By going bankrupt, Shabby Chic staved off an ugly showdown that has loomed over my household ever since my wife fell in love with one of its couches. By vanishing into a Chapter 11 void, it pulled the plug on one of those money-based marital disputes that constitute the most powerful argument for a solitary existence -- in this case, whether to drop $5,000 on a sofa.

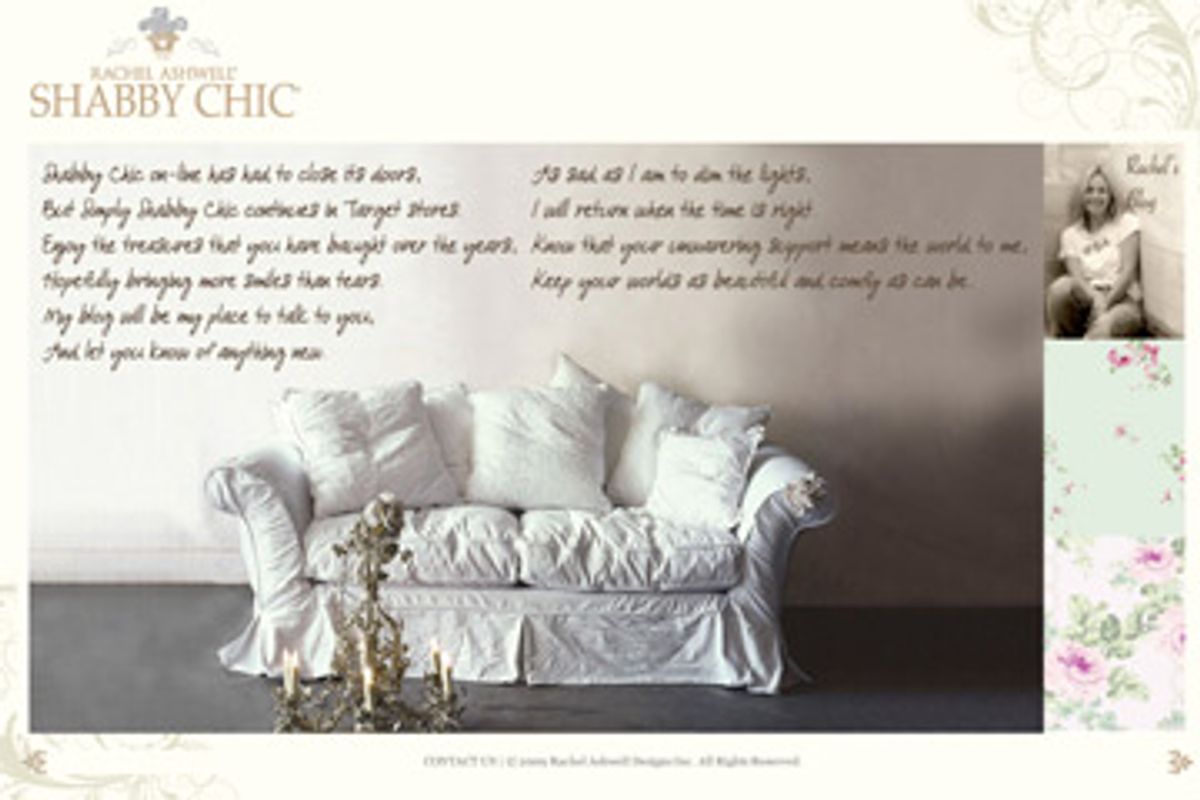

But before we get into that, let us pause to remember the dearly departed. Shabby Chic is, or was, a small California-based retail chain, started in 1989 by a British-born Los Angeles resident named Rachel Ashwell, which specialized in furniture, bedding and other domestic knickknacks, all done in the eponymous "shabby chic" style. That style, which predates Ashwell's company but which she helped popularize, aims at re-creating the comfortable, well-worn ambience of an old English country house. It typically features old furniture that has been repainted with several coats and then sanded to give it a distressed look, vintage linens, pillows and cushions, floral motifs -- especially roses -- a palette dominated by white, pastel and faded-Mediterranean colors, and a generally classy-feminine feel. It has a distinct found-treasure, flea-market aesthetic.

