When Barack Obama removed George W. Bush's ban on federal funding for new embryonic stem cell research in March, the president cast his decision as part of a larger effort to remove politics from science. No longer would research, Obama said, be shackled by a "false choice between sound science and moral values."

It turns out the president cannot separate politics and science so easily. No sooner had Obama issued his order than conservative lawmakers in state legislatures began proposing new restrictions on embryonic stem cell research, ranging from criminal penalties to bans on state-level funding. In fact, Obama's decision has emboldened conservatives to increasingly link stem cell research to abortion. Far from conceding the issue, they are in it for the long haul.

But the stem cell battle is not just a high-profile clash of values. The dispute provides a sharp focus on how science may help reshape America. Several states have set aside billions of dollars to support stem cell research, and the new federal money Obama is promising will generally flow to those areas. That means states supporting stem cell research will experience an economic windfall while attracting highly educated technology workers who tend to vote Democratic. The more conservative states restricting stem cell research will attract fewer funds and fewer socially liberal voters. In short, a state's stem cell policy will influence electoral results and help determine whether a state turns red or blue.

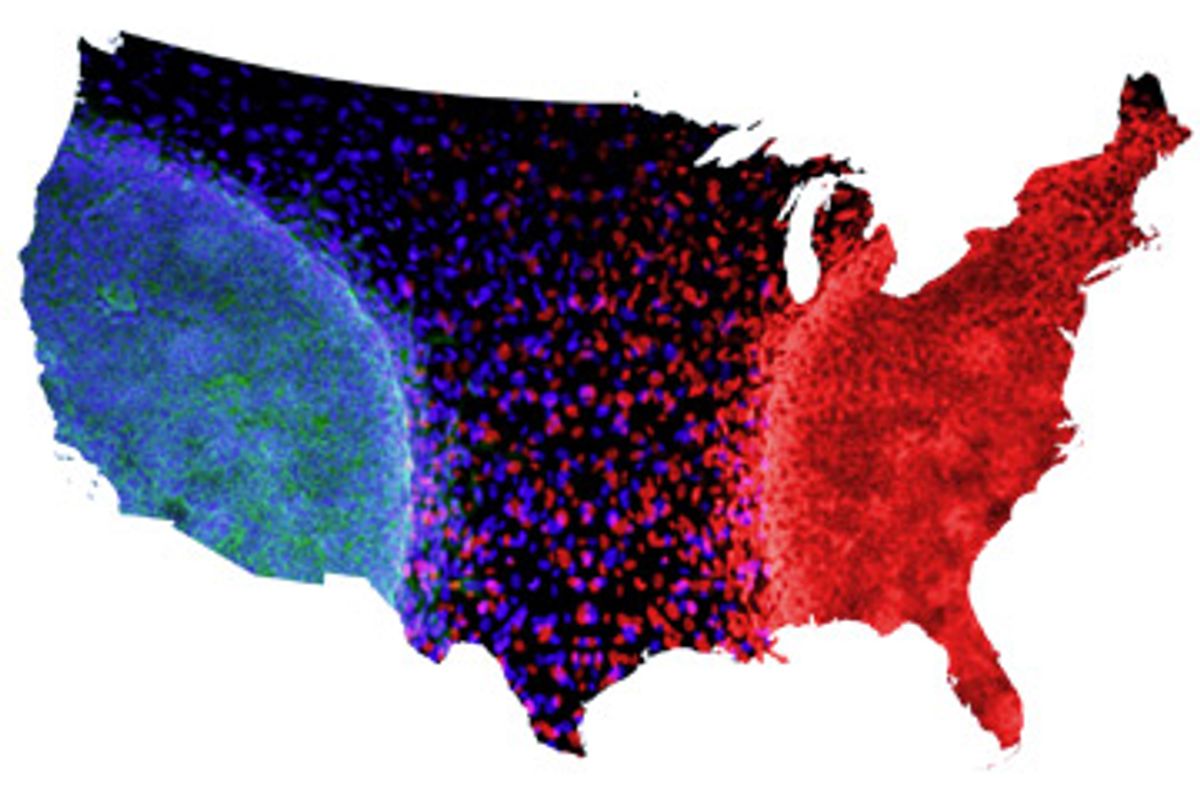

At the moment, stem cell science mirrors November's electoral map. Twelve states allow the use of public money to fund stem cell research -- and Obama won them all in 2008. Four states have moved to either restrict stem cell research or limit public expenditures for it since Obama's announcement -- and they all voted for John McCain. But now that map could change.

