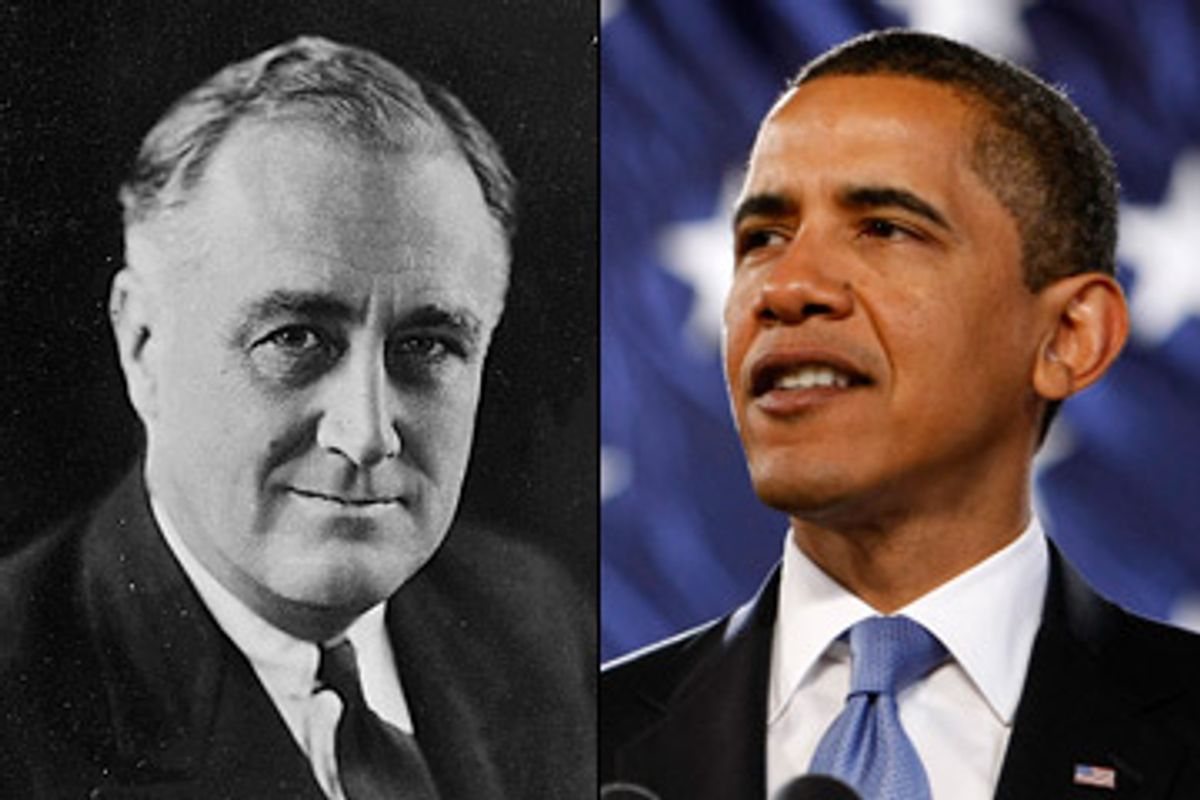

It is impossible to resist the temptation to compare Barack Hussein Obama's first 100 days with Franklin Delano Roosevelt's. Both men came to office at a time of great economic turmoil, when the circumstances of the day demanded immediate, drastic action. Both men projected a jaunty, cerebral, can-do aura of confidence and optimism. Both were Democrats with significant congressional majorities who came into power after an era dominated by Republicans. And both got to work immediately (although Roosevelt trumped Obama by skipping all the celebratory Inaugural balls.)

FDR's extraordinary record became the template against which all future presidents would be graded. Forget about the first 100 days -- in just his first two weeks, Roosevelt passed a farm relief bill, declared a banking holiday, and started the processes of ending Prohibition and taking the country off the gold standard. In the next three months, his administration launched the Tennessee Valley Authority, Civilian Conservation Corps, Public Works Administration, and FDIC. He signed into law the Emergency Banking Act, Federal Emergency Relief Act, Agricultural Adjustment Act, Federal Securities Act, and National Industrial Recovery Act. Altogether, he pushed through 15 major pieces of legislation.

