"You should interview Steven Chu," the scientist at the Joint Genome Institute in Walnut Creek, Calif., told me. "He already has one Nobel Prize. He wants to get a second one for solving the energy crisis."

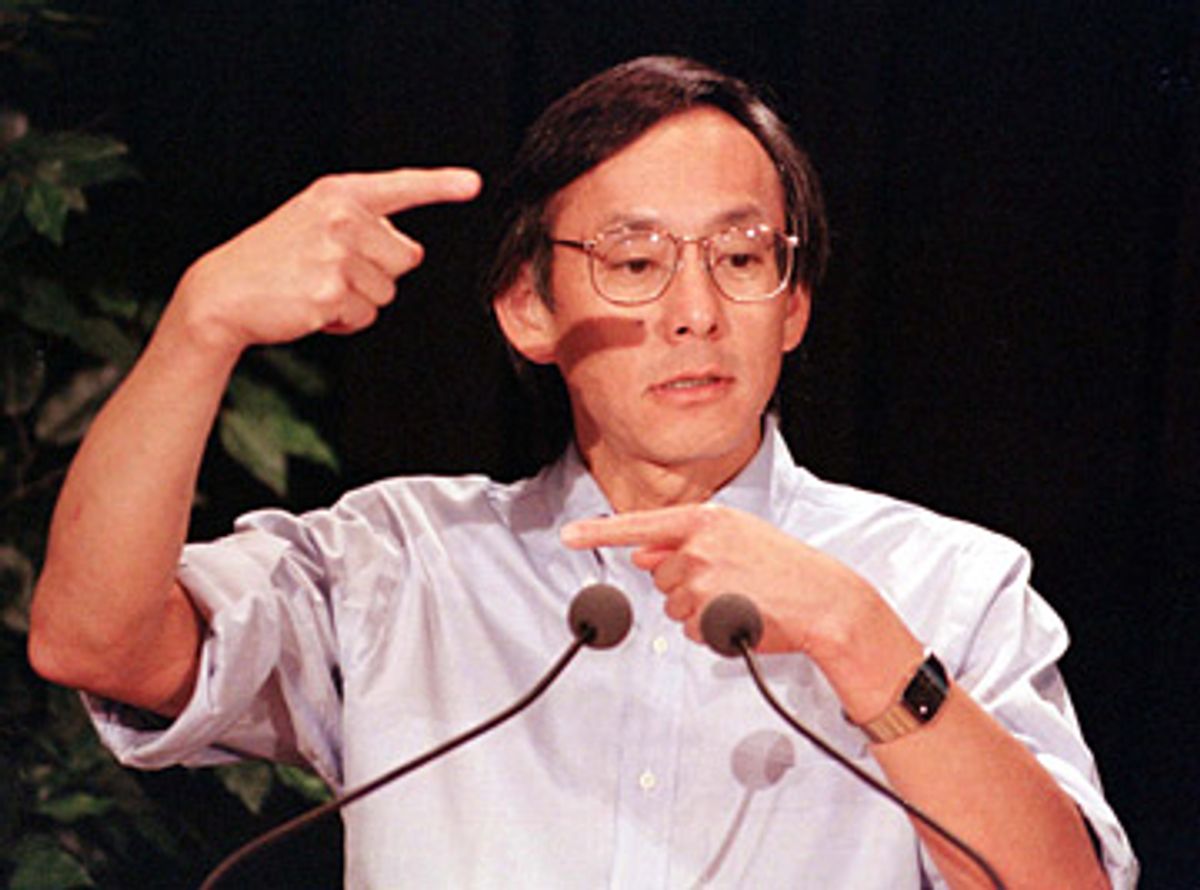

That was two years ago, and I sorely regret not following through and landing an interview with Chu, a physicist who has dedicated his post-Nobel Prize career to the development of alternative sources of energy. Because as Barack Obama's nominee for secretary of energy, Steven Chu is going to get a chance to make his dreams come true, with the full backing of the U.S. government.

Since 2004, Chu has served as the director of the University of California-managed Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, spearheading, among other things, a massive research effort in solar power. To get a sense of the man's interests, here's the second sentence of his bio at the LBNL Web site. (LBNL, located in Berkeley, Calif., should be distinguished from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which does weapons research for the U.S. government.)

Chu, an early advocate for finding scientific solutions to climate change, has guided Berkeley Lab on a new mission to become the world leader in alternative and renewable energy research, particularly the development of carbon-neutral sources of energy.

Environmentalists and climate change activists are understandably delighted. Consider this: For eight years the United States has boasted an Energy Department that for all intents and purposes was a subsidiary of the U.S. oil industry. Now, should he be confirmed, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist who specializes in climate change and renewable energy and already knows how to run a decent-size bureaucracy is going to be in charge of realizing Obama's bold promises to lead the United States toward an energy-sustainable future. Symbolically speaking, one would be hard put to draw a sharper contrast between the Bush and Obama eras than what is achieved by this single appointment.

That said, Steven Chu is no stranger to Big Oil. He was instrumental in helping U.C. Berkeley land one of the biggest corporate bonanzas ever -- $500 million from British Petroleum to establish the Energy Biosciences Institute, an ambitious joint venture that has been controversial from the get-go at Berkeley because of its plans to use oil money to do research and development into energy crops and other biofuel wizardry.

And, as I noted after seeing him talk in early 2007 at a symposium titled "Domestic Bioenergy: Weaning Ourselves From Foreign Oil Addiction," held at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he is on record as being a bit hyperbolic as to the potential of biofuels.

There is enough marginal, unused agricultural land in the United States to generate the biomass necessary to reach the one-third goal [of displacing annual American gasoline consumption with biofuels,] without displacing food production, said Steven Chu, the Nobel physics prize winner who runs the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. And the laws of thermodynamics won't need to be broken -- there is more than enough energy hitting the earth every day as sunlight to supply all of humanity's energy needs.

You can find plenty of scientists who will dispute such assertions, right down the hill from Chu's offices above the campus of U.C. Berkeley. There's also no question that the political climate for biofuels has changed drastically since February 2007.

But for those who bemoaned the Bush administration's steadfast opposition to taking action on climate change and its criminal abuse of the scientific method, there's reason to cheer. The sight of a scientist whose professed goal is to combat climate change and wean the U.S. from dependence on oil put in charge of the U.S. Department of Energy is welcome indeed. You could almost call it change.

Shares