In stem cell politics, key battlegrounds include Georgia, Texas and Arizona -- red states where Obama and the Democrats made inroads. These are places that have significant academic and scientific infrastructures but that Republicans control politically. Restrictions on science there could slow the kind of economic growth associated with Democratic support. At the same time, the GOP is putting its popularity at risk by curbing research that most voters support. The new regional political dynamic of the stem cell war is set.

Most cells are specialized. Your various forms of white blood cells fight illnesses, while red blood cells help oxygen circulate in the body. Stem cells are unspecialized, waiting to be assigned roles. If we could give stem cells the right biological instructions, we could use them to repair damaged body parts such as heart muscle cells, limiting heart disease.

Adult stem cells help maintain a particular bodily organ or tissue. The brain has its own reserve supply of adult stem cells. But embryonic stem cells have not yet been directed to a particular body part, increasing their potential value. They might help fix any organ or tissue.

Extracting the stem cells from a days-old embryo, usually acquired from an in vitro fertilization clinic, destroys the embryo. Many scientists have argued that since clinics produce more embryos than they use, employing the remaining ones for medicine is ethically justified. But stem cell research opponents disagree and have responded by trying to alter the practices of fertility clinics.

In 2007, researchers announced the development of induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs) in humans -- adult cells reprogrammed to mimic embryonic stem cells. In theory, IPSCs could bring the political battle over stem cells to an end, since producing them does not involve embryos. But many scientific hurdles remain to be cleared before IPSCs can be considered a safe and complete replacement for embryonic stem cells.

In 2001, Bush announced a ban on federal funding of embryonic stem cell research, except for work on a limited number of already existing stem cell "lines." Since then, 12 states have funded stem cell research themselves. California's program, at $3 billion, is the biggest. The state aims to build a dozen stem cell facilities at universities and other research institutes and says it has awarded more than $600 million in research money so far.

The overall economic impact of the biotech industry is even greater than the numbers suggest, as industry earnings create a "multiplier effect" that ripples through a local economy. In California, such activity includes the construction workers building the new Mission Bay research facility for the University of California at San Francisco, and the service industries that grow around well-paid technology workers. A 2004 Milken Institute report estimated that every biotechnology job in California creates an additional 3.5 jobs. In 2003, industry earnings in California totaled about $5 billion but created about $21 billion in overall economic output.

States not investing in stem cell science are missing out on this bonanza. Not only is this part of biotech economically regenerative, but it's also popular. A 2007 Gallup Poll showed that by a 64-to-30 margin, Americans think embryonic stem cell research is "morally acceptable." But social conservatives such as Oklahoma state Rep. Mike Reynolds, disagree. Reynolds introduced a bill making it a misdemeanor to conduct research on embryonic stem cells. "I am a pro-life candidate, and I believe life begins at conception," Reynolds says.

In Georgia, a bill under consideration would put limits on both stem cell research and in vitro fertility clinic practices. "A person is a person no matter how small," says Dan Becker, president of Georgia Right to Life. "There is a paradigm shift going on, a shift toward personhood. You're going to see more states adopt that strategy." Indeed, bills in Texas and Mississippi would bar state funding for embryonic stem cell research. Arizona is among the states already featuring similar laws.

But Georgia best exemplifies the political and economic issues at stake. The state "is a prime example of the legislative revolt as a result of Obama's executive order," says Patrick Kelly, director of state government relations at Bio, an umbrella group representing biotechnology firms.

