, got eight years, but his sentence was commuted and he is out of jail. Pfc. Lynndie England is not in jail. Everyone but Graner is free.

Years of revelations, however, show that the prisoner abuse started at the top, yet nobody who ordered the abuse has ever been tried or convicted of anything. The Army convicted a handful of soldiers from Abu Ghraib in courts-martial focused almost exclusively on acts captured by the soldiers' own digital cameras, not on policy decisions from above. As the nation prepares to change presidents, the administration that sanctioned, encouraged or ordered the abuse of prisoners taken in the war on terror is about to leave office, having long ago decided that no one in a position of authority will be held accountable. The incoming Obama administration is still wrestling with how it will deal with this legacy; as Salon was the first to report, there may be a torture commission that will weigh whether to prosecute both the perpetrators of torture and the architects of the policy under which the abuse took place. As Salon was also the first to report, there may be no criminal prosecutions at all.

Does Graner deserve jail time while Vice President Dick Cheney prepares to reenter private life, and former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld puts the finishing touches on his memoirs? In one of his letters to me, Graner once wrote that the difference between him and Rumsfeld is that in Graner's case, "the pictures came out."

Mary Ellen O'Connell, a professor of international law at Notre Dame Law School, believes that Graner belongs in prison. But she has also been discussing with colleagues, and debating in public forums, the viability of prosecuting Bush administration officials for torture, and she is troubled by the double standard.

"There were failures at the top that led to Abu Ghraib and Graner's conviction," O'Connell said. "The fact is that there is good law to hold these individuals accountable. So why aren't we holding everyone accountable who is implicated?"

"They all did what they were told," said Irma Graner, mother of Charles, of her son and the other soldiers at Abu Ghraib. "And the ones that told them to do it escaped everything."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The steel and glass of downtown Pittsburgh don't melt slowly into suburbia, but end relatively abruptly. Drive south out of downtown for just a few minutes and you are winding through the hairpin turns and steep, evergreen-lined hills that made up the domestic backdrop for the 1978 film "The Deer Hunter."

Several miles north of Clairton, where some of that movie took place, sits the modest two-story home where Graner grew up, nestled in a tidy suburban neighborhood, the kind where everybody knows the mailman's name.

A wide living room window dominates the front of Graner's childhood home. Taped in the middle of the window is a photo about the size of notebook paper: a young Marine in his dress uniform, looking stern and tough for the camera. It is a young Graner in the Marine Corps, years before he joined the Army.

Charles senior, Graner's father, goes by the name Red. He has a warm, welcoming demeanor. He works for U.S. Airways' maintenance control. Graner's mother, Irma, a gentle, soft-spoken woman, raised Graner and his two sisters. Both parents waited at the front door when I walked up the drive one day late last summer, past the photo of their son in the window.

"People are finally realizing that [the orders for abuse] came from the top," Red said hopefully as the three of us sat at the Graners' polished wooden dining room table. "We knew it all along."

We thumbed through pictures of Charles Graner Jr.: "Chuck" as a young boy snuggling in Santa's lap during the holidays, smiling through a green football helmet a few years later, graduating from Marine boot camp at Parris Island, dressed in a tuxedo, holding hands with his two kids.

Graner, born in 1968, was an avid, if not particularly gifted, athlete as a kid, who played Little League football and baseball. Red volunteered as his coach through much of Graner's youth. By high school Graner was on the track team. He did the pole vault. He ran for president of the student council.

After high school and a couple years of college, Graner joined the Marines in 1988. He served in the first Gulf War. He came home with the panic attacks and insomnia that were common among war veterans, but like many others, he had trouble documenting to the government his exposure to trauma during the war in order to get help. If only he'd had photos, he told his parents. A dozen years later, there were pictures, too many of them.

