In the age of Facebook, do we really need pop music to reflect the thousand and one shades of teenage -- or post-teenage -- loneliness and jubilation? Why seek connection via "In My Room" or "He's So Fine" when we can so easily tell the world about our feelings du jour, or at least our feelings of the moment, by changing our status message? After all, it would take only a few seconds to read an update like "Brian Wilson has retreated to his safe place, thank you very much" -- far more efficient than actually listening to a three-minute song.

Yet even in the age of seemingly disposable emotions, pop music endures as a means of connection, as a way of packing the immediacy of feeling into something lasting and pleasurable. Which is why the scrappy cheerfulness of Lily Allen, on her new "It's Not Me, It's You," feels like part of a continuum instead of just a momentary blip on the pop-music radar screen.

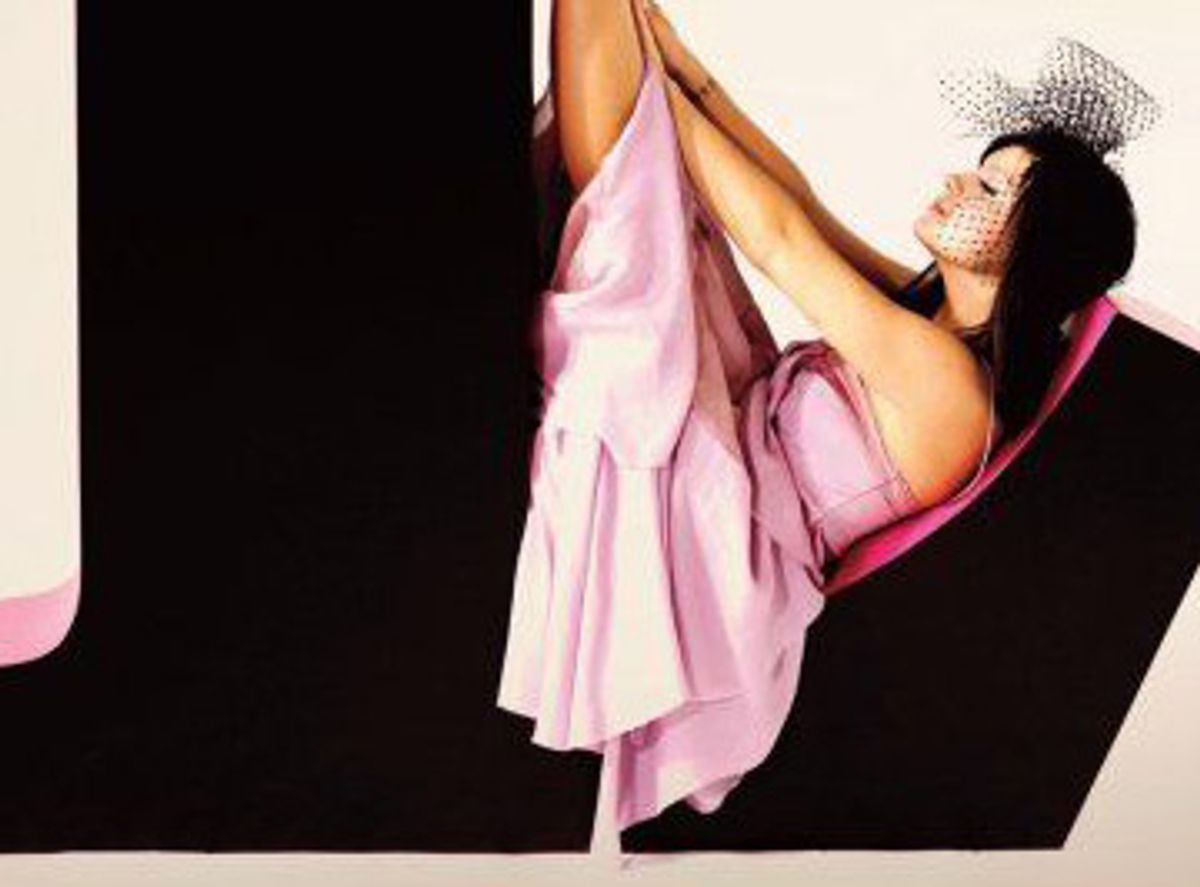

Allen's 2006 debut "Alright, Still" had a disreputably gleeful sound, a sense of spontaneity that suggested a street urchin having a joyride on a stolen minibike. "It's Not Me, It's You" is a more mature record, even though maturity may not be what we want from Allen: That pink tulle party dress of a voice is part of her appeal; who knows what we'd be left with if she were ever to grow out of it?

