When François-Claudius Ravachol went to the guillotine in Paris on July 11, 1892, he gave one of the great performances in the history of "la Veuve" ("the widow"), as that ingenious beheading machine was often called. Ever since the French Revolution more than a century earlier, Dr. Guillotine's invention had provided kings, murderers and revolutionaries with the opportunity to make a dramatic exit, and huge throngs of Parisians turned out to watch them take their last steps and utter their final words.

Dignified to the end, Marie Antoinette reportedly apologized for stepping on the executioner's foot: "Monsieur, I ask your pardon. I did not do it on purpose." Her husband, Louis XVI, also faced the end bravely, although his attempt to give a long-winded speech forgiving his enemies and calling for God's mercy was, quite literally, cut short. Robespierre, the revolution's greatest orator, went to his death with his jaw shattered from a gunshot wound, and could say nothing.

Ravachol, an implacable enemy of the French state and any other form of government ever devised or imagined, outdid them all. Condemned to death for three murders -- one he admitted and two he probably didn't commit -- Ravachol was a true believer in anarchist revolution, an advocate of ruthless acts of violence that would point toward the inevitable destruction of bourgeois society.

Indeed, it was because Ravachol was perceived as a symbolic scourge of an era typified by excesses of blinding wealth and grinding poverty that his execution became an object of nationwide fascination. What he represented (or seemed to) was at least as terrifying to 19th-century France as Islamic fundamentalism is to 21st-century America. It may all seem a bit quaint and romantic to our eyes -- wild-haired European men in dingy frock coats, armed with dynamite and pamphlets by Proudhon and Bakunin -- but anarchism in the 1890s was understood as a major threat to the social order, a long way from the lentils 'n' dreadlocks postgraduate subculture it is today.

As Yale historian John Merriman tells the story in his fascinating new book "The Dynamite Club," Ravachol was all smiles on the morning of his execution. He told the priest who approached him with a crucifix, "I don't give a damn about your Christ. Don't show him to me; I'll spit in his face." On his way to the scaffold, he sang a song, possibly of his own composition: "To be happy, God damn it, you have to kill those who own property! To be happy, God damn it, you must cut the priests in two!" He tried to shout "Vive la révolution!" at the last moment, while his head was in the guillotine's cradle, but got only halfway through the phrase before the blade fell.

There are other episodes one could identify as central to the anarchism panic of the 1890s, which marked the Western world's first encounter with terrorism, at least as we use that word today. In fact, Merriman's book recounts the Ravachol case only as a preamble to its main story, which is about the bombing of a ritzy Parisian cafe two years later by a different anarchist, Émile Henry. But to me the transformative, even electrifying effect of Ravachol's execution makes it a history-shaping moment and marks the invention of something new and distinctively modern.

Ravachol was a good-looking, mustachioed rogue, but he was also a career criminal and a thoroughly incompetent revolutionary. He made several efforts to kill prominent magistrates and prosecutors with bombs made from stolen dynamite, but none caused more than minor injuries or property damage. (The one murder Ravachol definitely committed was not political; he robbed and suffocated an elderly monk in a remote hilltop village.) As a charismatic martyr for the cause of violent anarchism, however, Ravachol was a smashing success. His patently one-sided prosecution and courageous death made him seem a hero to many people who shared none of his political beliefs. He inspired numerous followers and sent a tangible wave of fear through the mainstream French establishment. (Asked at his trial whether he had any regrets, Ravachol said he only regretted the society he saw around him.)

Sympathetic journalists portrayed Ravachol as a "redeemer" and compared his "sacrifice and suffering" to those of Jesus Christ, also executed at age 33. A wood-block print by artist Charles Maurin, depicting Ravachol's defiant face framed by the guillotine, was widely reprinted and pinned to the walls of working-class houses all over France. The anarchist newspaper Père Peinard taunted the bourgeoisie: "Ravachol's head has rolled at their feet; they fear it will explode, just like a bomb!" Art critic Félix Fénéon, a prominent anarchist sympathizer, observed that Ravachol's execution had done more for propaganda than all the learned books and pamphlets of Peter Kropotkin, anarchism's leading theorist. For some time to come the executed murderer's name became a French verb; "ravacholiser" meant to assassinate someone with dynamite.

Terrorist acts are in part meant to provoke the state into a Draconian overreaction, and there too Ravachol succeeded. Panicked by wild assertions that a "dynamite club" of several thousand anarchists was planning to murder the upper classes en masse, the French government (and every other major European nation) enacted increasingly repressive laws that outlawed all anarchist books and publications, ordered all foreign anarchists expelled, and repressed "associations of evildoers," a fatally vague phrase that was applied to all sorts of opposition newspapers, political groups and intellectual gatherings.