After marriage (and two kids) and divorce, and stints as a school custodian and a prison guard, Graner joined the Army Reserve in early 2002. He was called to active duty in Iraq in 2003. Graner was assigned to Abu Ghraib, Iraq, as a military policeman with the Army's 372nd Military Police Company. Part of Saddam Hussein's notorious prison at Abu Ghraib, where thousands of political prisoners had been tortured and many executed, had been repurposed by the U.S. military as a holding pen for Iraqi detainees. The detainees were interrogated, often cuffed, clad in orange jump suits and routinely subjected to solitary confinement. Charles Graner and the other guards started taking pictures.

The pictures took America by surprise back in 2004. Not so, the Graners. Graner regularly e-mailed his parents about life at the prison, including the abuse. He described the routine brutality at Abu Ghraib in quotidian language that would have seemed strange unless you knew, as we do now, that the soldiers there were mostly doing what they were told to do by the various authority figures who were issuing orders. Graner e-mailed the photos home months before the same pictures put America on its heels.

"He sent me every picture," Irma said. "I saw the rope. I saw the naked guy." She recalled that Graner "would write home to us about the Other Government Agency," a term for the CIA operatives at the prison, who conducted brutal interrogations, including one in which a detainee died chained to a window in a shower room -- though no one has faced consequences from that agency. "And they had to hide people when the Red Cross came," she said.

"Tonight ended up being the same ole same ole," Graner wrote his parents in an e-mail dated Dec. 12, 2003, four months before the scandal broke. He attached a now-infamous photo of a black dog snarling at a nude detainee cowering outside a cell with his hands on his head. "Inmate tries to break out of cell i find out i punish i bring in dogs i get assaulted dog bites prisoner," Graner wrote. "I think he was more trying to get away from the dogs than really wanting to assault me but he did and he paid."

The Abu Ghraib scandal broke in late April 2004, when CBS' "60 Minutes II" broadcast the horrific images from the prison. While military protocol usually calls for separate chains of command for interrogators and military police, at Abu Ghraib, military police like Graner received their brutal marching orders from military intelligence interrogators and even civilian contractors.

The White House immediately began spinning a version of Abu Ghraib that put all the blame on the lowest ranks. "The practices that took place in that prison are abhorrent and they don't represent America," President Bush said on May 5, 2004, in the wake of the scandal. "They represent the actions of a few people." Bush promised that there would be a "full investigation and justice will be served."

"These terrible acts were perpetrated by a small number of U.S. military," Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld told the Senate Armed Services Committee two days later. Richard Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, blamed "those few who don't uphold our military's values."

It is challenging to summarize the overwhelming mountain of evidence that pins the blame for the prisoner abuse squarely on the upper ranks of the Bush administration rather than the lower ranks of the Army. More than two years before Bush pledged a full investigation of the events at Abu Ghraib, his attorneys at the Department of Justice approved an interrogation regime for Abu Zubaydah, one of the first suspected al-Qaida operatives held by the CIA; it included techniques, like waterboarding, that were more brutal than anything caught on film at Abu Ghraib. By August 2002, the White House had pried a memo out of the Justice Department that said you weren't torturing a prisoner unless the treatment was "equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death."

The White House issued two secret memos over the next two years assuring the CIA that the interrogation techniques, including waterboarding, were legal.

On Dec. 2, 2002, Rumsfeld signed a memo authorizing the use of a panoply of abusive interrogation tactics at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, including stress positions, exploitation of phobias such as a fear of dogs, forced nudity, hooding, isolation and sensory deprivation. Lt. Gen. Randall Schmidt, a military investigator, discussed Rumsfeld's interrogation tactics in a 2005 Army inspector general's report. Schmidt noted, "Just for the lack of a camera, it would sure look like Abu Ghraib."

Myers, the chairman who blamed those "few" soldiers at Abu Ghraib, personally quashed further legal review of the interrogation techniques cited in Rumsfeld's memo, even though officials from the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps all warned they might be illegal.

