One summer night in 1985, near the beach in the Long Island resort town that gives Colson Whitehead's "Sag Harbor" its title, Benji, the novel's awkward, African-American teenage hero, sees a firefly. Millions of those living symbols of ephemerality are glimpsed by millions of kids across every American summer, but this one gets Benji thinking.

"A black bug secret in the night," he tells himself. "Such a strange little guy." The firefly gets its name from "people time, when in fact most of its business went on when people couldn't see it," Benji reflects. "Its true life was invisible to us but we called it firefly after its fractions ... It was a bad name because it was incomplete -- both parts were true, the bright and the dark, the one we could see and the other one we couldn't."

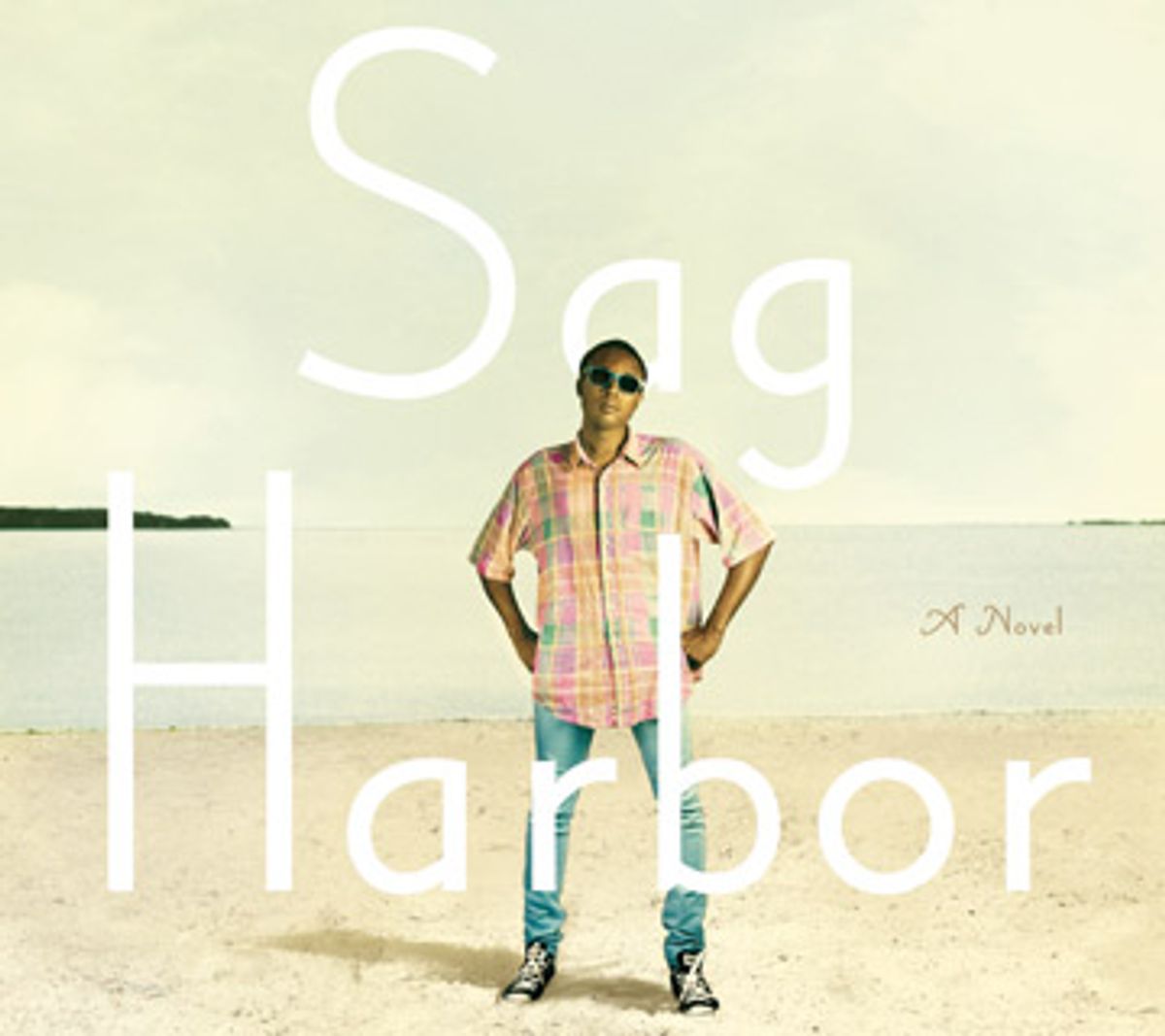

This is one of the moments in "Sag Harbor" when we feel its supremely gifted and elusive author showing his face through the deadpan self-mockery and digressive anecdotes of Benji's personality. If anyone in this book should be described as a strange little guy and a black bug secret in the night, half visible and half in darkness, it's the Siouxsie and the Banshees-listening, Chuck Taylor-wearing misfit protagonist and narrator.

As Whitehead is surely aware, if the social setting of "Sag Harbor" -- the closed world of an all-black summer enclave on Long Island's ritzy East End -- is distinctive, the novel nonetheless belongs to a hallowed literary genre, the quasi-nostalgic summer flashback that mixes comedy and heartbreak, pop songs and ice-cream cones. In point of fact, those ingredients are all present: Benji learns to drink beer, kisses a girl for the first time and begins to grasp how screwed up his parents' marriage is. He slings gourmet ice cream at the Jonni Waffle, guiltily indulges in Carpenters and Kenny Rogers hits on WLNG, the East End's notorious easy-listening station, and triumphantly attends a concert by UTFO, a gimmicky rap act whose hit that summer (and only hit ever) was the song "Roxanne, Roxanne."