Shabby Chic -- the company, not the interior design style -- was never huge, but it was a solid and successful business, with eight stores, all but two in California, generating about $10 million a year in sales. Ashwell, a former movie-set designer and stylist and mother of two, wrote several books, was featured on "Oprah" and even had her own TV show for a while. She also signed a licensing agreement with Target, which carried (and still carries) a lower-priced spinoff line, Simply Shabby Chic.

Since Ashwell's aesthetic happens to be pretty much identical to my wife's, we would pop into the elegant Shabby Chic store on San Francisco's tony Fillmore Street from time to time. Inevitably we would find ourselves in the midst of people -- mostly women -- who were at least several rungs above us on the bourgeois ladder. As we sank into one of the obscenely comfortable $10,000 sectional couches on the floor, we knew we couldn't buy it: We were simply subjecting ourselves to Monty Python's most fiendish torture, the Comfy Chair. But those tastefully dressed, tanned, Yoga-class-attending, simplicity-movement-embracing, Lexus-driving, youthful-middle-aged San Francisco ladies were actually buying things.

Shabby Chic was grossly overpriced. But the merchandise was of pretty high quality, and the price wouldn't daunt someone in the tax bracket that Joe the Plumber aspired to join. Besides, there were always a few tchotchkes around that anyone could afford. The ladies we saw in the S.F. store were presumably Shabby Chic's core clientele, and their ilk are still very much around in cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles and New York. And even though they may not have quite as much disposable cash to drop as they did before America moved into its pre-Weimar phase, they might have been able to keep Shabby Chic alive.

In her blog, Ashwell says that the main thing that doomed the company was her decision to dramatically expand it at exactly the wrong moment. In 2007, Ashwell signed a deal with a private equity firm, hired new management and quickly opened about 10 new stores, with plans to eventually open 65 stores across the country. A piece in Entrepreneur magazine, which bore the unintentionally ironic title "When Success Isn't Enough," lauded her move to the "next level."

Alas, the "next level" turned out to mean that Big Off-White Duvet Cover in the sky. With the economy cratering, some of the new stores lost more money than they made, and with home-furnishing sales down across the country, the original stores didn't bring in enough to stop the bleeding. When Shabby Chic filed for bankruptcy protection this year, it owed its creditors about $28 million.

Few if any zeitgeist-y conclusions can be drawn from the death of Shabby Chic. It's easy to poke fun at it as a company whose raison d'être was to make the flea-market aesthetic safe for the well-heeled (and make them pay for the privilege). And there is something contradictory about pre-packaging a design style that is based on being able to see the creative possibilities in a piece of old junk. But Shabby Chic wasn't a worse offender in that regard than Martha Stewart. Nor, with a few exceptions, was its merchandise excessively affected, "quaint" or cute. It was a tad girly for my taste at times, but basically, it made beautiful and cool old things, or things in an old style, accessible for anyone who had enough money to pay its excessive markup. That's hardly a mortal sin.

Shabby Chic's formula certainly isn't going away. With hard times upon us, more consumers will cut out the middleman, and even some upper-middle-class people may decide to start haunting flea markets and used furniture stores themselves. But that's time-consuming and unpredictable. The national chain Anthropologie, which works some of Shabby Chic's design terrain at lower prices, still seems to be going strong.

Before we bid farewell to Shabby Chic, let us return to where we came in -- the $5,000 couch. The thing was $2,000 too high, which is where the potential for "Everybody Loves Raymond"-esque marital unpleasantness came in. But it was also the most comfortable couch I have ever sat on. And as I become increasingly prone to thinking with my derriere, it is not inconceivable that I might have gone for it. Shabby Chic's demise, sad for its owner and its employees, is thus a win for me any way you look at it: It averts flying crockery, potentially saves me $2,000 and allows me to deny my inner Stegosaurus. And if the company would just come back with everything permanently marked down 70 percent, I'd be wallowing in so much distressed, faux-Provençal, creamy white, rose-stenciled stuff that you'd have to sandpaper 10 layers of tastefully chosen paint off my soul just to find it.

Shares