Public opinion turned against the French intelligentsia, Merriman writes, for providing anarchism with some measure of respectability. One nationalist screed titled "On Intellectual Complicity and Crimes of Opinion" blamed the wave of 1890s bombings on pamphlets by anarchist forefathers like Kropotkin and Errico Malatesta, but also on Dostoevsky's "Crime and Punishment," which the screed's anonymous author called "an admirable manual for assassination." I know, it all sounds strangely familiar, even if Merriman, a judicious historian to the end, makes only the most passing reference to contemporary parallels.

Among those inspired by Ravachol was the aforementioned Émile Henry, whose bombing of the Café Terminus in 1894 is the principal subject of Merriman's book. Unlike Ravachol, who was raised by a single mother in extreme poverty and lived by odd jobs and petty crimes, Henry was a genuine son of the bourgeoisie who turned against his own tribe. He had grown up in a quiet country town just outside Paris, where his mother kept an inn. He excelled in school, and had barely missed admission to the École polytechnique, France's most prestigious college for engineers. (He could have reapplied, but never did.) He worked at various clerical and accounting jobs, where his employers invariably found him diligent and pleasant.

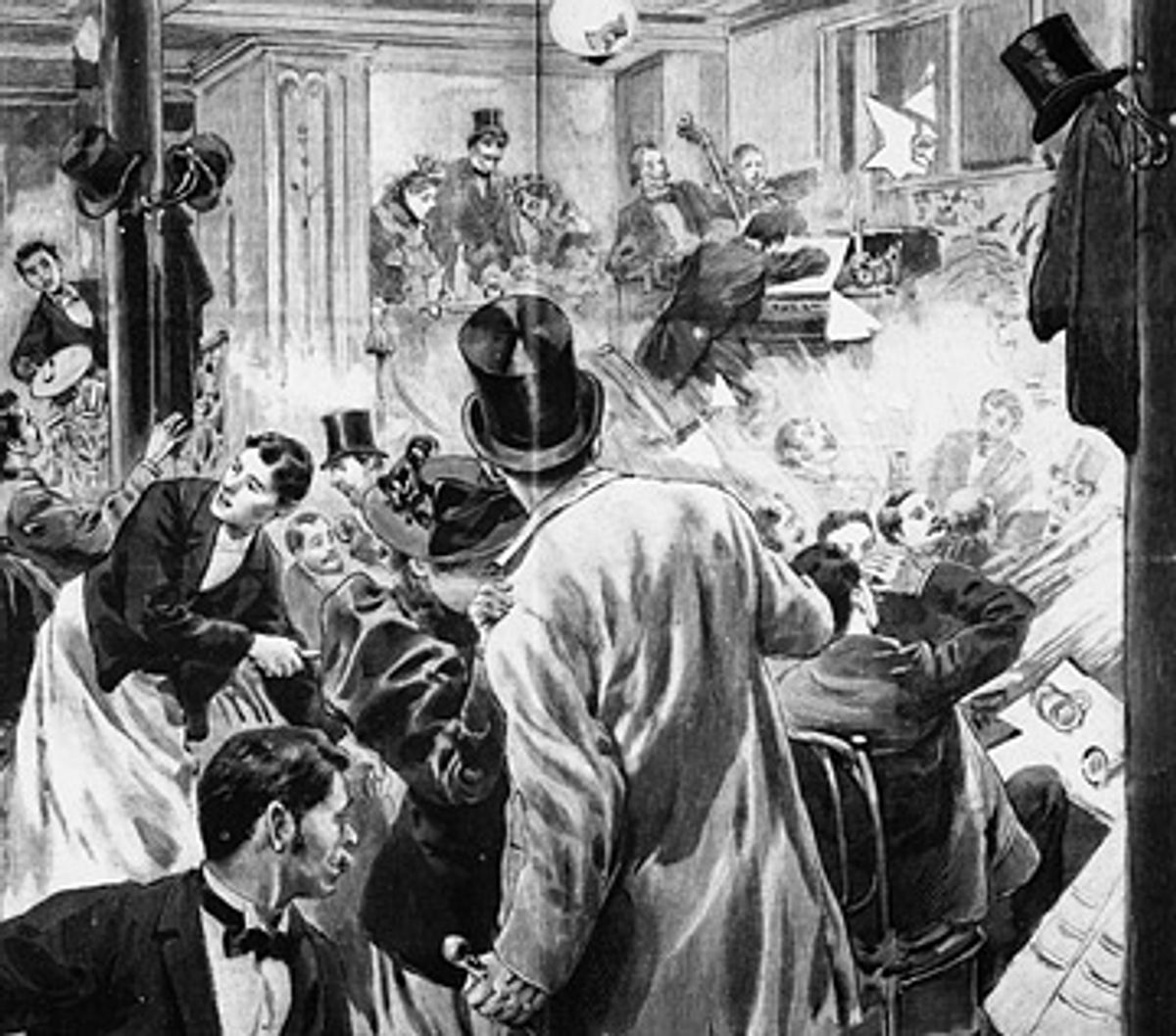

Yet somehow this promising and intelligent young man, who was initially horrified by Ravachol's indiscriminate bombings of apartment buildings, became the author of that era's most notorious attack. At about 8 p.m. on Feb. 12, 1894, Henry entered the Café Terminus, a big and bustling Gilded Age establishment around the corner from the Gare Saint-Lazare, where he ordered two beers and smoked a cigar. (He paid, even though he was about to blow the place up. A proper bourgeois after all.) An hour later, there were about 350 people in the place, and the orchestra was playing operatic music by Daniel Auber. Henry got up to leave. Once outside he took a homemade dynamite bomb, concealed in a workman's lunch-bucket, out of his overcoat, lit the fuse with his cigar, and threw the device behind him into the cafe, where it struck a chandelier, fell to the floor and exploded.

Only one person died in the Terminus bombing, which made it pretty wimpy even by Henry's standards. (His previous bombing, although aimed at a mining company, had killed three police officers, a secretary and an office boy.) There were dozens of injuries and a popular nightspot lay in ruins, but the real effect was psychological.

As Merriman sees it, this was the first time a political terrorist had envisioned ordinary people as a legitimate target, or attacked the public life of a major city. There are other candidates for this dubious honor: One could point to the spectacular "William Tell" bombing a year earlier in Barcelona, in which 22 theatergoers were killed. (Arguably that was more targeted, in the sense that the orchestra level of a luxurious theater was the province of the ruling class.) Whoever thought of it first, the point is that at least a few violent anarchists had moved rapidly from the theoretical notion that society should be destroyed to the idea that leaders of that society deserved to die and then to the sweeping conception that anyone who supported the existing society, even as a citizen and a consumer, was effectively guilty of crimes against humanity.