Obama's first 100 days pales when compared with Roosevelt's. On the economic side, we have the stimulus bill, a housing plan, a budget and, notoriously, a bank-rescue plan that seems, at best, half baked. We see a great deal of effort expended attempting to salvage some kind of future for Chrysler and General Motors, and promises of action on the healthcare, education, and energy fronts. But we have, at this juncture, no idea how effective any of his initiatives will turn out to be. Compared with those of his post-WWII predecessors, Obama's 100 days are a dynamic display of activist government, but future historians will be unlikely to ooh and ah over them, as they do when contemplating FDR's.

Which is unfair, for several reasons.

The first and most obvious is that making direct comparisons across historical eras is a tricky business. FDR worked with a pliant Congress that was eager to do his bidding, not just because it was packed with Democrats, but also because the Republicans of the time had an entirely different conception of what their role should be at a moment of great national crisis -- and a considerably more amiable relationship with the new president. Take for instance, this quote from a Californian Republican, Hiram Johnson, (found via US News & World Report).

The admirable trait in Roosevelt is that he has the guts to try ... He does it all with the rarest good nature ... We have exchanged for a frown in the White House a smile. Where there were hesitation and vacillation, weighing always the personal political consequences, feebleness, timidity, and duplicity, there are now courage and boldness and real action.

Can you imagine those words coming out of Michele Bachmann's mouth? Or even John McCain's? Can you imagine a Hiram Johnson getting any airtime on Fox News today? From day one in office, Obama has faced a monolithically intransigent opposition, goaded by conservative media outlets who spend every hour railing against the socialist tendencies of the new occupant of the White House while dancing distressingly close to fomenting outright rebellion. There's just no comparison.

But it's also interesting to note that while, for example, Obama's cautious, incremental banking strategy is the polar opposite to FDR's quick and decisive actions to stabilize the banking system, Obama is outpacing FDR when it comes to fiscal stimulus. One part of the original Hundred Days that you don't hear too much about is the Economy Act of 1933, which aimed to balance the federal budget "by eliminating government agencies, reducing the pay of civilian and military federal workers (including members of Congress), and slashing veterans' benefits by 50 percent." The Economy Act reduced federal spending in 1933 by $243 million dollars, which is exactly the kind of thing most liberal Keynesian-oriented economists would view as utter anathema during an economic contraction. Imagine if Paul Krugman had been writing a column for the New York Times in 1933! He would have been outraged! Obama, in contrast, working through both the stimulus and the budget, has pushed through the biggest fiscal stimulus agenda in American history. FDR: You ain't got nothing!

Let's also recall that not everything FDR tried worked. The Economy Act, for example, did not succeed at balancing the budget because spending on other New Deal programs far eclipsed the savings generated from it. The central economic planning aspects of the National Industrial Recovery Act have been widely judged a failure (and the act itself was later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, as was the Agricultural Adjustment Act). Within the first Hundred Days and then for years afterward, Roosevelt proceeded in fits and starts, with lots of experimentation and policy reversals.

Future historians will no doubt look back at Obama's first 100 days and see numerous failures, too. But in the long run, if the Obama administration makes any real progress over the course of his entire administration in stabilizing the economy, reforming healthcare, and rebuilding our energy infrastructure, few people will care about what happened in the first three months of his first term. They will more likely observe that Obama, like Roosevelt, came into office with a determination to use government to remake society, rather than a predisposition to blame government for society's ills.

And that, ultimately, is where it is easiest to compare FDR's and Obama's first 100 days. Both presidents engaged wholeheartedly in an activist agenda, marking a dramatic sea change in the relationship between Americans and their government. Judging by Obama's poll numbers at the moment -- even if we do not know whether the initiatives he has launched so far will work -- most Americans seem pretty happy that he's at least trying.

Shares