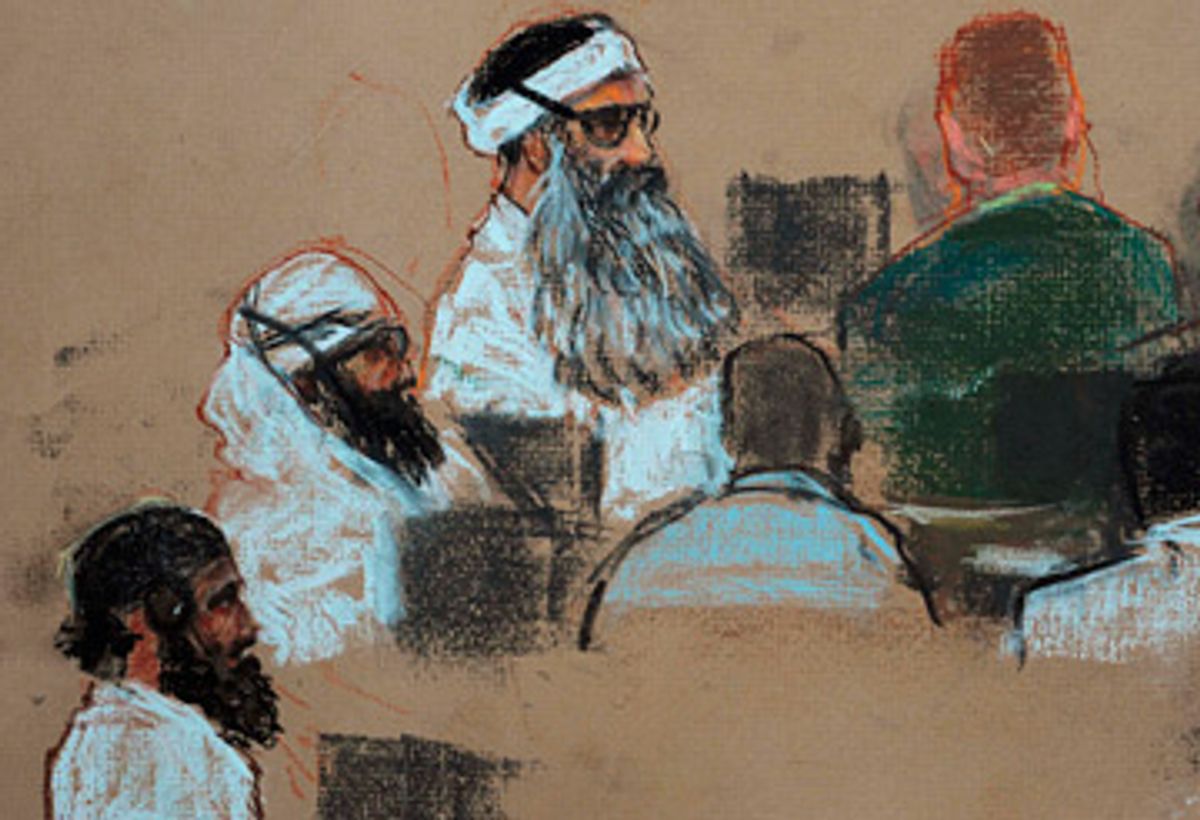

On Monday, the circus known as "Guantánamo justice" devolved once again into chaos, with alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed raising the possibility that he and other prisoners once held by the CIA would plead guilty to involvement in the 9/11 attacks. The anarchic proceedings only served to underscore the makeshift nature of the military tribunals, and to remind the world of the reasons the prison should be closed.

But even as President-elect Obama repeats his oft-made promise to shutter the prison that has so besmirched the nation's reputation, some legal experts, and not just those on the right, are talking about giving him the right to open a new Gitmo here at home. An extraordinary debate is under way about whether Congress should expressly authorize the new president to do what the outgoing president did on his own claimed authority: imprison alleged terrorists without charge or trial.

It may surprise some to learn that in the waning days of the Bush administration, there is an emerging narrative in Washington think-tank circles -- a narrative that shows signs of congealing into "bipartisan consensus" -- that Congress should enact a law that expressly permits such detention. What underlies the consensus is the theory that our criminal justice system is unequal to the task of detaining terrorists in a dangerous world. The impetus for this discussion is the likelihood that an Obama administration will, in fact, move to close Guantánamo, and its urgency is supplied by the claim that among the 250 prisoners still imprisoned there are many who are too dangerous to release, but too difficult to prosecute. Accordingly, the argument goes, unless Congress devises a new legal framework for detaining terrorism suspects for preventive purposes, the closing of Guantánamo means that hordes of terrorists will be released to carry on their war against America.

