On Dec. 4, 2006, U.S. Army Pfc. Albert Nelson was killed in Ramadi, Iraq, in an apparent friendly-fire incident. As first described in Salon, interviews with soldiers and a graphic battle video seem to indicate that a U.S. tank shell hit the roof of the building where Nelson was positioned, taking off his left leg. He suffered for half an hour before dying on the way to a military hospital. A subsequent Army investigation, however, blamed Nelson's death on enemy action.

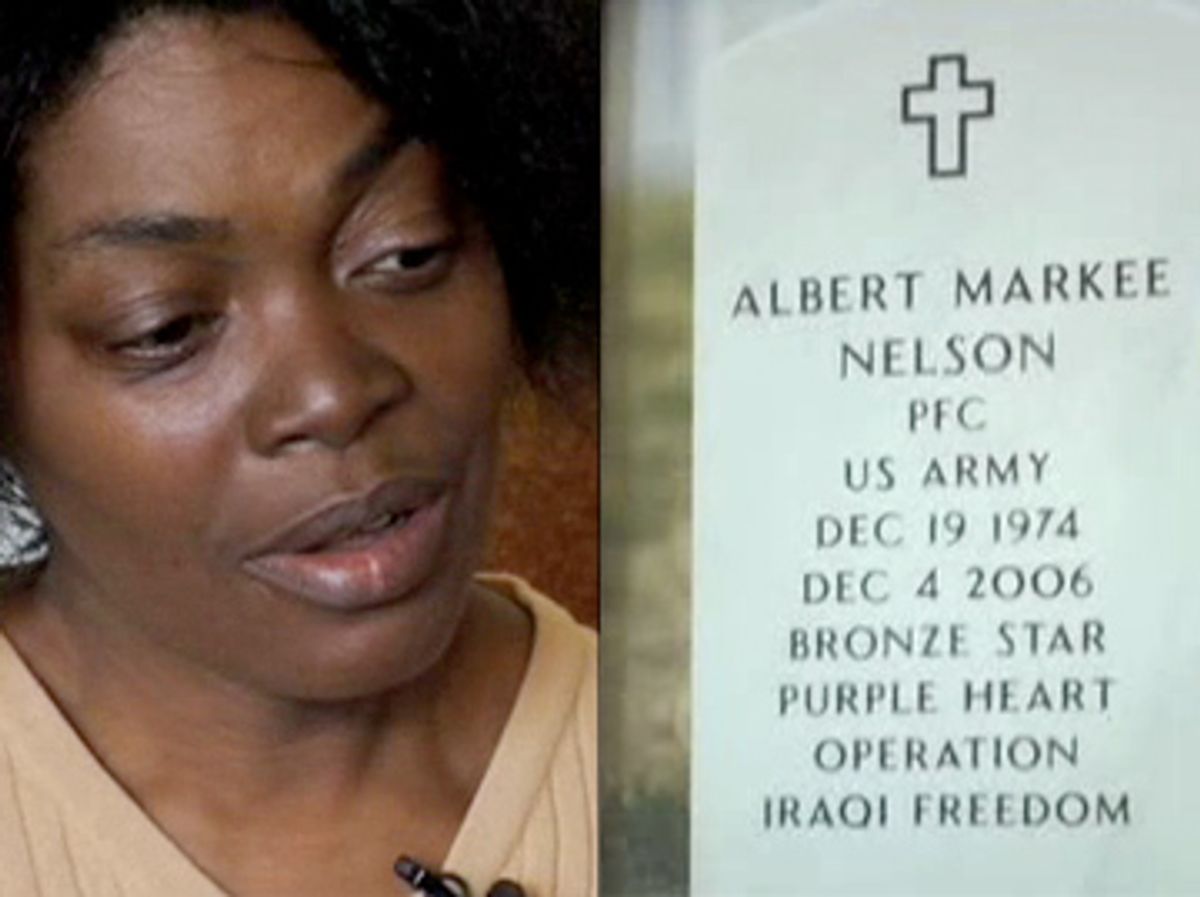

Nelson's mother was not satisfied by the Army's official statement. Jean Feggins had heard that her son's death might have been caused by friendly fire, and she started a letter-writing campaign, demanding more information.

In early 2007, Feggins finally received an in-person briefing, complete with PowerPoint slides, from a high-ranking officer. The officer gave her the official Army version of her son's death, saying he'd been killed by enemy mortars -- a version of events contradicted by the video obtained by Salon. He also assured her that Nelson had died instantly and had not suffered. "When we found him on the roof, he was still in his position," the officer said, "holding his weapon."

Salon has now learned that the Army officer who visited Feggins was Col. Sean MacFarland -- the same officer who conducted the investigation that exonerated the Army. The news comes just as the Associated Press is reporting that the father of the other Army soldier killed in the same incident is demanding answers of his own. Roger Suarez of Carson City, Nev., is asking that Secretary of Defense Robert Gates conduct a new investigation into the circumstances of Pfc. Roger Suarez-Gonzalez's death. His death, like Nelson's, was officially attributed to enemy action.

This fall, nearly two years after Nelson's death, I sat with Feggins on a brown sofa in a small den in the living room of her West Philadelphia home. I had just returned from Fort Carson, Colo., interviewing soldiers who said they watched Nelson and Suarez die when a hail of friendly fire from an American tank blasted their position on the roof.

I held in my hands a DVD recording of the incident in Ramadi, captured by a sergeant's helmet-mounted camera. The video shows the chaotic scene and includes soldiers claiming to have watched the tank fire at the men. The tank shell screamed in from the west, soldiers say, all but obliterating Suarez, sending his head and torso far off the roof to the east.

