It could have been a guy in that science-fiction bookstore that used to be under a parking garage in downtown Berkeley, Calif. Or it could have been that Korean guitar player and drug dealer who told me he had taught himself English as a small child by studying the people dressed as toasters on "Let's Make a Deal." It's hard to remember after all this time. But at some point in the spring or summer of 1984, someone put a copy of "Saga of the Swamp Thing" in my hand and said, "Hey, man. Have you seen this?"

It seemed like a stupid question. Of course I remembered "Swamp Thing." It was a DC Comics franchise launched in my childhood, an entertaining fusion of the superhero comic and the horror comic that half-accidentally coincided with the birth of the modern environmental movement. Its hero was a human-vegetable hybrid named Alec Holland, an assassinated government scientist who had been mysteriously reincarnated in a Louisiana swamp. Like a lot of other kids my age, I had read "Swamp Thing" for a while in the '70s before moving on to various pretend-grown-up obsessions: Roxy Music and the Rolling Stones, Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Buñuel and Nicolas Roeg.

Along the way the "Swamp Thing" comic had died and been reincarnated, largely because of Wes Craven's raunchy, comical and decidedly mediocre 1982 film version. Petit-snob that I now was, I assumed that the reborn DC "Swamp Thing" was nothing more than lame, bottom-of-the-barrel, based-on-the-movie cultural debris. And then someone gave it to me with a sense of peculiar urgency and I read it.

I have no idea what the first 19 issues of the revived "Swamp Thing" (written by Martin Pasko and drawn by Tom Yeates) were like, and comics fandom being what it is, I'm sure they have admirers. But when Pasko left abruptly with several plot strands hanging in midair, DC editor (and "Swamp Thing" creator) Len Wein asked a young English comics writer to come over from London and give Alec Holland's universe a whirl. That guy's name was Alan Moore, and his best-known work at that point was the apocalyptic political thriller "V for Vendetta," a work inspired by Orwell and Pynchon that seemed a world away from American superhero comics. But Moore told Wein he'd do it, as long as he got a free hand to reshape "Swamp Thing" and its protagonist as he wished.

So it began. Long before anyone had started using the pompous term "graphic novel," long before Moore became the reclusive genius behind "From Hell" and "The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen" and, of course, the about-to-be-a-massive-motion-picture "Watchmen," came his remarkable mid-'80s run on "Saga of the Swamp Thing," which redefined both the audience and the narrative possibilities of comic books.

It would be insulting to the genre and its readers, as well as fundamentally untrue, to say that Moore reinvented comics. Moore loved comics, in all their overheated melodrama and violence and passion and romance, and simply wanted them to fulfill their potential. He wanted comics to be better written (and more beautifully drawn; he has consistently brought out the best in his artists), to be more alive to the outside world and to other forms of culture, to be less imprisoned by the emotional ghetto of pre-adolescence.

DC's new archival hardcover edition of "Saga of the Swamp Thing: Book One" is by no means the first collection of Moore's "Swamp Thing" efforts, but the higher-quality binding and printing make it the one hardcore aficionados will want. Instructively, it also includes Moore's first issue (No. 20, from January 1984), which has never before been anthologized, perhaps because it's mostly devoted to wrapping up Pasko's unresolved story lines. That issue features the discovery of a disfigured, not-quite-human corpse, a sinister government conspiracy, a hotel-room bombing and an over-the-top firefight involving flamethrowers and helicopter gunships, then as now the stuff of comic books.

Nine pages in, Issue 20 also features an internal soliloquy by Alec Holland, aka the Swamp Thing, addressing his recently dead archenemy in a lyrical, regretful mode that may have puzzled some 1984 readers but rapidly became identified as a hallmark of Moore's style: "It's a... new world, Arcane. It's full of... shopping malls and striplights and software. The dark corners are being pushed back... a little more every day. We're things of the shadow, you and I... and there isn't as much shadow... as there used to be. Perhaps there was once a world... we could have belonged to... Maybe somewhere in Europe... back in the fifteenth century, the world was... full of shadows then... full of monsters... Not any more." (Those idiosyncratic ellipses are in the original.)

Later in the issue, not long before Swamp Thing is gunned down by what seems to be an entire company of United States Army infantry with air support, there's the sinister female motel clerk who delivers a stream-of-consciousness retelling of the climactic scene in Roeg's pseudo-surrealist horror film "Don't Look Now," concluding with the laconic phrase "... and Donald Sutherland gets it right in the neck." Then the bomb in her hotel goes off, a horizontal-diagonal spray of red and black and orange and yellow with the word "THROOM!" shooting across it toward the reader.

