It's a mistake to view "Tokyo!" -- an omnibus project comprising three short features, two of them made by Frenchmen (Michel Gondry and Leos Carax) and one by a Korean (Bong Joon-Ho) -- as a love letter to Japan's sprawling yet cramped metropolis. There's nothing so certain as love woven into the bumpy and sometimes perplexing texture of "Tokyo!" This isn't an art house crowd pleaser along the lines of the 2006 "Paris, je t'aime," a freewheeling mixed bag of shorts made by the likes of Olivier Assayas, Wes Craven and Alfonso Cuarón. "Tokyo!" demands more patience, patience that it sometimes doesn't deserve.

But whenever I hear that a picture "received a lukewarm reception at Cannes" -- just one of the charges that's been leveled at "Tokyo!" since it played there last year -- I usually make a note to check it out, simply because festival groupthink drives me nuts (since it never makes allowances for even a bad film's interesting idiosyncrasies).

And the reality is that "Tokyo!" is a defiantly odd picture -- its middle portion, in particular, directed by the always strange Carax, isn't out to win any friends. But the refusal of "Tokyo!" to proffer even the most perfunctory air kiss is what makes it so intriguing. There's nothing here that makes the city seem beautiful, warm or welcoming. Talk about damning a city, and its people, with faint praise.

The sections of the film made by Gondry and Bong both feature characters who feel intense isolation, or who are searching for a sense of belonging or purpose. In Gondry's "Interior Design," a young couple, Hiroko and Akira (played by Ayako Fujitani and Ryo Kase) trek to Tokyo to start new lives for themselves. Akira wants to be a filmmaker, and we get to see a portion of his handiwork, which features some crudely executed surreal special effects, like a woman giving birth to a white rabbit. (It emerges from a birth canal that appears to have been constructed of cardboard slathered with red goo.) If you ask me, this ostensibly bad film-within-a-film looks a lot more interesting than the idiotic whimsy Gondry usually churns out for real (Exhibit A: "The Science of Sleep)," but never mind that. The focus here is on Hiroko, a sweet-tempered girl who isn't as certain of her ambitions as Akira is. Then she undergoes a life-changing event that gives her a sense of purpose (and also gives Gondry the chance to use some simple but arresting special effects).

There's no grand meaning behind "Interior Design," which reduces Tokyo to a series of storefronts and narrow streets. (In fact, none of the movies here gives us the usual view of the city as an ultramodern Emerald City made of blinking towers of neon -- analogous to the way New York isn't "just" Times Square, although the movies sometimes make it seem that way.) But "Interior Design" does capture the essence of what it means to find one's place in a new and overwhelming environment.

