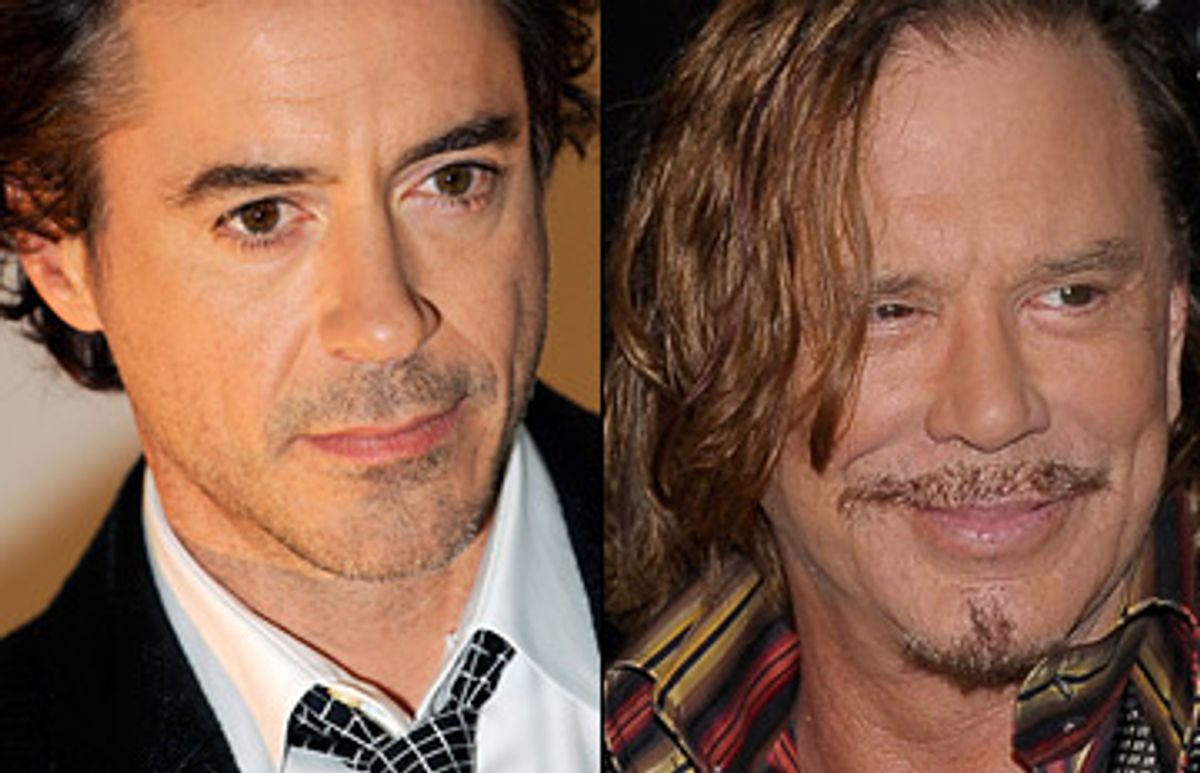

If, as Pauline Kael once wrote, there must be a separate God for movies, there also ought to be one who guards over actor's faces -- not to protect them from aging (if a God of movies is anything like the regular everyday God, he has no interest in stopping the clock), but to oversee, with kindness and sensitivity, the changes that inevitably come with the passing of time, plastic surgery or no. When an actor disappears for a period of time, things happen to that face, sometimes making it seem as if the Face God's attention has been focused elsewhere. For long stretches over the past 20 years, Mickey Rourke and Robert Downey Jr. -- both of whom are in the running for an Academy Award on Sunday, Rourke for his star turn in Darren Aronofsky's "The Wrestler," Downey for his supporting role in Ben Stiller's comedy "Tropic Thunder" -- were absent, or at least sporadically absent, from the movie landscape. Now the two of them are back, playing their respective roles in the sort of comeback story everyone loves. But even beyond the basic appeal of that narrative, their stories tell us something about the faces of actors and what they mean to us, as they get older and as we get older, too. One of these two faces is still conventionally handsome; the other, not so much. But both are faces that have been written on, and together they're a visual treatise on what it means for an actor not just to work with the face he's got, but to live with it.