It won't surprise readers of Whitehead's arch and trans-generic earlier books, including the parahistorical elevator-repair mystery "The Intuitionist" and the all-too-realistic journalistic satire "John Henry Days," to learn that "Sag Harbor" is both a genuinely sweet and sad summer-nostalgia novel and a self-conscious, almost meta-version of one. As Benji observes late in the story, the cheesy tear-jerker pop songs played on WLNG were designed to induce "a deep sense of familiarity and loss" even if you had no special association with them, and you'd heard them the first time while you were searching through the sock drawer or wiping tartar sauce from your lip. They provided "a feeling of nostalgia for something that never existed." Whitehead is daring us, by implication, to feel the same about his book.

By design, there's not a hell of a lot of plot here. "Sag Harbor" hopscotches around a little in time and place, occasionally drawing anecdotes from Benji's childhood, or from his life during the other three seasons as a Manhattan apartment kid who attends a predominantly white private school. But it basically just follows Benji -- who longs, fruitlessly, to be known as Ben -- across that summer of '85, from his family's arrival in Sag Harbor very early one June morning right through to an especially disastrous Labor Day barbecue and bonfire. (I feel really bad about what happened to the Gardners' patio furniture.)

This results, slowly but surely, in a lovingly constructed social portrait of the insular world of black Sag Harbor, a seasonal community of African-American strivers and success stories -- doctors, lawyers, teachers, preachers and undertakers -- whose roots stretch back at least to the 1930s. Whitehead has said that "Sag Harbor" is autobiographical, and he did indeed spend his childhood and teenage summers there. He writes with deep, Scott Fitzgerald-esque knowledge and passion about the heritage and tragedy of the place, about its heartbreaking adoption of "Ain't No Stoppin' Us Now" as an anthem, about how it retains its grip on the souls even of those who don't "come out" for the season anymore, who have suffered through bankruptcy or bigamy or divorce and allowed their houses to sit shuttered for years on end or, far worse, have sold them to strangers.

But while the plotless, summery forward motion of "Sag Harbor" does possess a tremendous, atmospheric, fugue-state power, it also poses problems for the reader. The overall effect is something like combining the first few chapters of "Swann's Way" with John Updike's teenage-summer story "A&P," spinning them out to almost 300 pages and adding a black kid who plays Dungeons & Dragons as the narrator. Characters and themes appear and are presented in a fashion that makes them seem important, and then recede again. We wait for them to be resuscitated and assume their expected symbolic roles in the story and they never do, leaving us to wonder what to make of the novel's apparently deliberate lack of focus. Or, more simply, to wonder what in hell it's really about.

I suppose it fits with Whitehead's narrative voice -- which is dry, funny and easily distracted, only to explode into unexpected lyrical passages -- that he asks us to decide what we find important in Benji's summer, rather than be told. Is this a family novel? Well, Benji's drunken and abusive father, with his perverse radio tastes (lite-rock or Afrocentric talk) is a vivid character, but he makes only sporadic appearances. Benji's mother is less vivid, and his older sister only shows up once outside an East Hampton club with some Eurotrash-looking guy.

The younger brother is a member of the crew Benji rolls around Sag Harbor with, upper-crust city kids striving to be "down" because the color of their skin dictates that they should be. Some percentage of "Sag Harbor" is a frequently hilarious, sad and profane chronicle about these uneasy teenage boys, caught between a disapproving older generation, the unforgivable crime of "acting white" and the sudden shift toward criminal hardness in '80s black male culture.

With his taste in indie rock and comic books, and his Jewish stoner buddies from school, Benji is a near-outcast even in this Sag Harbor group. At least until he realizes, watching two of his friends hopelessly bungle a complicated street handshake, that all the black kids here are faking it. (Whitehead includes a helpful chart for constructing period-appropriate insults built around a modifier, a gerund, an object and a nonsensical kicker, e.g., "You fuckin' Gorbachev-lookin' motherfucker, with your monkey ass.")

One could argue that the idiosyncratic and tragicomic nature of race in post-civil rights America has always been Whitehead's primary subject, but that is to diminish him to a black-hipster signifier rather than an eccentric, original and sometimes frustrating voice. "Sag Harbor" is wonderful without being completely successful. It's both a communicative and a performative work, one that tries to capture the magical details of a place and time and the eternal teenage angst of shoveling out two scoops to "those deposited by helicopter, those who putt-putted down 27 in jalopies, those who blessed the Earth with every footstep, those who deigned, those who stooped to, those who would get their pictures next to their obituaries in the Times and those who would lay on the floor of their abject rooms for days before being discovered."

This is a book that invites you to see that its author belongs to a people and a town and an era, as do we all, but that while he honors those things they do not encompass him and never did. Race and community and nation are schemes we all use to mitigate our essential loneliness, but it persists and at some point we find ourselves alone in our late summer beds, like Benji at the end of "Sag Harbor," imagining a better future. Strange little bugs, keeping secrets in the night.

Shares