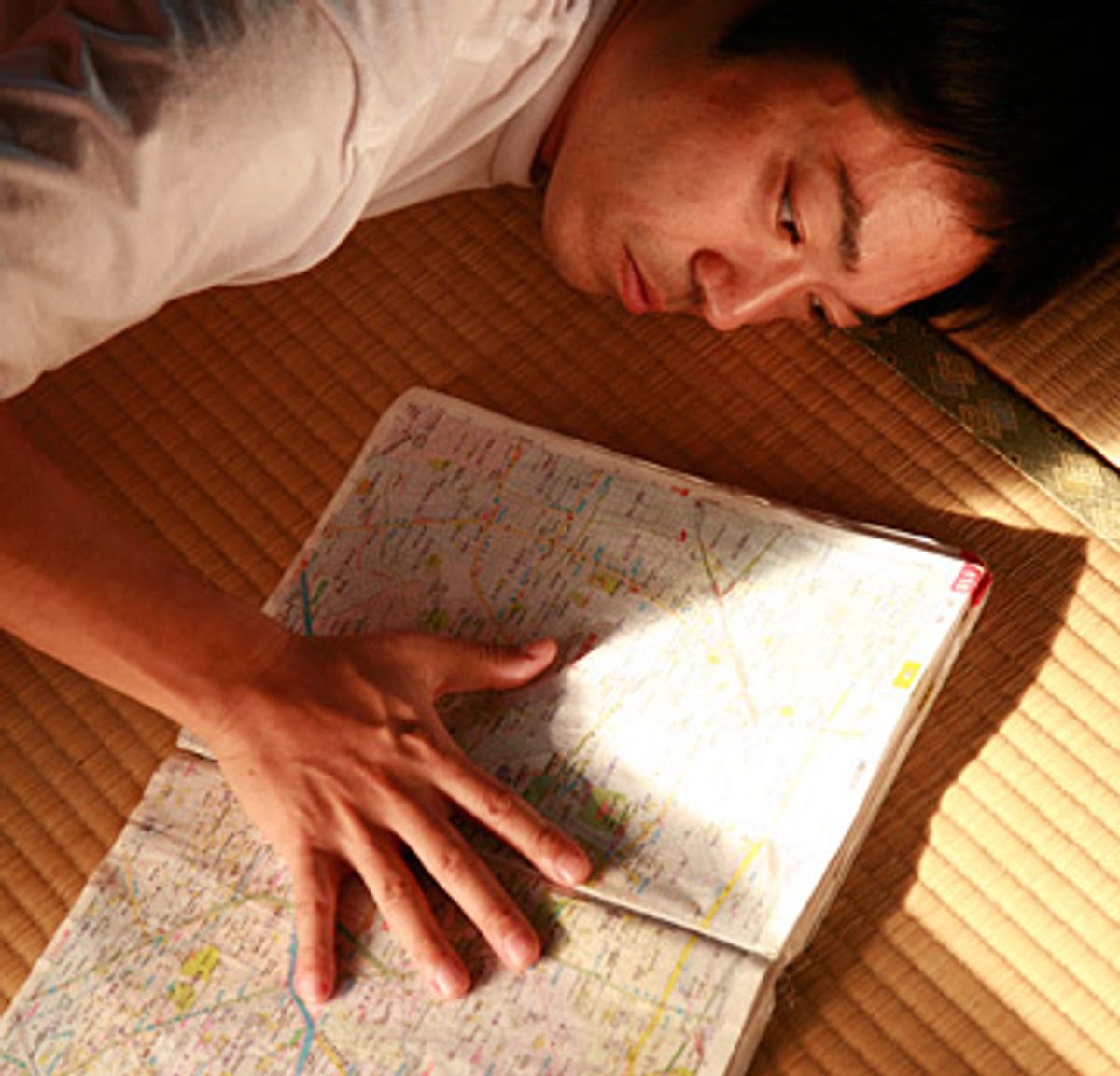

Bong's "Shaking Tokyo," meanwhile, explores what it means to retreat from that environment -- to hide yourself away from both the trauma and the joy that come with city life. Teruyuki Kagawa plays a shut-in -- the Japanese would call him a hikikomori -- who hasn't left his apartment in 10 years. He's also a hoarder: Instead of putting his empty pizza boxes and cardboard toilet-paper tubes in the garbage, he stacks them into neat arrangements that resemble museum installations. What happens when boy hikikomori meets girl hikikomori? Our shut-in finds out after he meets a strange, shy pizza-delivery woman.

With "Shaking Tokyo," Bong (the director of the 2006 quasi-political creature feature "The Host") gives us a quiet, light-as-air little love story, punctuated by earthquakes -- they're less an act of God than a symbol of the way our feelings exist in a universe that's out of our control. Like Gondry's feature, "Shaking Tokyo" is small, personal and intimate -- pleasant enough, if also inconsequential.

So what to make of the Leos Carax firebomb, "Merde," that explodes the center of "Tokyo!"? (You may recognize that title as the French word for shit.) I've had a week to think about "Merde," and I still don't know what to make of it. The star here is Denis Lavant, the odd and wonderful French actor who has appeared in several of Carax's films, including "Mauvais Sang" (1986) and "Lovers on the Bridge" (1991), as well as Claire Denis' 2000 "Beau Travail" -- although Levant may be best known to American audiences for his starring role in a longish Stella Artois ad, shown in art house movie theaters a few years back, in which his character takes great pains to bring his dying father a glass of the lager.

Playing an angry gnome who lives in the sewers of Tokyo, Levant has a scowling, preternaturally annoyed-looking face -- his features seem pushed in, like the visage of a comic-book character rearranged via Silly Putty. One day he emerges from the underground into the sunlight, dressed in a too-small green suit: His hair is a dirty, matted reddish mass. His nails have gone uncut for so long they've become curvy animal talons. His beard is like a cedilla sprouting from his chin. And his eyes are two pools of crazy -- or they would be, if one of them weren't an impenetrable milky white.

Our little sewer-dwelling friend strides through the streets, past rows of luxury shopping establishments, terrorizing the innocent citizens. From their hands he grabs money and flowers, both of which he proceeds to eat -- petals and shreds of currency fall from his mouth like fluttery crumbs. He grabs a cigarette from a shocked bystander, takes a few puffs, and then stubs the thing out in a baby's carriage.

The opening of "Merde" is like a Buster Keaton short gone mad, and within it, Levant's performance is a grand physical turn that would do Keaton proud. And from this very strange opening, "Merde" gets stranger, more violent and much darker. After this sewer creature is captured and brought to trial (he communicates in a grunting language that only a few other men on earth can understand), we learn that he hates the Japanese. His reasons? "They live too long, and their eyes are shaped like a woman's sex." There are also overt allusions to the horrors of Nanking; at one point he asserts that the Japanese raped his mother.

What the hell is "Merde" about? I'm sorry to tell you that I have no earthly idea and can venture only a few tentative theories. Carax is the shadow man of French film: His movies tend to be strange and impenetrable (some would say they're willfully so, although I think there's something bracingly vital about their weirdness), and he hasn't made a feature since the 1999 "Pola X." What, exactly, is Carax trying to say with "Merde"? Is he trying to hold a country accountable for its past sins? Is he pondering the idea that it's one thing for a crazy person to hold a racist grudge forever, but sane and rational people must be the ones to forgive?

I think there are seeds of both of those ideas in "Merde"; Carax refuses to lay anything out clearly, and his obtuseness is maddening. But I found the outlandish spectacle of "Merde" exhilarating as well as confounding. Or maybe it's exhilarating because it's confounding. I wish "Merde" had been programmed as the last featurette in "Tokyo!," although it was probably deemed, rightly, to be too much of a weirdo downer. You don't want to send the audience walking home on a cloud of perceived or actual racism. But I will say this: If "Merde," even as part of a triptych, gets that blanket festival "lukewarm reception," you know the tastemakers are all smoking from the same pipe. Perhaps "Merde" is just too aggressively bizarre, for no good reason. But sometimes a movie that makes you ask, "What the hell was that?" can be its own reason for existing. Especially when the filmmaker himself is bold enough to call it shit.

Shares