To look at the faces of Mickey Rourke and Robert Downey Jr. in the movies they made in the early days of their careers -- to note, for instance, the vulnerable-bullshitter quality of Downey's earnest Boy Scout eyes in James Toback's "The Pick-Up Artist" (1987), or the way Rourke's shaggy pompadour in Barry Levinson's 1982 "Diner" accentuates the already-perfect heart shape of his face -- is to see youthful beauty in all its formative, naked glory. These are the faces of actors who haven't yet made their big mistakes, although those younger faces aren't blank pages by any means. Both Rourke and Downey were hailed, early on, as being among the best actors of their era, for good reason: Both had the kind of intuitive, unself-conscious approach that's one of the hallmarks of great American acting. And even if their casual naturalism didn't come straight out of Method acting in the strict sense, it could still be traced easily and directly to James Dean and Montgomery Clift, actors who had earlier explored the dark, resonant tension -- and the ever-elastic connection -- between masculinity and vulnerability.

And then, before we'd even had time to reckon with their astonishing capabilities, both Rourke and Downey more or less vanished -- maybe not as dramatically (or, thank goodness, as permanently) as Dean and Clift had, but they were gone just the same. When Rourke appeared in Lawrence Kasdan's "Body Heat," in 1981, everyone who saw the performance was left asking a single question: Who is this guy? Within 10 years -- and after numerous well-received performances in pictures like "Diner" and "The Pope of Greenwich Village" (1984) -- Rourke, after alienating numerous filmmakers and colleagues with his unprofessional and irresponsible party-boy behavior, had retreated (if that's the right word, and it probably isn't) into the world of professional boxing. And Downey, who had shown such startling promise in movies like "Less Than Zero" (1987) and who went on to give an extraordinarily mature and moving performance in the 1992 film "Chaplin," did something more unsettling than simply disappearing: He began to self-destruct before our eyes. From 1996 to 2003, he was incarcerated on and off on various drug-related charges and seemed to be stuck in the revolving door of rehab. During that time, Downey never completely stopped working. In between stints in jail and rehab, he'd make appearances on "Ally McBeal" and in pictures like the 2000 movie "Wonder Boys." Although neither his skills nor his looks seemed significantly diminished during that time, the next thing you'd know, his name would be in the entertainment-news headlines again, sometimes accompanied by a picture of a disoriented, spent-looking face you'd rather not look at. For a time, it looked as if we'd never get Downey back.

Actors do, for better or worse, belong to us: We're proprietary and protective of them, although we can just as easily turn on them, dumping our stock in them once we've deemed it worthless. As Frank Langella, another Oscar nominee this year for his sure-footed performance in "Frost/Nixon" (and something of a comeback maker himself, although I'd argue that his turn in 2007's "Starting Out in the Evening," as a once-great writer who is both flattered and rattled by the attentions of a young student, is a more resonant and moving performance than the one he's being honored for), wrote in a 1990 essay in the Guardian about the actor's life: "Some basic truths about us, some fundamentals: married, single, divorced, straight, gay, rich, broke, breaking in or holding on, the morning after Oscar, Tony or Emmy, or struggling along without recognition; whether we are newcomers, superstars, an enduring light, a flash in the pan, a has-been or a comeback king, from low self-esteem to insufferable arrogance -- we are the see-saw kids. Kids who hold on tight and wait, wait for the call, the audition, the part, the review -- and then we do it again. Those are the ground rules. You accept them if you are an actor. And you accept the demons."

But I doubt there are many people who wanted to see either Rourke or Downey ultimately consumed by their demons, which is why it's so gratifying to have their faces back -- older, a bit misshapen perhaps, but at least alive. This year Downey gave us two very different performances, and his un-nominated turn as weapons-manufacturer-turned-superhero Tony Stark, in Jon Favreau's "Iron Man," is the more soulful of the two. Iron Man is a self-made hero (he hasn't been bitten by any radioactive spiders, for example), which is what makes the role perfect for Downey. It's satisfying to see him, so down and out a few years back, come back as a subtly defiant reinvention of his former self.

But that doesn't make Downey's performance in "Tropic Thunder" -- as Kirk Lazarus, an arrogant and insecure Australian actor who's so devoted to his craft (or possibly so hungry for an award) that he undergoes a "pigmentation-alteration procedure" to play a black man -- any less worthy, or any less pleasurable to watch. If Downey's Iron Man is a guy who knows what it means to turn his life around, his Kirk Lazarus is a guy who's willing to turn his life around -- to the point of changing the color of his skin -- for his art. The performance is a joyous, disreputable shout: Lazarus renders an unforgettable speech that works as a brilliant piece of criticism on "Rain Man"-style acting (the now notorious "full retard" speech). And the fact that Downey plays the whole movie in blackface is less a statement about racial identity than a jab at actors' egos. Lazarus is driven by hubris. If he can get ahead by making himself black, he'll do it in a heartbeat. And so seeing Downey's face -- still handsome, even if its contours are more careworn than they were 20 years ago -- in a different color becomes a measure of the lengths actors will go to in order to avoid being themselves. In the line of duty, actors become so many people, they often don't know who they really are.