Henry spelled it out for his interrogators, shortly after his arrest: He hadn't been after a particular magistrate or attorney, in the manner of other anarchist bombers, "but rather the entire bourgeoisie, of which the former was only a representative." Café Terminus was a fancy enough place, but it also stood at the heart of an increasingly fluid metropolis and was in no sense exclusive to the rich. For the price of a coffee or a glass of beer, middle-class and even working-class people could and did drop in for a glimpse of the good life.

Henry understood as soon as he was arrested that he had no chance of avoiding the guillotine, and he admitted full responsibility for the bombing. The only defense he offered at his trial was a lengthy declaration of his ideas and motives. In his statement, Henry attacked the ordinary petit-bourgeois citizens of Paris, those who lived on 300 to 500 francs a month (a middle-class income, more or less) and who applauded the actions of the government and the police. They were "stupid and pretentious," he said, "always lining up on the side of the strongest."

Anarchists had no respect for human life, he said, because the bourgeoisie had shown none. "We will spare neither women nor children because the women and children we love have not been spared," Henry continued, making it clear that he was directly blaming the complacent classes for the misery that existed on the other side of the Gilded Age's shocking social divide. "Are they not innocent victims, these children, who in the faubourgs slowly die of anemia, because bread is rare at home; these women who in your workshops suffer exhaustion and are worn out in order to earn 40 cents a day, happy that misery has not yet forced them into prostitution; these old men whom you have turned into machines so that they can produce their entire lives and whom you throw out into the street when they have been completely depleted?"

He understood that he and many other anarchists would be killed, as Ravachol and others had been killed before him, Henry told the court. "But what you can never destroy is anarchy. Its roots are too deep, born in a poisonous society which is falling apart; anarchism is a violent reaction against the established order. It represents the egalitarian and libertarian aspirations which are opening a breach in contemporary authority. It is everywhere, which makes anarchy elusive. It will finish by killing you."

You can say many things about Ravachol's brutal, charismatic nihilism, and about Henry's colder and more rational argument that ordinary citizens should suffer the consequences for deeds they permit, even passively or unknowingly, to be done in their name. You can say that they're cruel and deranged, but taken together they possess an almost biblical clarity. For better or for worse, these two ideas are the twin pillars of terrorism -- the urge to destroy, and the moral rationale for destruction -- and they've been with us ever since. Allowing for differences in terminology and context, you could say that Ravachol and Henry's attitudes and arguments are essentially similar to those of Palestinian terrorists who send suicide bombers into Tel Aviv restaurants, or for that matter to those of Osama bin Laden.

