It's hard not to marvel at the extremity of some pet lovers' devotion, whether it's preparing a special raw meat diet each day or paying skyrocketing veterinary bills. But whatever form the expression of that affection may take, the feeling itself isn't strange at all, according to Meg Daley Olmert, author of "Made for Each Other: The Biology of the Human-Animal Bond."

Daley Olmert had written documentaries for the likes of National Geographic Explorer and PBS's "The Living Edens" when she set out to explore relationships between humans and animals. Despite her lack of formal scientific training, she was even able to join a research team studying the neurobiology of social bonding at the University of Maryland. What she learned is that there is a physiological basis to the profound attachment so many of us feel for our dogs and cats; the same hormone, oxytocin, that bonds a new mother and infant is at work in the relationships between today's animal lovers and their four-legged friends.

In "Made for Each Other," Daley Olmert outlines what's known about the history of how humans and the mammals closest to them co-evolved, while exploring the emerging medical research that suggests caring for an animal can actually make us physically healthier. And she speculates about why so many Americans have welcomed pets not only into their homes and even beds in recent decades, but into the very hearts of their families.

While many cat or dog people feel self-conscious or embarrassed about the intensity of their relationships with their animals, Daley Olmert offers a spirited defense of those feelings, suggesting that the capacity to bond with an animal deeply is nothing to feel ashamed about. It is even rooted deeply in our natures.

Salon spoke with Daley Olmert by phone from her home on the eastern shore of Maryland, where she lives with her husband and their two cats, Boo and Coco, who have even been known to go kayaking with them.

Just how central to many Americans' lives are pets now?

Congress passed a bill after Hurricane Katrina because so many people remained behind because they would not leave their animals. People died because the state law of Louisiana did not account for evacuating animals.

There is now a law that says all state evacuation emergency plans have got to have a contingency for pets, because they did a survey after Katrina, and the majority of pet owners said, "I'm not leaving without my pets."

When I pat my cat, what is happening between us, biologically speaking?

Touch releases oxytocin in humans and animals. Oxytocin is one of the most powerful hormones that the body makes. This is a chemical that is responsible for social bonding.

When you pat your cat, you should be getting a release of oxytocin, as should your cat, too, that slows your heart rate down, lowers your stress response. You feel this warmth and this attachment, as does the cat. So you're getting an emotional and a physiological anti-stress response. It's a wonderful renewable system.

What are the other relationships in which we see oxytocin in play?

It was first discovered as being a hormone that causes labor contractions in women and breast-milk release. Labor and lactation are its best-known bodily functions. About 15 years ago is when scientists started saying, "Hey, you know, oxytocin isn't just made in the breast and in the uterus, it's made in the brain." In the brain it connects with every major brain center that controls emotional behavior. It has profound behavioral effects as well as anti-stress effects.

It is released through every sense. In mothers, the sight, smell, sound and touch of your baby releases it in you. A study that has just been done in Japan shows that even eye contact with your dog raises oxytocin in you. In humans, it is well known that oxytocin is released during sex, hugging, massage, all sorts of nurturing, physical contact.

When a dog owner says, "My dog can read my mind. He just knows when I'm going to take him for a walk," what is really going on?

Much of our communication is not verbal. It's about body posture, tone of voice and the way we look that animals can read perfectly. They have been our captive audience for thousands and thousands of years. They've had to learn to read the nonverbal aspects of our language, which are so telling.

There's a phenomenon known as ideomotor action. If you put electrodes on a person's neck, and tell them: "Imagine looking up at the Eiffel Tower," you will see that the muscles that would actually lift their head and look up at an Eiffel Tower, were it there, are activated.

Animals are muscle readers of the highest order. It is highly possible, and in fact they've proved it with horses, and the Clever Hans horse in Germany, that animals can read those tiny micro-movements. It tells them a world of information long before we're clued in that we're actually thinking it.

What is known about the emotional history of humans and animals?

We have had very intimate relationships with animals: lived with them, slept with them, cared for them, delivered their babies, bottle fed them when the mothers couldn't. These things humans don't escape from emotionally untouched. They definitely create bonds.

Basically, domestication is a form of a case of mistaken identity. We began to see them as ours and they began to see us as them. The reason I can milk a cow is because the cow thinks that I am its baby. The term animal husbandry is not a misnomer.

Now, it is true that farmers slaughter their animals, and there is a pragmatic aspect to it, but if you look at stories of nomadic herders and people who still live in these very tight, bonded relationships with animals, they consider these animals kin, even if they end up slaughtering them sometimes.