Georgia may be red on electoral maps, but in November, Obama lost to McCain there by a mere 5 points -- the best showing by any Democratic presidential candidate, apart from Southerners Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter, since 1960. Democratic challenger Jim Martin forced incumbent Republican U.S. Sen. Saxby Chambliss to a runoff with a 3-point loss, although Chambliss' subsequent 15-point victory shows that a real gap still exists.

In March, the Georgia Senate passed a stem cell bill that limits new embryonic stem cell research and prevents couples who use in vitro fertilization clinics from authorizing the destruction of their own remaining embryos. The state House of Representatives may take up the bill in the fall. The measure shows how conservatives are linking stem cell research to abortion by promoting the "personhood" of embryos.

"We've been good at spinning many antiabortion scenarios," Becker says. "What we've failed to do is personalize the embryo issue. We're shifting and attacking the position that in the first trimester this is nothing other than a medical blob. This is a human being." Georgia Right to Life has created television spots to reinforce the message.

The bill's opponents emphasize their own moral interests. The legislation "would tell patients that we are not interested in helping them," says Charles Craig, president of Georgia Bio, which is lobbying against the bill along with various patients' rights organizations.

As far as the economic consequences, Craig believes that "if Georgia were to restrict science considered legal and ethical by the federal government, it would send a message that Georgia is out of step, and possibly anti-science and anti-technology."

Biotech backers want to develop the state's Innovation Crescent, running from Atlanta to Athens, which features research universities including Georgia Tech, Emory and the University of Georgia. The state's life science industry has grown 140 percent since 1993, although the state lags in some measures. While ninth in population in the U.S., Georgia ranked 22nd in the number of biotech workers in 2003.

Stem cell research can be funded in at least four ways: federal funds, state money, private gifts and venture capital. Banning state funds eliminates only one income stream. But that can lead to substantial economic disparities. In 2006, New York's state agencies, which are vigorously pursuing biotech growth, spent about $100 million more on scientific research and development than did Georgia's, nearly five times as much per capita.

State funds attract additional research dollars, magnifying these discrepancies. One modest piece of legislation in California, the Roman Reed Spinal Cord Injury Research Act, named for a young man who was paralyzed playing football, authorized $12.5 million in state funding -- but garnered $50 million in matching grants.

"There's a huge push-pull effect," says Don Reed, Roman Reed's father, who is now vice president of Americans for Cures, a stem cell research advocacy group. "If I were running a state, I would not wait to set up a funding program. It's going to help their economies."

Kelly agrees. "Places that have put in place stem cell programs also have more scientific infrastructure and an indigenous research community," he says. "And they will continue to lead the charge because they're that much further ahead."

On the other hand, state funding bans can be both a symbolic and a tangible deterrent to scientists -- and hinder a state's economy. In a 2005 Science paper, researchers Joanna Kempner, Clifford Perlis and John Merz found that scientists pursuing controversial research feel cornered not only by formal restrictions -- like funding laws -- but also by social pressures. "Informal limitations are more prevalent and pervasive than formal constraints," they write.

Texas-based journalist Bill Bishop, coauthor of "The Big Sort," a book about the social polarization of America, has discussed the problem of social stigmatization with Houston-area scientists. "They were saying, 'I don't want to live some place where I'm considered immoral,'" Bishop says. "They pick up these signals and they don't want to work in a setting where they will feel shunned." Likewise, Craig suggests, "If Georgia is singled out as a state restricting this research, it could give scientists pause about coming here."

Stem cell opponents, in Georgia or elsewhere, are unconcerned with economic fallout. "I have no interest in supporting the economy of murdering unborn children," says Reynolds, the Oklahoma legislator.

But if state support for stem cell science makes an economic difference, does it matter at the ballot box? Although scientists and technology workers are hardly a unified voting bloc, expanding a regional science community seems to increase the number of educated, socially liberal voters. And that helps Democrats. In the 2008 election, 17 percent of the electorate had attended graduate school, and those voters supported Obama by a 58-40 ratio, compared to his overall 53-46 margin of victory.