Moore was just getting started with "Swamp Thing." There were no quotations from Goya or James Agee in Issue 20, no demons speaking in faux-Elizabethan rhyming couplets, no appearances by Satan or by Dr. Jason Woodrue, aka the Floronic Man, a minor DC villain whom Moore reconceived as a deep-ecology activist turned genocidal lunatic. (Hearing a woman cry, Woodrue tells himself, "If there's one thing that I despise, it's the sound of steak sobbing.") But two things are clear: Moore knows what comics readers want and intends to give it to them, and whether or not they want something more complicated, more tragic and more adult (I know it's a loaded word), he's going to give them that, too.

DC's initial hard-bound volume comprises Moore's first eight issues as the writer of "Saga of the Swamp Thing," covering Swampy's battles with Woodrue and an especially terrifying demon called the Monkey King, who visits children in their dreams and preys upon their worst fears. (In case you're wondering, "Nightmare on Elm Street" was released several months later. Any resemblance is presumably coincidental.) Moore's stories crackle with tension and he's a master of what might be called comic-book enjambment, in which the last line of a given scene becomes the first line of a new one, on a different plotline with different characters.

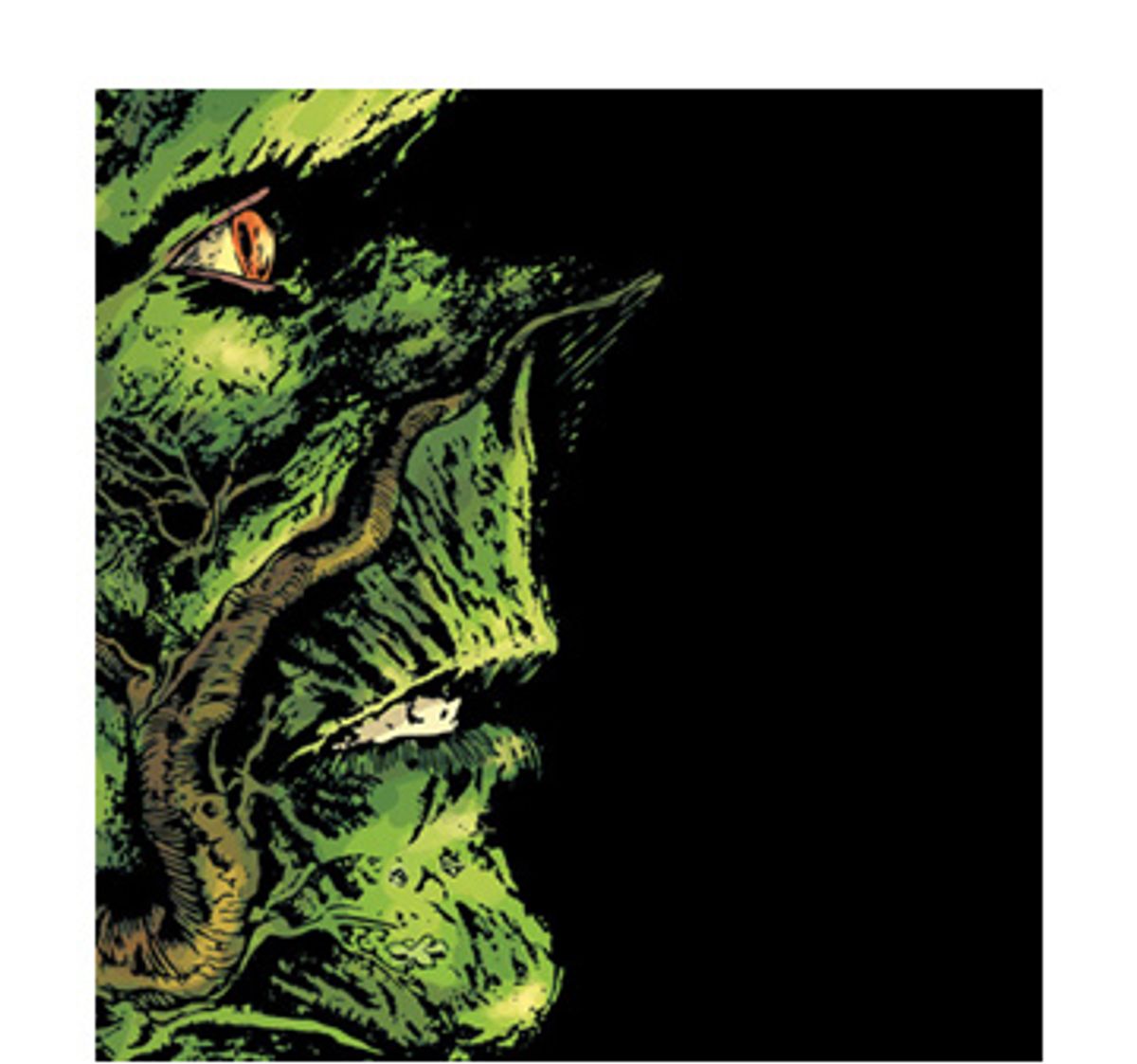

More striking than Moore's technical excellence, of course, was his conceptual brilliance, along with the simpatico quality of his partnership with artists Stephen Bissette and John Totleben, who seemed eager to push their form into the frequently phantasmagorical dimensions that Moore's prose demanded. These issues mark the startling transformation of Swamp Thing himself, a cuddly-cum-monstrous figure whom Moore clearly found unsatisfactory and poorly conceived.

Alec Holland, Moore decided, was long dead. Swamp Thing was not a plant-creature who used to be human, but a form of vegetable intelligence that had literally digested Holland's consciousness, and became briefly convinced that it was human. As later issues would reveal, Swamp Thing was connected to "the Green," a global, mystical, collective awareness that connected the South American rain forest to the African grasslands to the redwoods of California to the Louisiana bayou where he periodically took root (and grew edible, yamlike tubers, one of them consumed by Jason Woodrue with unfortunate results).

I think it's no exaggeration to say that Moore models Swamp Thing's ensuing existential predicament on that of Hamlet. In an extended, hallucinatory dream sequence that features giant talking planarian worms and a spoof of the "Alas, poor Yorick!" monologue, Swampy must decide whether to continue his ambiguous existence armed with the knowledge that he was never human and never will be. In essence, he decides that "to be or not to be" is not a binary equation, and chooses both options.