Living with animals has always had an emotional bang to it that people tend to not think about. As soon as we have written accounts, people talk about these fantastic emotional relationships with animals. The Egyptians are famous for it. They loved their animals, and they revered them. They were our gods before they were just fodder.

You wrote that Egyptian families used to shave off their eyebrows in mourning when their cats died!

Believe me, when my cats die I'm doing it.

And that some women have been known to actually nurse other mammals. What are the possible implications of that?

It's not uncommon at all in tribal cultures for women to suckle young animals. Very often in societies where pups are suckled or piglets are suckled, those animals are spared from becoming dinner, because the bonds do form.

Now we know that when a woman suckles her baby, huge amounts of oxytocin are released in the mother and how that bonds her to that baby. You have to rethink the implication of what it meant when perhaps a prehistoric cavewoman might have picked up a wolf pup and suckled it.

It would have unleashed oxytocin's tremendous bonding powers in her. And, of course, the pup's crying released the first bit of oxytocin, and the fact that it looks like a baby. That's what made her pick it up and bring it to her breast to begin with. This chemical, which is released through nurturing touch and breast feeding, could have jump-started domestication.

So, you're speculating it could have played a role in the changing relationship between people and wolves that evolved into the relationship between people and dogs?

Yes. One of the things about oxytocin is that it's a taming molecule. It inhibits fight/flight, which is what makes animals wild. Oxytocin reaches out to all these other brain areas, like the dopamine receptors, the serotonin receptors, these powerful brain centers. It coordinates a shutdown of this antisocial behavior called fight/flight and replaces it with a chemistry that promotes curiosity over paranoia. In that mind-set is when humans and animals can approach each other.

When you think about it, how did wild animals ever become tame? It's a change in the nervous system. Then you have to ask: What changed the nervous system? This newly emerging physiology points to oxytocin being one of the central components of this major shift that happened in humans and animals promoting more cooperative behaviors.

So, humans also were domesticated.

We often talk about how we've changed animals in their relationships with us, but how do you think that domestication changed us?

Early humans were prey animals, basically. We were the ones that were hiding behind the rocks, looking out on the savannah. We were the ones that were going to get eaten. We were slow, we were weak. Our physiology had to have been dominated by fight/flight just like any good herbivore out there being stared down by a big cat or dog. Something in us shifted and emboldened us to start to approach the same animals that we once feared and ran from.

What do you think is going on culturally now that pets are so popular in the United States?

My theory is that we're suffering from oxytocin deprivation.

We walked off the farm in the past hundred years and broke a link to nature and animals that was 10,000 years old. If you follow my premise that the ever-increasing contact with animals was able through touch and sight and smell to really boost this chemical bond between humans and animals, then what happens when you, in just 50 years, go from 33 percent of Americans living on farms to the Census Bureau just stopping even counting because there are so few people left percentage-wise in America living on farms? That's a huge and sudden divorce from the animals and from the chemical milieus that they created.

And what would happen if this same chemistry of bonding was also the chemistry of anti-stress? You would find that people would be flipping out, and they are. Children are more depressed, they're more anxious than ever before. A huge study showed that children born after 1955 are three times more likely to suffer depression than their grandparents were, grandparents who had lived through world wars.

What you see is that the Industrial Revolution causes this great flight from farms, and we are stripped bare of the land, the whole tactile nature thing, not just the animals. My feeling is that people are grasping intuitively at their animals, desperately trying to create this homeostatic correction.

All this sort of attention that people are lavishing on their pets these days is symptomatic of the need for oxytocin?

People are also desperately isolated from each other, and not just from the land. We are a lonely people now, and getting lonelier in this disruption from leaving the farm.

