"Revelation," notes the historian Barbara Tuchman in her epic book "A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century," "was the favorite guide to human affairs in the Middle Ages."

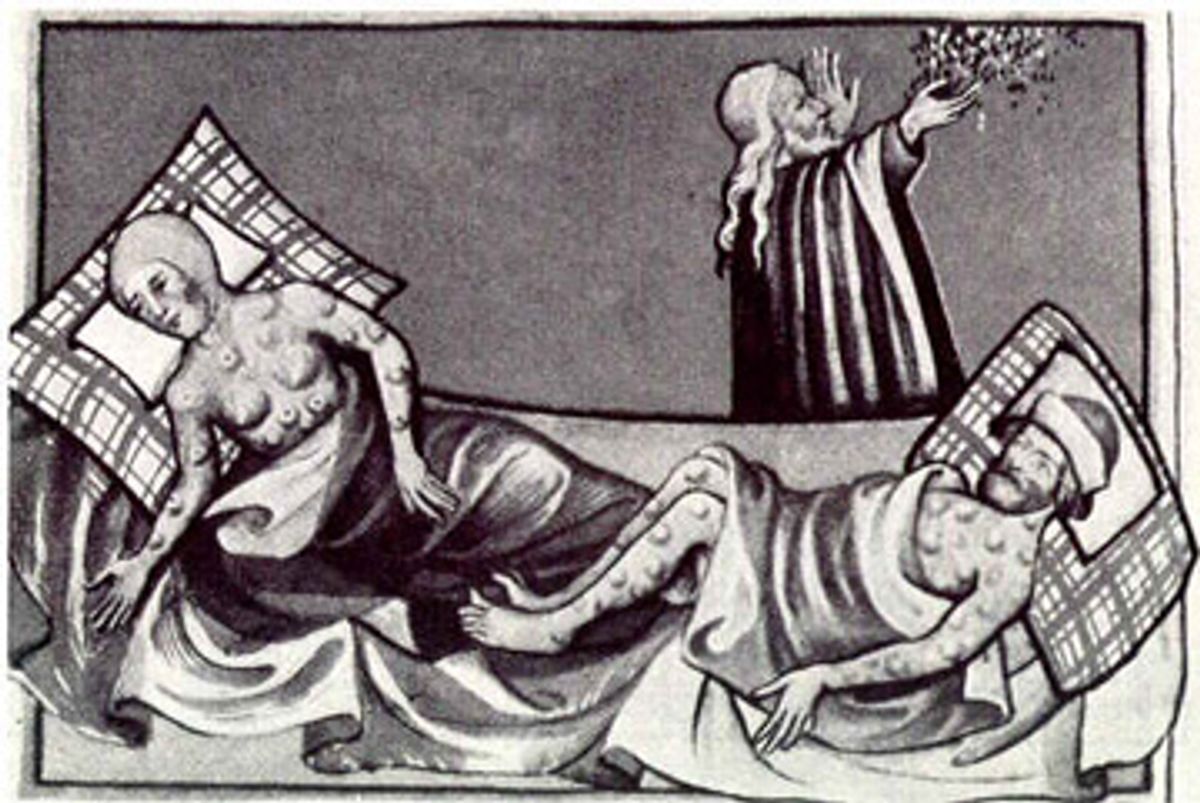

And the terrible predictions of Revelation seemed to have come to pass when, in 1347, a sinister, horrific malady began sweeping through Europe, cutting down nearly everyone in its ruthless path. In fact, the image of the Grim Reaper, a skeletal Death with a scythe, entered our iconography as a result of the most dreaded disease the world had ever known: the Black Plague. By the time it had done its dastardly work, the population of Europe had been so severely decimated that human life on every level, from personal and social to religious, political and economic, was forever altered.

The plague was so overwhelming and so relentless that medieval man had only one explanation for it: the wrath of God. It was compared to the biblical Great Flood and was seen as yet another attempt at divine housecleaning. People were convinced that, as in Noah's time, the human race was scheduled for destruction; more than one chronicler of the day sincerely believed that he was witnessing "the extermination of mankind."

But it was a more terrible extermination than any natural disaster. Victims were afflicted with horrible black swellings that oozed blood and pus, eventually dying -- within a few days -- from suffocation as a result of blood-filled lungs. And unlike the Great Flood, which came in one fell swoop and was gone, the Black Death was as mysterious as it was lethal. Nobody knew what caused it, nobody knew where it would next strike, nobody knew how to combat it. As a result, there was no time to marshal one's defenses. The plague was so deadly that people went to bed well, it was said, and died before waking, and doctors, infected at the bedside, would expire before their patients.

In Revelation, St. John predicted a plague that would cause "a third of the world" to perish. So medieval chroniclers assumed that this was the pestilence prophesied for the end of days, and proclaimed, without knowing actual figures, that "a third of the world has died."