But even if Allen's voice sounds a little more adult here (in places it resembles that of St. Etienne's Sarah Cracknell), and if the songs -- all written by Allen and Greg Kurstin -- come off as more polished and less delightfully off-the-cuff, Allen's chief concerns on "It's Not Me, It's You" haven't changed all that much. She's alternately giving the kiss-off to lousy boyfriends or tentatively saying "hello" to potentially good ones, perennial pop subjects if ever there were any.

Elsewhere, she ventures into more grown-up territory, defending her right to have good sex, or outlining fears that she'll be consumed by her own celebrity, or offering an olive branch to an absentee dad who, she realizes, isn't such a bad guy after all. But the problems Allen focuses on here don't yet fall into the dull, needlessly complicated adult sort. She's not done with the flirty Sandra Dee dresses or the purloined minibike just yet, even if, as inevitably must happen even in the Neverland of pop stars, she's beginning to see their limitations.

That means Allen is, thankfully, still confessional and open, possibly to the point of oversharing -- although oversharing is probably what gives good pop music its immediacy and its intimacy in the first place. "There's just one thing that's getting in the way/ When we go up to bed, it's just no good," Allen sings on "Not Fair," in a voice that's more accusatory than plaintive. As we get further into the song, we learn that she's giving more than she's getting, as she so explicitly tells us with the lines "Oh I lie here in the wet patch/ in the middle of the bed/ I'm feeling pretty damn hard done by/ I spent ages giving head."

And what, she asks us indignantly, does she have to show for it? The lyrics by themselves come off as vaguely unreasonable, a little tantrum-like -- but that's precisely the idea. "Not Fair" (even its title conjures the sound of a rampaging teenager slamming her bedroom door) is all about knowing what you want and still finding you're unable to get it. What else is there to say but "WTF?" which is exactly what Allen does here. The song, with its giddyap neo-country rhythms, is half Buck Owens, half Pet Shop Boys ("It's Not Me, It's You," produced by Kurstin, is almost wholly and unapologetically nonacoustic), and Allen is the cranky cowgirl in charge of the cattle drive. If a man can't give her what she wants, she tips her hat and moves on, but it's not her style to be laconic: "I think you're really mean," she repeats three times in succession, just to make sure she gets the message across. Is she being childish, unrealistic in her expectations? Of course. But the point of "Not Fair" is that desire itself is an unreasonable beast. Why shouldn't we want to try to control it? At least until we realize we can't.

Time and again on "It's Not Me, It's You," Allen -- who is in her mid-20s -- wonders aloud whether it's time to start acting like a responsible adult, even if she's not ready to do it quite yet. "22" is a music-hall ballad about a woman who's almost 30 and who's still waiting for "something" to happen: The line "She's got an alright job but it's not a career" practically says it all -- and naturally, everything would be closer to OK if only she had a man. "It's sad but it's true how society says her life is already over," Allen sings, buoyantly but with just a hint of resignation, as if she realizes how ridiculous that view is and still can't help being haunted by its curse.

And maybe it means something that the loveliest song on the record is the one that most readily embraces the comfortable if monotonous pleasures of adulthood. "Chinese" is, partly, a song about being on the road and being separated from the one you love. The protagonist waits for her bags at the airport carousel; she smokes a cigarette to help pass the time. But what she really wants is to get home, both just to her lover and to the routine of living: "Tomorrow we'll take the dog for a walk/ And in the afternoon then maybe we'll talk/ I'll be exhausted so I'll probably sleep/ And we'll get Chinese and watch TV."

As she sings those words, the wistful sweetness of Allen's voice is wrenching; without even consciously recognizing it, she has become more aware that pop music is all about being young -- until, that is, you're no longer young. After that, if a pop singer wants to preserve her career, she needs to find ways to preserve an element of youth within her maturity. What could be less fun? Or more challenging?

But for now, Allen is still safely just a girl, and thank goodness for that. Sometimes, in between making records, her antics have been a bit much: Famously, she's used her MySpace blog to gabble on about her own high jinks and to push back at her critics. Most recently, she's used her blog to plead with fans to buy her album, so she can reach No. 1 on the United States charts: "I've never begged you to buy from me ever, but I am now," she writes. "This will be the only time ever in my life that this could happen for me."

Her breathlessness is endearing, at least if you can get past the point that it's actually a sales ploy. But forget, for a minute at least, Allen's shrewd self-marketing. For now, she's still a one-person girl group, stretching out toward the adult world but still finding pleasure in the youthful search for love and happiness. "It's Not Me, It's You" is an exuberant record. Its status message, unspoken but understood, is "Doo-lang, doo-lang, doo-lang."

Shares