Courtroom observers were mightily impressed with Henry's declaration. As one conservative journalist wrote at the time, "He is perhaps a monster, but he is not a coward." Yet when Henry himself went to his date with "la Veuve" early on the morning of May 21, 1894 -- he lacked Ravachol's swagger, but did shout "Vive l'anarchie!" on his way to the scaffold -- the crowd was relatively small, and public reaction afterward was muted. Henry never became anything close to a populist martyr; I guess telling the public it is stupid, pretentious and guilty of terrible crimes will do that.

Henry's execution marked the beginning of the end of the anarchist panic in France, even if it didn't feel that way at the time. (An extended anarchist panic in the United States still lay ahead, from the assassination of President McKinley by a laid-off factory worker in 1901 through the Wall Street bombing of 1920 and the Sacco and Vanzetti case in 1927.) A couple of aftershocks followed rapidly: French President Sadi Carnot was stabbed to death in his carriage on the main street of Lyon in June 1894, apparently in an effort to avenge Henry. Two months later the government arrested a group of 30 anarchists and supporters, including several leading intellectuals, and tried them on wide-ranging and flimsy conspiracy charges.

As Merriman reads the historical evidence today, both sides -- the French government and the anarchist left -- backed away from an escalating confrontation. Although he defended himself eloquently, Henry had done enormous damage to the anarchist cause. Relatively few anarchists had supported bombing campaigns to begin with, and even those who believed in revolutionary violence saw a big difference between blowing up judges and blowing up cappuccino drinkers. Pioneer Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta had warned: "Hate does not produce love, and by hate one cannot remake the world."

At the same time, after the "Trial of the 30" collapsed in the autumn of 1894, with all the intellectual defendants acquitted, the French government gradually abandoned its most repressive measures. In Merriman's view, the attempt to crush anarchism had resulted only in a worsening climate of class hatred and in more bombings and killings. When anarchists were allowed to come up from underground, they channeled their "egalitarian and libertarian aspirations" into nonviolent political activities. Many became involved in the labor movement that would reshape 20th-century France as a social-welfare state, significantly lessening the brutal economic divisions that had fueled revolutionary violence in the first place.

Are there lessons in this history that apply to the "war on terror" recently inherited by the Obama administration. Merriman's general principle seems to be that in this kind of crisis, both the terrorists seeking to overthrow established order and the authorities seeking to crush them tend to overreach themselves. Each side is likely to do more damage to its own cause than to its purported enemy. I mean, think about it: Which will be worse for the United States over the long haul: 9/11 or Guantánamo Bay?

There are murkier, more psychological realms beyond that where a mainstream historian like Merriman simply isn't going to venture. These lie in the terrain first explored by Marx and Freud, those semi-discredited totems of the last century, and in a question that Ann Coulter and Noam Chomsky might answer in the same way: Does Western civilization contain the seeds of its own destruction? Or to put it another way, will Ravachol and Henry always be with us?

For Marx, this was a question of historical inevitability: The advanced industrial economy of capitalism would produce one commodity above all others, a worldwide proletariat that would smash capitalism. For Freud, this was a question of an endless, irresolvable struggle within the self and within society, a struggle between Eros and Thanatos, between sexual desire and the death wish. For a massively influential strand of 20th-century philosophy rooted in the "Frankfurt school" of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, this was the "dialectic of Enlightenment" -- the idea that the cultural and scientific flowering of modernity had also produced the death camps and the atom bomb.

French philosopher Jean Baudrillard's widely misinterpreted remark that America had secretly desired a calamity like 9/11 belongs to this tradition. It was not an apology for terrorism but an attempt to make sense of it within an analytical framework (albeit a controversial one). With increasingly rare exceptions -- John Walker Lindh in one direction, Timothy McVeigh in another -- Western society in its late consumer-capitalist phase no longer produces its own internal enemies. The job of being the nihilist force that aims "at nothing less than the destruction of all that exists," in the phrase of an outraged French legislator, has been outsourced.

As either Bill or Ted observes in one of their excellent adventures, those who forget the pasta are doomed to reheat it. In a time of economic crisis bordering on catastrophe, it's tempting to speculate once again that Western civilization teeters over the abyss, its enemies closing in on all sides. One of these days the gloomsayers may be right. But on the evidence available to date, capitalism has a way of absorbing these things after it produces them. By the afternoon of Feb. 13, 1894, a day after Émile Henry's bomb, the Café Terminus was open for business. The windows were smashed and there were visible bloodstains on the floor, and anybody who was anybody in Paris wanted to take a look. And maybe enjoy a beverage or two.

Shares