Downey himself has pointed out, in recent interviews, the irony that he's receiving an Academy Award nomination (his second, the first being his nod for "Chaplin") for a performance that satirizes the way actors crave awards in the first place. Rourke's nomination, on the other hand, is less ironic and more poetic in the sense that it's for a performance that almost didn't happen. Aronofsky had always wanted Rourke for "The Wrestler" -- on the condition that Rourke needed to behave himself and refrain from any of the shenanigans that had previously derailed his career -- but the movie's financiers wanted Nicolas Cage, a bigger and more reliable star. When Cage left the project, Rourke was brought back in.

It's impossible to imagine the movie without him. "The Wrestler" is a sturdy, satisfying, old-fashioned comeback story, one that is, in places, overly programmed. But Rourke's performance, as Randy "The Ram" Robinson, a washed-up, beaten-down '80s wrestling star who can't resist trying for a comeback, is so raw that it defies the somewhat facile nature of the movie around it. Rourke hasn't been wholly absent from the movie landscape of late: After quitting boxing in the mid-1990s, he began appearing in a string of movies, giving solid performances in pictures like Francis Ford Coppola's "The Rainmaker" (1997). And from this vantage point, his performance in Robert Rodriguez' sick, twisted and glorious "Sin City" looks like something of a dry run for his portrayal of Randy "The Ram": In that movie, he played Marv, a hulking, square-jawed, sad-eyed loner who sets out to avenge the death of a hooker, one of the few people who's been genuinely kind to him.

That's the kind of roughed-up softie that Rourke now seems to have been born to play. As Randy, he's muscular and robust-looking, but his invincibility is only an illusion. We see Randy slammed with staple guns and crowned with plate-glass windows, all in the name of fun -- and yet, without complaining or wincing, somehow Rourke's Randy lets us know that it all hurts like hell, inside and out.

Part of what makes Rourke's performance so wonderful is the delicacy of his gestures -- the way Randy ever-so-carefully places his hearing aid on the nightstand before turning in, or gingerly wraps up rows of salami slices at his day job at a supermarket deli counter. (If you've seen pictures of Rourke holding his beloved chihuahua, Loki, who passed away a few days ago, you see yet more evidence of that gentle-giant quality: He holds the dog in his beefy hands as if he were cradling a precious Staffordshire figurine.)

But Rourke's face in "The Wrestler" is, in the end, the thing you can't forget. Depending on what you read and where you read it, Rourke has both insisted he's had no plastic surgery to speak of and claimed he's the victim of bad plastic surgery, undertaken to correct damage sustained during his stint as a boxer. But the "Has he or hasn't he" question is irrelevant. There's still so much beauty -- albeit the ravaged kind -- in that meaty mug that going back to look at Rourke's '80s performances isn't as painful as it might be.

Rourke's features are now puffier and less refined, although there's still something mischievously delicate about them, maybe because his smile still has that cupid's bow curve. As Barry Levinson recently said about the young Rourke in an Entertainment Weekly profile on the actor, "There was something about him where you couldn't take your eyes off of him. He was this flashy guy, tough, but audiences responded to the sensitivity under it all. I think that's the side Mickey would like to hide. And his trying to hide it makes it even more fascinating."

Rourke now has a face that bears little resemblance to that earlier one. But if this new face has presented him with some challenges (he can never again be the conventionally good-looking leading man), maybe it's also opened up new possibilities. Now he has the option of hiding his sensitivity in plain sight. There's a chance that Rourke may appear with Downey in the upcoming "Iron Man 2," and even if the deal falls through, it's intriguing to contemplate the idea of seeing these two actors working together. The face you get as you age may not be the one you hoped for. But one of the core skills of being an actor is the ability to work with what you've got, and both Downey and Rourke still have plenty left to work with. In an actor's world, there are always younger actors, with younger faces, coming up quickly to take your place. But the face that's been earned is beautiful by itself, even when it's not such a pretty sight.

Shares