Proponents of a new detention-without-trial regime contend that there are a sizable number of detainees at Guantánamo whose release would pose an unacceptable risk, but whose prosecution in our traditional criminal justice system would face insurmountable obstacles. For example, Matthew Waxman, who held senior positions in both the State and Defense Departments under President Bush and now teaches at Columbia Law School, states that "criminal prosecutions [of Guantánamo detainees] should be carried out whenever possible," but insists that "the evidence against a particular suspect often can't be presented in open civilian court without compromising intelligence sources and methods," and furthermore, that "the evidence may not be admissible under U.S. criminal law rules." Benjamin Wittes, a Brookings Institution scholar and author of "Law and the Long War," which advocates a new detention regime, is more blunt in explaining why some terrorism suspects cannot be criminally prosecuted: "because they have not committed crimes cognizable under American law, because evidence against them was collected in the rough and tumble of warfare and would be excluded under various evidentiary rules, or because the evidence is tainted by coercion." For those reasons, Wittes contends, Congress must move quickly to enact a law that would authorize the long-term detention without trial of suspected terrorists, following some kind of judicial process to assess the dangerousness of the detainee.

These claims concerning the shortcomings of the traditional criminal justice system can be considered in turn. Is there evidence that the existing system has proven inadequate to the prosecution of dangerous terrorists? Is it true that convictions could not be obtained against these detainees "without compromising intelligence sources and methods"? Finally, is it true that the evidence needed to obtain their convictions might be inadmissible in a U.S. federal court?

Although the debate about these issues has largely been driven by Guantánamo, the detention, interrogation and prosecution of terrorism suspects by the United States did not begin with the Sept. 11 attacks. The United States has captured and successfully prosecuted scores of terrorism suspects, at home and abroad, both before and after Sept. 11, and any serious debate about the adequacy of the criminal justice system to handle these cases must begin not with the abstract concerns of scholars, but with the actual experiences of prosecutors.

Fortunately, much of this work has been done in a comprehensive and authoritative report published by Human Rights First and written by Richard Zabel and James Benjamin, both former federal prosecutors. The report, "In Pursuit of Justice," examines more than a hundred international terrorism cases that were prosecuted in U.S. federal courts, and concludes that those courts are well-equipped to accommodate the government's legitimate national security interests without compromising the fundamental rights of criminal defendants. Federal prosecutors have an imposing array of prosecutorial weapons for targeting suspected terrorists, including statutes that criminalize assault and homicide, the use of weapons of mass destruction, and harboring or concealing terrorists.

Of the many statutes that prosecutors have employed against suspected terrorists, perhaps the most far-reaching are those that criminalize the provision of "material support" to organizations that have engaged in terrorism or have been designated as terrorist organizations. These statutes allow the government to secure convictions without having to show that the defendant actually intended to further terrorism, and indeed without having to show that any specific act of terrorism has taken place or is being planned. Thus, in recent years, defendants have been convicted of material support for attending terrorist training camps, for giving medical aid to injured fighters, and for supplying funds for the humanitarian activities of designated terrorist groups. In fact, the material support laws are so sweeping that they have been criticized for criminalizing conduct that is protected by the First Amendment. (In one pending case in New York, the government is prosecuting a man whose "material support" consisted of rebroadcasting a Hezbollah television station in Brooklyn, N.Y.) But while one can fairly criticize the material support laws for criminalizing too much conduct, it would be difficult to criticize them for criminalizing too little. Given the vast sweep of those laws, it is hard to imagine that Guantánamo holds any substantial number of men who are simultaneously impossible to prosecute and yet too dangerous to release.

The contention that the federal courts are incapable of protecting classified information -- "intelligence sources and methods," in the jargon of national security experts -- is another canard. When classified information is at issue in federal criminal prosecutions, a federal statute -- the Classified Information Procedures Act (CIPA) -- generally permits the government to substitute classified information at trial with an unclassified summary of that information. It is true that CIPA empowers the court to impose sanctions on the government if the substitution of the unclassified summary for the classified information is found to prejudice the defendant, and in theory such sanctions can include the dismissal of the indictment. In practice, however, sanctions are exceedingly rare, and of the hundreds of terrorism cases that have been prosecuted over the last decade, none has been dismissed for reasons relating to classified information. Proponents of new detention authority, including Waxman and Wittes, invoke the threat of exposing "intelligence sources and methods" as a danger inherent to terrorism prosecutions in U.S. courts, but the record of successful prosecutions provides the most effective rebuttal.

The proponents of a new regime are aware of the broad range of existing anti-terrorism statutes, and of the availability of CIPA to guard against disclosure of sensitive national security information. So why do they persist in advocating for additional detention authority for terrorism suspects?