It's been said that Moore was ahead of his time by infusing a holistic, ecological perspective into comics in 1984, and that his anti-authoritarian politics, sometimes bordering on anarchism, were unusual and daring amid the so-called Reagan revolution. But that overlooks the fact that the radical environmental movement was rapidly gaining steam among the American left -- Earth First! had been founded in 1979 -- and in a climate of deepening economic recession and widespread youth unemployment (hello!), the summer of 1984 would see large, anarchist-influenced "punk protests" at the Democratic convention in San Francisco.

Moore was right on time and right on message for a specific micro-generation of young people who were disillusioned and disgusted by Reaganism, and had lost any sense of connection to the American dream. Our consciousness had been shaped -- as Moore's clearly was -- by Joe Strummer and Johnny Rotten (Moore had actually written a screenplay for Sex Pistols impresario Malcolm McLaren), by Kurt Vonnegut and Thomas Pynchon, by campus organizing against apartheid and the U.S. proxy war in El Salvador. With his near-total divorce from human ethics balanced by his planetary consciousness, Swamp Thing became perhaps the first postmodern comic-book hero.

I won't try to claim that "Swamp Thing" is always Moore's best work. Over the course of his four years at the helm, the quality of the artwork waxed and waned, and occasional plotlines ran on comic-book autopilot. More than any other comics writer of his time, Moore strove to reach female readers, but in that format I doubt he found many. Still, there's a fresh and often startling quality to "Swamp Thing," at least for me. I've read this series at least twice before, but I'm excited for the next volumes to arrive, some of them darker and stranger than this one. If memory serves, Swamp Thing will visit heaven and hell, hear firsthand reports from the dead about God, tangle with a feminist werewolf, channel characters from H.P. Lovecraft stories and Walt Kelly's "Pogo," and, perhaps most memorably, consummate his romance with the lovely but haunted Abby Cable in an act of human-vegetable communion unlike anything else in the Western artistic and literary tradition.

Of course, with the possibilities Moore began to map out in 1984 so extensively fulfilled, and the graphic novel entrenched as a respectable literary form, "Saga of the Swamp Thing" may strike contemporary readers as nothing more or less than a cool horror comic, high in philosophy and in grotesque imagination. Maybe you had to be there to appreciate that Moore did more than remake a half-baked '70s comic-book hero as a mystical eco-avenger, and explore new possibilities for the 24-page illustrated monthly serial. He gave a generation of suburban nihilists, fueled by black coffee and loud guitars and soulless temp jobs, a creature from the swamp who seemed to embody their desire to destroy and their urge to create. It was something to believe in, at last.

Shares