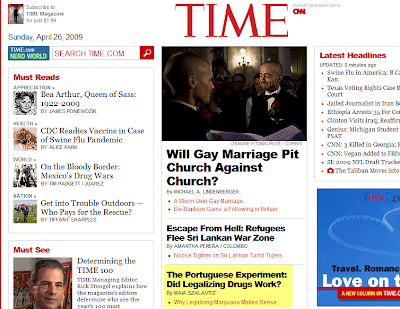

The report I wrote for, and last month presented at, the Cato Institute on the success of full-scale drug decriminalization in Portugal spawned a fair amount of media discussion -- in places such as Scientific American, The Wall St. Journal, The Vancouver Sun and many others -- but now, rather amazingly, Time Magazine has published a new article, by Maia Szalavitz, that substantively and impressively examines the report and its implications. Though the headline -- "The Portuguese Experiment: Did Legalizing Drugs Work?" -- is inaccurate (Portugal decriminalized, not legalized, drugs), the article itself (which Time is promoting with a fair amount of prominence) provides an excellent discussion of the unambiguous success of drug decriminalization and the impact which those findings ought to have on our own drug policy debates:

The paper, published by Cato in April, found that in the five years after personal possession was decriminalized, illegal drug use among teens in Portugal declined and rates of new HIV infections caused by sharing of dirty needles dropped, while the number of people seeking treatment for drug addiction more than doubled.

"Judging by every metric, decriminalization in Portugal has been a resounding success," says Glenn Greenwald, an attorney, author and fluent Portuguese speaker, who conducted the research. "It has enabled the Portuguese government to manage and control the drug problem far better than virtually every other Western country does."

Compared to the European Union and the U.S., Portugal's drug use numbers are impressive. Following decriminalization, Portugal had the lowest rate of lifetime marijuana use in people over 15 in the E.U.: 10%. The most comparable figure in America is in people over 12: 39.8%. Proportionally, more Americans have used cocaine than Portuguese have used marijuana.

The Cato paper reports that between 2001 and 2006 in Portugal, rates of lifetime use of any illegal drug among seventh through ninth graders fell from 14.1% to 10.6%; drug use in older teens also declined. Lifetime heroin use among 16-to-18-year-olds fell from 2.5% to 1.8% (although there was a slight increase in marijuana use in that age group). New HIV infections in drug users fell by 17% between 1999 and 2003, and deaths related to heroin and similar drugs were cut by more than half. In addition, the number of people on methadone and buprenorphine treatment for drug addiction rose to 14,877 from 6,040, after decriminalization, and money saved on enforcement allowed for increased funding of drug-free treatment as well.

Portugal's case study is of some interest to lawmakers in the U.S., confronted now with the violent overflow of escalating drug gang wars in Mexico. The U.S. has long championed a hard-line drug policy, supporting only international agreements that enforce drug prohibition and imposing on its citizens some of the world's harshest penalties for drug possession and sales. Yet America has the highest rates of cocaine and marijuana use in the world, and while most of the E.U. (including Holland) has more liberal drug laws than the U.S., it also has less drug use.

Those are just facts. After citing numerous recent events that indicate that a re-examination of our own drug policies is more possible than ever before (including the move in many states to legalize marijuana and the recent criminal justice reform bill introduced by Sen. Jim Webb), the Time article emphasizes the primary impact that the Portugal report ought to have:

At the Cato Institute in early April, Greenwald contended that a major problem with most American drug policy debate is that it's based on "speculation and fear mongering," rather than empirical evidence on the effects of more lenient drug policies. In Portugal, the effect was to neutralize what had become the country's number one public health problem, he says.

"The impact in the life of families and our society is much lower than it was before decriminalization," says Joao Castel-Branco Goulao, Portugal's "drug czar" and president of the Institute on Drugs and Drug Addiction, adding that police are now able to re-focus on tracking much higher level dealers and larger quantities of drugs. . . .

The Cato report's author, Greenwald, hews to the first point: that the data shows that decriminalization does not result in increased drug use. Since that is what concerns the public and policymakers most about decriminalization, he says, "that is the central concession that will transform the debate."

Few political orthodoxies have more of a destructive impact than our approach to drug policy. Our harsh criminalization framework results in the imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of American citizens, breaks up families, burns tens of billions of dollars every year, erodes civil liberties, turns our police forces into para-military units, and spawns massive levels of violence and criminality -- all while exacerbating the very harms it seeks to address. If a measured, rational debate over America's extremist drug policies can take place in Time Magazine, then it can take place anywhere.

Shares