They were not without reason in their assumptions; with actual mortality rates in villages, towns and cities ranging from 45 to 70 percent, life as anyone knew it literally stopped dead in its tracks. There was no food -- who was left to cut the wheat, mill the flour, bake the bread? Who was left to feed and milk the cows, butcher the cattle, tend to the horses? There was no work; every establishment was closed, its proprietors either dead or fled. There was no social life, for people feared each other most of all, as one's neighbor or family member might be the angel of death in disguise, carrying the disease to its next victim. Entire villages evaporated. "When the last survivors, too few to carry on, moved away," Tuchman notes, "a deserted village sank back into the wilderness and disappeared from the map altogether, leaving only a grass-covered ghostly outline to show where mortals had once lived."

It surely seemed as though God intended to wipe all traces of sinning humankind from memory. As one medieval chronicler wrote, "And people said, and believed, 'This is the end of the world.'"

- - - - - - - - - - - -

So. The world didn't end in 1347, or during the Great Plague of 1665, or in any of the other plague years. It didn't end in 1918, when the Spanish influenza pandemic, which operated in much the same way as the bubonic "yersenia pestis," went on a global killing spree that wiped out whole communities at record speed. It didn't end during the SARS panic of 2003, or with the avian flu scare in 2006. And chances are it won't end in 2009, with H1N1 stalking the earth.

In fact, with all the medical and technological advances in the 91 years since the 1918 global pandemic, we're considerably more prepared for this very moment -- the "next" pandemic that experts have been expecting for at least two decades. So, there's a good possibility that contraction of the H1N1 flu can be contained, and death tolls kept at a minimum. The point is, are we going to allow the very idea of a pandemic to create pandemonium? Or are we going to put on our thinking caps, settle down, and fight a "smart" war of vigilance and reason?

The word "pandemic" comes from the Greek "pandemos," meaning, "of all the people." It may not simply be coincidence that the word "pandemonium"-- uproar and noise -- comes right after it in the dictionary. Pandemonium was actually a literary location, chosen by Milton as the capital of hell in "Paradise Lost." Combine "of all the people" with the Greek "daemon" and you've got a chaotic situation instigated by evil spirits.

And how about the word "panic"? There's that "pan" again, although in this instance, it refers to that rambunctious Greek god Pan, whose chief talent seemed to be for creating fear and terror in lonely, isolated places. But while the word "pandemic" tends to push the panic button in most of us, it doesn't have to. At face value, a pandemic is only an epidemic over a large area. Not to be flippant with that "only," but as many medical experts have stressed in the past few weeks, a "pandemic" refers to the scope of a disease and not necessarily its severity.

If we look at what is actually happening, at this very moment, with H1N1, we have to admit not only that things are not all that bad, but also that they have, in many instances, been blown totally out of proportion. Just today, the Mexican government reported that the suspected confirmed cases of deaths in that country due to the disease are half of what the world had been led to believe and that the spread within the country has stabilized. So far, no one anywhere else has died, with the exception of the poor Houston toddler who contracted the virus in Mexico, and not everyone who is in close proximity to an infected person gets sick. And, those who do contract H1N1 tend to have mild symptoms that resolve themselves without prescription medications.

Sure, there are more than 100 confirmed cases of H1N1 throughout the U.S., and this number will undoubtedly have risen by the time this article is published. But in a population of more than 300 million, that's an awfully small segment to cause a pandemic of global hypertension, especially when the disease is in such a mild stage and is eminently treatable; the everyday flu strikes far more people; and most experts predict that this particular strain will soon be on the wane over the summer months, probably resurfacing with more virulence in the fall and winter. And by then we may have a vaccine to fight it, in addition to the antivirals that have so far been effective against it.

It sure doesn't help when people like Dr. Margaret Chan, the World Heath Organization's director-general, declare that "all of humanity is under threat," even though WHO's rationale is that this is just a warning to every country to step up preparedness, rather than a trumpet call to pestilential Armageddon. Which raises the question, is Chan simply being honest, practical and proactive? Or is she our modern-day Pan, striking terror in places both lonely and overpopulated throughout the globe?

I am no doctor, and am certainly not in a position to take on the World Health Organization or Chan, whose qualifications are exceedingly impressive and who understandably considers it her duty to keep the world informed of potential danger. But look what's going on: People are running out to get face masks that the experts tell us won't make a bit of difference. Countries are slaughtering pigs and banning pork products even though we know you can't get "swine" flu from eating pork. The talk radio fascists are having a field day, screaming that we're under a biological terror threat from Mexico. Hundreds of schools are closing because one student in a district tests positive for H1N1 and probably never even gets sick enough to go to the hospital -- all of which creates untold hardship on working families and is sending kids out on a big holiday to the malls, movie theaters and the other places they aren't supposed to be. I think it might be time to ask ourselves if we haven't gone just a little overboard.

Yes, this flu can, and probably will, return in six months, with or without a vengeance. Yes, many more people could die from it. But the worst hasn't happened yet, and as long as we wash our hands throughout the day, don't pick our noses, sneeze and cough in our elbow pits, take our Tamiflu and say our prayers, we just might come out alive. Provided we don't turn a pandemic into pandemonium.

Shares