Most likely, highly educated voters have already colored the electoral map in North Carolina, poster child for biotechnology growth. In the Raleigh-Durham area's Research Triangle, local leaders have aggressively recruited biotech firms and promoted the region's universities as sources of intellectual capital. In the state, Obama beat McCain by 13,692 votes, but won the 13 self-identified Research Triangle counties by 145,498 votes. That's over 100,000 more than Bill Clinton's Research Triangle margin in 1992. And while more than one factor explains this increase -- high turnout, student vote -- North Carolina's high-tech growth surely helped turn the state blue in 2008.

"If you look at where states are growing, it's the urban areas, and clearly technology plays a leading role," says Ruy Teixeira, coauthor of "The Emerging Democratic Majority." "Biotechnology is one of the things that create growth, with implications politically. The effect is that it will make those areas more progressive." Georgia could follow the same general pattern. "I don't think it's far out of reach," Teixeira says, citing the potential for economic changes in the Atlanta area. "That's going to be the ground where a shift takes place." It certainly has room to grow. Georgia is slightly bigger than North Carolina in population, yet according to the Milken Institute numbers, the biotech business accounts for only about 17,000 jobs in Georgia, compared with 127,000 jobs in North Carolina.

To be sure, there are only so many biology Ph.D.s out there who vote. "The question is, What gets you from tens of thousands of high-tech voters to a larger change in voting patterns?" says Andrew Gelman, director of the Applied Statistics Center at Columbia University and coauthor of the book "Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State." One prominent type of answer comes from economic theorist Richard Florida, who believes information-age cities are magnets for "creative class" workers, perpetuating a blend of high-tech growth and social liberalism. Teixeira calls these places "ideopolises."

Biotechnology's future jobs will also be filled by the young, who trend heavily Democratic: Obama won the 18-to-29 age group by a 66-32 ratio. Georgia has a young population, although the creative-class thesis holds that such workers follow jobs across the map. In Texas, there is a potent research infrastructure, albeit in a large state, and multiple institutes have started stem cell research in recent years. These include the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, the Heart Hospital of Austin, and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas, among others. But according to the Milken survey, the state had just one-third the biotech revenue of North Carolina.

Arizona seems like another Democratic target. Obama lost by just 8 points on McCain's home turf, and Janet Napolitano was a popular Democratic governor. Today, Arizona State University, in traditionally GOP-friendly Maricopa County, has been attempting a huge science-based expansion. But the state's embryonic stem cell research ban may be one reason it is in the lower half of the national rankings in biotech revenue. That is a continued roadblock in a state that Democrats find tantalizing in electoral terms. "Maricopa County used to be strongly Republican," Teixeira says. "If Democrats get close enough to win there, they can win in Arizona. Texas is a little further away."

Purple-shaded Missouri, which allows but does not fund embryonic research, is another state to watch. And the battleground states that Obama happened to win, which also fund stem cell science -- Florida, Ohio, Virginia, even Indiana -- remain highly contested, meaning the Democrats could benefit from further creative-class development.

The stem cell skirmishes epitomize the problems that Republicans are having as they grapple with the future. For now the GOP is reaching into its old playbook, trying to energize its base through cultural politics, with no guarantee that the stem cell debate will take place on their terms. "Stem cell research is popular," Gelman says. "That's where the Democrats want the battle to be. The Republicans want the battle to be about abortion." State-level politicians from conservative districts may be staging a rear-guard action that displeases the larger public -- and many Republicans nationally. A Gallup Poll from February, just before Obama's stem cell decision, showed 39 percent of Republicans agreeing that embryonic stem cell research restrictions should be eased or eliminated.

Wedge issues are supposed to split the other party, not your own. Currently the GOP's stem cell opposition seems more like an effort to forestall the kinds of social and economic changes that help Democrats, instead of providing a way forward for Republicans. Indeed, to consider the deep limitations of the GOP's position, ask one question: What if stem cell research does create a major breakthrough? "If stem cells provided a cure for juvenile diabetes, this issue would be a whisper in the wind," says Kelly. For now the battle continues, but it's clear which way the wind is blowing.

Shares