Rumsfeld's techniques resulted in an unknown number of detainees suffering at the hands of U.S. interrogators, including the well-documented interrogation at Guantánamo in late 2002 and early 2003 of a detainee named Mohamed al-Kahtani. Kahtani received 18- to 20-hour interrogations during 48 of 54 days and among other things, was forced to stand naked in front of a female interrogator and accused of being a homosexual. Interrogators also forced him to wear women's underwear and to perform "dog tricks" on a leash. In a sign that the same techniques later migrated to Iraq, a photograph from Abu Ghraib shows Lynndie England holding a dog leash attached to a naked Iraqi detainee. Graner took the photo.

But if Charles Graner and his parents ever harbored any hope for equal justice, it evaporated during Graner's military court-martial in January 2005 at Fort Hood, Texas. As in the initial internal military investigation, first obtained by Salon, Graner faced a prosecution focused completely and narrowly on the abuses captured on film.

A military judge smothered attempts by Graner's attorneys to dig into the authorization of abuse up the chain of command. Despite private assurances that Graner could leave the courtroom through a side door, he was frog-marched before the press.

"All they wanted to do was crucify him," Irma said. Red told me that it was clear that the administration "needed to protect themselves, and I knew they were going to protect themselves. By prosecuting him they severed the link."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Red and Irma first traveled to Fort Leavenworth to visit their son in February 2005. "It was terrible," Irma recalled.

They stepped through a metal detector into a cold stone building, then into a barren room with tables and chairs where family members can meet with prisoners. Graner was nowhere to be seen. This was because he was held in what Fort Leavenworth calls the "special housing unit."

Red and Irma were led into another, much smaller room with two chairs. "You sit down, there is a metal ledge and a big glass window I don't think a truck could drive through," Red remembered.

A door opened. Graner shuffled in. "He was wearing an orange jumpsuit just like they do there at Abu Ghraib," his father recalled. Graner's legs were shackled together and his cuffed hands chained to a leather belt around his waist. Two guards escorted him in. The guards loosened the straps that kept his arms cinched to his waist so that he could reach the phone with his cuffed hands and talk with his parents on the other side of the glass.

In a recent letter, Graner described what it was like for him during that visit. "You are locked in a room with a guard sitting three to four feet behind you watching and listening to your conversation. You are wearing shackles around your feet and a body cuff around your waist," he wrote. "Your arms are attached to your waist by a tether. You are able to see your family through safety glass and speak with them over a phone. All conversations over the phone are recorded."

Through that phone, Red and Irma heard how their son had been sent into solitary confinement for what seemed like minor infractions. "He left a bar of soap in the shower, in he goes," Irma explained. "He had one too many magazines, in he goes." Graner got out one hour a day for exercise, alone. "He was not allowed a radio. No watch, no calendar. I think they are trying to drive him crazy. It is not going to work," she said. "You try to put on a good face for him. But the first time I had to cry."

The Graners remembered another visit, nearly a year later. Their son was still in solitary. "I asked a head guard if I could give him a hug. He said he'd check," Irma recalled. "He said no. The next day was Christmas."

After each visit, the guards lead Graner out of the tiny room, then subject him to a strip search, despite the glass between him and his parents. It's ridiculous, Irma complained. "There is no way you can touch him or do anything."

After the strip search, the guards take Graner back to his cell. For 29 months over the past four years, that has meant solitary confinement.

Irma frowned at the thought of her son being held for months in solitary confinement without so much as a watch to follow the time. "I feel that he has been tortured every day that he has been in that prison," she said.

I first heard from Graner via letter in early 2006, when he had been in Leavenworth for a year. It was not long after Salon published the Abu Ghraib files, an exhaustive set of photos from the prison and an exclusive exploration of the Army investigation that had led to Graner's prosecution. Salon followed with months of investigative articles exploring the true origins of government-sanctioned prisoner abuse by the military and the CIA.

On March 31, 2007, Salon published an article about Steven Stefanowicz, a contractor at Abu Ghraib known as Big Steve, whom Army investigators identified as a progenitor of abuse but who faced no legal consequences. I first heard back from Graner soon after.