To his credit, Wittes is more candid than many other advocates of expanded detention authority in explicitly revealing a major source of his concern: that the evidence necessary to obtain convictions against some terrorism suspects is "tainted by coercion" and thus inadmissible in U.S. federal courts. In congressional testimony and in a recent Washington Post article, Wittes pointed to Mohamed Al Qahtani, a Guantánamo detainee, as the paradigmatic profile of an individual whose legitimate prosecution may be fatally compromised by coercive treatment, but whose release would pose too great a menace to Americans.

That Wittes would invoke Qahtani in support of his proposal for expanded detention authority is, in a word, astonishing. Qahtani -- who U.S. officials believe may have been the intended "20th hijacker" -- was subjected to perhaps the most meticulous and brutal torture protocol of any Guantánamo detainee: his "interrogation logs" for a 50-day period in 2002 and 2003, leaked to and published by Time magazine, make for harrowing reading. Qahtani was strapped down, injected with fluids, and forced to urinate on himself; he was subjected to prolonged sleep deprivation, often woken in the middle of the night by dripping water or blaring pop music; his head and beard were forcibly shaved; he was left naked in a frigid room and forced to stand for prolonged periods; he was sexually humiliated by female interrogators; he was menaced by dogs and was himself led around on a leash and forced to bark like one. An FBI agent who witnessed some of this abuse wrote that Qahtani had been "subjected to intense isolation for over three months" and "was evidencing behavior consistent with extreme psychological trauma (talking to nonexistent people, reporting hearing voices, crouching in a cell covered with a sheet for hours on end)."

In short, Qahtani was a victim of what the United States once undoubtedly would have prosecuted as war crimes -- the distinction being that in this instance, those crimes were authorized by the secretary of defense and implemented by Guantánamo's commanding general. In Wittes' sterile formulation, the systematic brutality perpetrated against Qahtani is sanitized as "coercion" -- and its significance is that it may complicate any future prosecution of Qahtani, not that it supplies a basis for the prosecution of his torturers.

Assuming, as Wittes does, that there is no evidence of Qahtani's involvement in criminal conduct that is untainted by the government's criminal conduct toward him -- something that is by no means clear -- his case squarely presents the question whether we are prepared to change our laws in order to avoid the consequences of the Bush administration's criminal embrace of torture. Wittes' argument can be summarized succinctly as follows: 1) We brutally tortured Qahtani; 2) thus, our evidence of his criminality is "tainted," rendering his prosecution impracticable; 3) therefore, we must amend our laws to allow for Qahtani's indefinite detention without charge or trial. Thus does the Bush administration's catastrophic insistence that an entirely new legal regime was necessary become, in the hands of a liberal scholar, a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The leading proposals for new detention authority differ in their details, but they suffer from similar flaws. For one thing, any statute that permits detention until the end of the war on terror, or even the end of the conflict with al-Qaida, will amount to an authority to detain indefinitely. This is not because al-Qaida is a more formidable foe than the United States has faced in previous conflicts, but because al-Qaida is a loosely organized group capable of inspiring attacks without formally directing them. As some terrorism experts have observed, al-Qaida may be more a banner than an entity, and it is likely that even decapitating its leadership would not eliminate its capacity to do harm. Thus, it is not simply that we don't know when a "war" with al-Qaida might end; it's that we don't even know how.

But perhaps the most salient flaw in the current crop of detention proposals is that they are solutions in search of a problem. The class of people who cannot be prosecuted but are too dangerous to let go is either very small or nonexistent. To the extent that it exists at all, it is a class that was created by the administration's torture policies. To build a system of detention without trial in order to accommodate those torture policies would be a legal and moral catastrophe, a mistake of historic proportions.

How an Obama administration chooses to tackle these issues will determine, in large part, the legal legacy of the last eight years. Even the clearest renunciation of torture will be an empty gesture if we simultaneously construct a new detention regime meant to permit prosecutors to rely on torture's fruits. That our justice system prohibits the imprisonment of human beings on the basis of evidence that was beaten, burned, frozen or drowned out of them is evidence of its strength, not its weakness. It is why we call it a "justice system" in the first place.

It is possible, though unlikely, that one consequence of the Bush administration's criminal embrace of torture is that the United States will be compelled to release an individual who might otherwise have been prosecutable for terrorism. Were this to occur, it would not be the first time that our commitment to the rule of law has required that we let a potentially dangerous person walk free. We can accept this risk as an inherent cost of freedom, or we can diminish that freedom in a misguided -- and shortsighted -- attempt to reduce that risk. The choice we make will not determine the nation's survival. It will, however, shape its identity.

Shares