When Donald Rumsfeld heard about plans to force detainees at Guantánamo Bay to stand for hours on end, in order to soften them up and make them talk to U.S. interrogators, he made a joke about it. "I stand for 8-10 hours a day," the then-defense secretary wrote on Dec. 2, 2002, at the bottom of a memo authorizing military officials to use extreme techniques against prisoners. "Why is standing limited to 4 hours?"

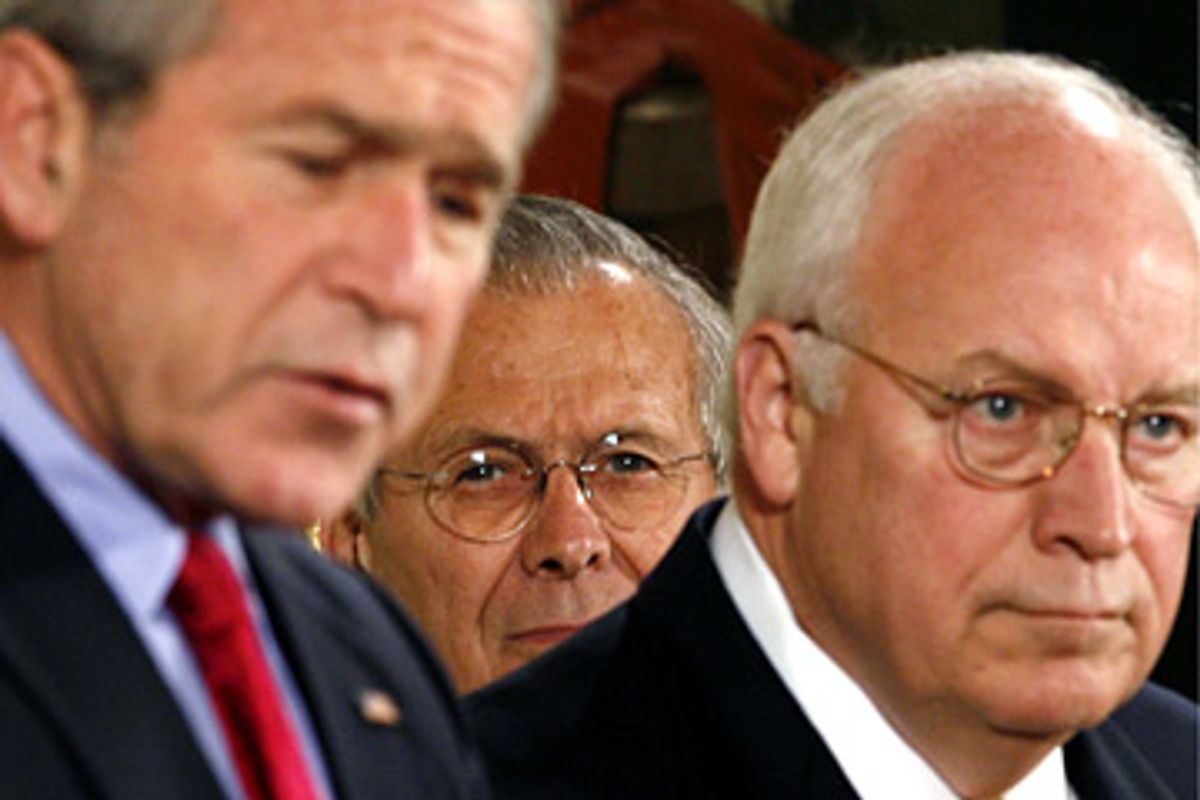

As a newly released Senate Armed Services Committee report makes clear, the effects of Rumsfeld's cavalier attitude toward what the report calls "detainee abuse" -- and what international law would probably call torture -- didn't just stop at the military prison on Cuba. The techniques Rumsfeld approved for use at Guantánamo oozed into prisons in Afghanistan and Iraq, undermining decades of U.S. policy about humane treatment of detainees and leading to some of the worst outrages of the Bush administration, including the Abu Ghraib abuses, which Salon has covered extensively.

"The abuse of detainees at Abu Ghraib in late 2003 was not simply a result of a few soldiers acting on their own," the Senate report says. "Interrogation techniques such as stripping detainees of their clothes, placing them in stress positions and using military working dogs to intimidate them appeared in Iraq only after they had been approved for use in Afghanistan and at [Guantánamo] ... Rumsfeld's authorization of aggressive interrogation techniques and subsequent interrogation policies and plans approved by senior military and civilian officers conveyed the message that physical pressures and degradation were appropriate treatment for detainees in U.S. military custody. What followed was an erosion in standards dictating that detainees be treated humanely."