I had obtained a 307-page transcript of an interview that Graner provided to Army investigators in April 2005, detailing exactly what went on in the prison. I mentioned Graner's 307-page statement in that Big Steve article, writing that Graner had been "granted immunity from further prosecution in exchange for his cooperation" with Army investigators.

A month later I received a friendly letter from Graner, with a Fort Leavenworth return address, noting that he had "enjoyed" my work. "I do have a problem with one thing you have reported about me," he added. The Army had threatened him with more jail time if he did not cooperate truthfully with Army investigators. "I would appreciate if you ... would refrain from implying that I made any type of deal with the government in exchange for immunity, etc. in the future." Fair enough.

We've kept in touch and exchanged letters since then. Once, when Graner was out of solitary, he happened to catch me being interviewed on "Democracy Now!" I was noting that no one had been held accountable for systematic torture under the Bush administration. Graner begged to differ. "Hello. I'm right here," he wrote to his parents.

As the evidence accumulated over the years implicating top administration officials for prisoner abuse, and as I corresponded with him, Graner's imprisonment and treatment at the hands of the Army seemed increasingly unfair. In his letters, Graner has discussed so-called Tiger Teams, interrogators arriving from Guantánamo to teach Graner and the others how to abuse detainees. He has also written about the irony of being investigated by the Army's Criminal Investigation Command, which, he says, was already well aware of the abuse at the prison long before the scandal broke.

But mostly we talk about the conditions of his incarceration at Fort Leavenworth, including solitary confinement. In a letter, Graner described a typical day. "Groundhog day starts at 5:15 a.m. when breakfast is served. After that I would do an hour-ish of yoga and go back to bed until 10 a.m. Lunch is served at 10:45," he wrote. "Between 2:45 and 3:45 p.m., I am allowed to go outside and will run between 5-8 miles in a cage (there is an inside cage but rain or shine I would rather be outside). Dinner comes at 4 p.m. At 5:30 the guard will take me to shower," he added. "The times when I am not exercising, I read," though he added that he has to provide his own books because there is no library access during solitary confinement. "Normally, I fall asleep at 1:30 a.m. (hard to sleep with the lights on 24-7)."

Graner described the continuous light as particularly painful and the combined effect of isolation and continuous light as "insane." He wrote that it was like "living in your bathroom for over two years with the lights always on."

The Army has also denied Graner any contact with his second wife, Megan Ambuhl, whom he married while incarcerated. She too had been a guard at Abu Ghraib, and was court-martialed and dismissed from the Army but was never prosecuted. The Army seized letters and prohibited phone calls and visits from March 28, 2005, to Aug. 22, 2007, a total of 920 days.

Graner described the impact that his living conditions were having on him in a Feb. 13, 2008, appeal to an Army clemency board. He was asking for clemency or a commutation of his sentence. "For over a year I was held in a cell exposed to a light, though it may be dimmed, that was on for 24 hours a day," he wrote in a letter that Red and Irma shared with me. "While I worked for Military Intelligence between October - December 2003, one of the alternative interrogation techniques used was to keep a detainee in light 24 hours a day," he remembered. "After three days without darkness, there would be a noticeable change in the detainee's emotional and mental state," he wrote. "I went my first year in confinement without darkness."

Graner told the board that he suffered from sleep disturbances and nightmares. He described himself as occasionally withdrawn, sometimes not speaking "for weeks at a time."

"Having the lights on all of the time was torture for me," he added.

The board denied him clemency. In his most recent letter to me, mailed Nov. 3, the day before the election, and less than three months before the end of the Bush administration, Graner didn't hold out much hope for a change in his situation. "When I first arrived at [prison], both the commandant and the deputy commandant told me that I had embarrassed the Military Police Corps and that because of that I would never receive any type of clemency or parole from them," Graner wrote. "This could have all been talk, but so far all of my co-accused are out of prison. I have received no clemency or parole."

"The unfairness, that's what bothers me the most," said Graner's father, Red. "It is not just that it is scapegoating -- it is that everyone knows it is scapegoating.

"He is in prison and he shouldn't be."

Shares