Feggins' son wasn't so lucky. The tape shows him regaining consciousness and suffering terribly as his buddies struggle to stem his bleeding and keep him calm.

Until I knocked on her door, Feggins had had no idea the tape even existed, but she wanted to see it. "I need to know everything," she told me. "You think I can't handle that? I can handle that. That was my child."

Salon published the article on Oct. 14 along with a copy of the video, with Nelson's image obscured at Feggins' request. The video is painful, Feggins said, but knowing the truth meant a "great weight" had been lifted from her. She wanted the story to be told.

The tape, just over 52 minutes long, shows the men of 2nd Platoon, D Company, 1st Battalion, 9th Infantry, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division hunkered down in a building on the south shore of the Euphrates River in Ramadi. The men are heard and seen pointing to a nearby U.S. tank. After an explosion, the building shakes, and Sgt. Jack Robison, who is wearing the helmet camera, runs upstairs to check on casualties. He finds Nelson on the second floor, missing his leg, being attended by medics. A later search reveals that Suarez has been blown off the roof and killed by the apparent tank shell impact. As the men in the building wait for medical help, several of them refer to being fired on by an American tank.

Although I was able to find Jean Feggins, I was unable to establish contact with Suarez's father, Roger Suarez, before publication of the initial Salon story. But Suarez found his congressman soon after the story appeared. On Monday of this week, Nevada Republican Rep. Dean Heller wrote Defense Secretary Robert Gates, requesting a new investigation into the incident. "Recently video and audio recordings of this incident in Ramadi have been reported by online news services," Heller wrote. "The evidence included in these accounts poses serious questions about how Pfc. Suarez-Gonzalez was killed, and also raises the question as to whether friendly fire may have been involved."

The official Army investigation into Nelson and Suarez's deaths was carried out under the authority of the brigade commander in charge of the tanks in Ramadi that day, Col. MacFarland. I obtained a condensed, heavily redacted 10-page summary of that investigation through the Freedom of Information Act, along with a memo from MacFarland approving the findings. That investigation was completed on Dec. 16, 2006. MacFarland's memo acknowledges that the soldiers who fought with Nelson and Suarez "believed that the tank located to the west was firing at their position." The investigation summary also notes that the video "easily leads to a conclusion" that it was friendly tank fire. Both are wrong, according to MacFarland's memo. "By analyzing shrapnel found at the location, uniform scraps, impact point analysis and audio analysis of the video, it is clear that fratricide was not the cause of death."

Instead, MacFarland's review found that two enemy mortars, one arching high through the sky, the other screeching low across the ground, landed nearly simultaneously on Nelson and Suarez's position on the roof.

The day the initial Salon article on the friendly-fire incident appeared, Oct. 14, MacFarland spoke with me by phone. He said his December 2006 investigation of Nelson and Suarez's death included 170 photographs, dozens of interviews and hundreds of pages of ballistic analysis. He called it "the gold standard of investigations."

On the evening of the day the Salon article ran, three soldiers from Nelson and Suarez's unit were ordered to shred two boxes of documents, mostly records with Nelson or Suarez's name, the soldiers said later. Those soldiers do not know what all they destroyed.

The Army claims that this was a routine shredding of old personnel files, and that while files on Suarez and Nelson were destroyed the night Salon published an article about the men, it was strictly a coincidence.

The Army has not, to date, provided Salon with a full version of the official investigation. I requested a full copy of that material back on July 30, through the Freedom of Information Act. So far, the Army has produced only the heavily redacted, 10-page summary and the short memo from MacFarland approving the findings. Army Freedom of Information Act officials say that so far, they have been unable to locate the full report of the investigation. In an interview, Col. Randy George told me that the documents shredded on Oct. 14, the day the Salon article appeared, were not related to the investigation.

Soon after the Salon article appeared, Feggins received a call from an official with Army Casualty and Mortuary Affairs, apologizing for the fact that Feggins had been told, obviously incorrectly, that her son had died instantly. Feggins seized at the opportunity for more information. She asked the official if the Army files showed the name of the officer who had given her the PowerPoint presentation about her son's death.

Then came the response: "Col. Sean MacFarland," the same officer who oversaw the investigation of her son's death in Iraq.

After the Salon article appeared, officials from mortuary affairs also contacted MacFarland to see why he gave Feggins wrong information when he sat down with her. Those officials called Feggins back with the explanation. MacFarland got confused, they said, between Suarez, who died instantly, and Nelson, who suffered.

MacFarland reiterated the argument in an e-mail to Salon. "The briefing script clearly stated that [Nelson] was mortally wounded and PFC Suarez was killed," MacFarland wrote. "It is possible that the two circumstances of death were momentarily confused during informal discussion before or after the briefing."

Feggins told me she found it amazing that MacFarland could have confused the two men's deaths, but she doesn't have any evidence that proves MacFarland intentionally misled her. (Contrary to what MacFarland told Feggins, however, neither man was found dead at his position with his weapon in his hand. Suarez was dismembered by the explosion and blown off the roof, while Nelson was taken downstairs to await evacuation.) She wonders, however, whether it is just another slippery chapter in an official Army story full of unlikely explanations.

MacFarland, meanwhile, has been promoted. MacFarland got a star pinned on his uniform in an Oct. 25 ceremony at Fort Bliss, Texas, 11 days after Salon published the allegations of the friendly-fire coverup under MacFarland's command. He is now a brigadier general.

MacFarland is something of a hero among some Army officers for his work pacifying Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province, once a hotbed of Iraq's Sunni insurgency. The military peacefully handed over the province to Iraqi control in September 2008. The West Point grad is considered an up-and-comer and a protégé of Gen. David Petraeus, the father of the so-called surge strategy in Iraq and now commander of U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Shares