The Bush administration, including Rumsfeld, all treated Abu Ghraib as the actions of a few rogue soldiers. Eleven enlisted personnel were convicted of crimes because of the way they treated Iraqis held there; the longest sentence, 10 years, went to former Cpl. Charles Graner. (One officer, Lt. Col. Steven Jordan, was convicted of disobeying an order not to discuss the case, but acquitted on more serious charges.) But the Senate investigation, completed last fall but only released this week, found the abuses there -- forcing prisoners into "stress positions," stripping them naked, menacing them with dogs -- were directly inspired by similar behavior top administration officials had already approved elsewhere.

"Rumsfeld's authorization of aggressive interrogation techniques for use at Guantánamo Bay was a direct cause of detainee abuse there," the report says. The approval from the defense secretary "influenced and contributed to the use of abusive techniques, including military working dogs, forced nudity and stress positions, in Afghanistan and Iraq." Salon reported on Rumsfeld's early involvement in the development of the interrogation programs in 2006.

A matter-of-fact narrative with a clinical tone, the Senate report runs through exactly when various military and civilian officials knew about and authorized what kinds of behavior. And it adds a bitter irony to Rumsfeld's claims that he only learned about Abu Ghraib after the worst abuses had already happened (he later called the day he heard about the prison scandal "the worst day" of his tenure at the Pentagon).

Top Rumsfeld aides were already laying the groundwork for torture barely two months after the 9/11 attacks, and just weeks into the war in Afghanistan. The Pentagon's general counsel's office contacted the military agency that runs the Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape programs -- schools where U.S. personnel and contractors are taught how to resist abuses that prisoners of war have been through before -- in December 2001 to find out how the SERE training could help interrogators break al-Qaida suspects. Military officials at the time told top Pentagon aides that the SERE techniques produced "less reliable" information.

By the spring of 2002, Cabinet-level Bush aides -- including Rumsfeld, then-National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, then-CIA Director George Tenet and then-Attorney General John Ashcroft -- began evaluating the CIA's plans to set up an interrogation program at Guantánamo using tactics developed by the SERE schools. The Justice Department's memos giving legal cover for the techniques were written that summer. In October 2002, military commanders at Guantánamo asked the Pentagon to okay the techniques. Uniformed military lawyers had decided they needed approval from Rumsfeld, because otherwise what was being proposed would be illegal. "It would be advisable to have permission or immunity in advance" before carrying out the interrogations, wrote a staff lawyer at the Guantánamo base, Lt. Col. Diane Beaver. Her analysis found the tactics would constitute a "per se violation" of military law, the report says.

The day before Thanksgiving in 2002, Rumsfeld's general counsel, William Haynes, recommended that his boss authorize "use of mild, non-injurious physical contact such as grabbing, poking in the chest with the finger and light pushing," as well as stress positions, stripping naked and dogs. Rumsfeld approved the request on Dec. 2, attaching his hand-written joke about standing to the memo. (As defense secretary, Rumsfeld used a standing desk with no chair.)

Military lawyers almost immediately began to object to the newly approved techniques. The Navy's general counsel, Alberto Mora, spoke with Haynes three times between December 2002 and January 2003, saying what Rumsfeld had authorized "could rise to the level of torture." Because of the pushback, Rumsfeld revoked authority for the interrogation techniques on Jan. 15, 2003, and set up a new "working group" at the Pentagon to come up with ways to handle suspected terrorists without breaking the law.

But by the spring of 2003, the Pentagon decided to plow ahead with torture. Though lawyers on the working group said they were worried about the SERE-inspired tactics, Pentagon officials wound up relying on a March 2003 memo by John Yoo, a Justice Department lawyer, which said laws banning torture didn't apply to interrogation of "enemy combatants." Possibly hoping to head off a conflicting report, Haynes had asked Yoo to write up the memo when the working group convened. Yoo's memo was, in turn, based on one written in August 2002 by Jay Bybee.

On April 16, 2003, Rumsfeld authorized 24 techniques at Guantánamo including sleep deprivation, messing with detainees' diets and pretending the interrogators were from a different country -- one where torture was even more acceptable -- in order to scare them into cooperating. And he told commanders to ask him for permission to use additional techniques.

From there, it was only a matter of time before the tactics spread. "The techniques -- and the fact that the Secretary had authorized them -- became known to interlocutors in Afghanistan," the Senate report says. Rumsfeld's memos authorizing dogs in Guantánamo quickly arrived at Bagram Air Force Base in Afghanistan. SERE school trainers, who had developed the interrogation techniques at Gitmo, started showing up in Afghanistan and Iraq. The techniques became standard operating procedure.

By 2004, when news of the abuses at Abu Ghraib got out, the military had already grown accustomed to a culture of abusive interrogation that made that scandal possible -- even if the Bush administration tried to claim it was a blip in an otherwise clean record. And as the Senate report makes clear yet again, that culture came about thanks to Rumsfeld.

Shares