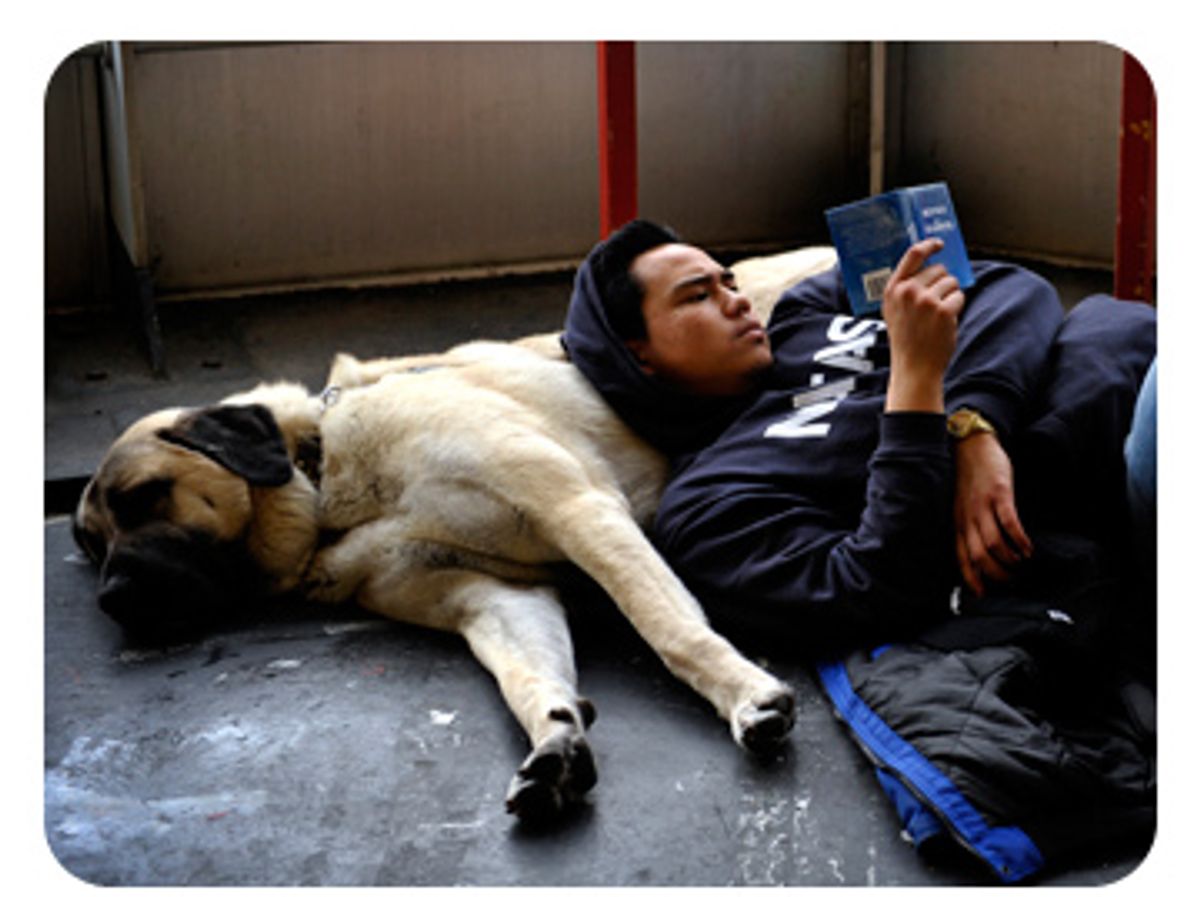

We're back to human migration, the way of life that we decided was not adaptive 10,000 years ago, when we settled down. People are moving constantly, and it's very difficult to maintain social relationships. And so what you get is people desperate to establish a strong social bond. It's very difficult to do with humans. It's much easier to do with animals. We're surrounded by people, but touched by so few, and so you come home to your empty apartment, and there is your pet, and it is wonderful.

Seventy-eight percent of elderly male pet owners and 67 percent of female elderly pet owners said that their pets were their only friend. Just like people self-medicate with alcohol and drugs, in a way they're self-medicating with their pets.

Is there evidence that pets actually are good medicine?

There are a couple of terrific studies. There need to be more. In a very big study at the Minnesota Stroke Institute, cat owners had a 30 percent reduced risk of heart attack.

There have been several studies that showed dog ownership significantly increases the ability of somebody to survive during that crucial first year after a heart attack, and it's not because they go for walks. Other studies show that it isn't the exercise, it's the companionship.

Just having a pet in a room when you're doing a mental stress test has been found to lower the subject's heart rate, blood pressure and stress-hormone levels better than having their spouse in the room.

Given that pets give us all these benefits, why do you think that we have the persistent stereotype of the pathetic cat lady, who is alone with her cats in her house? What you're saying is that she should have cats, it's probably good for her.

I hope that she won't be seen as quite so pathetic in the future. Or, that people will realize that she's just self-medicating. Go have a drink. That's what we do.

But I don't want people to think that you can just have a dog and you can chain it up in the backyard, and you're going to get fabulous love and attention from it, and all the physical and therapeutic rewards, as well. You won't.

It's very important to realize that if you want the greatest quality of relationship with your pet, as well as the best therapeutic value from it, it all depends on the quality of the attention you are willing to devote to the animal. This isn't about the dog in the pen in the backyard that nobody ever talks to and you take hunting twice a year.

So it's the intimacy of the relationship?

Yes, it's the intimacy. And given the state of affairs in the world right now, we may not be getting healthcare any time soon, but you better figure out how you're going to handle your stress.

Shares