President Barack Obama is famously much better at playing basketball than at bowling. But to succeed in the Middle East, he needs to be good at a different game altogether: golf. There are no fast-paced victories to be had here, no dunks, no three-point shots. As in golf, the sand traps and roughs are treacherous and the course is slow, and there is time for players to quarrel and throw their irons about petulantly. Above all, as in golf, the secret of a good swing is a strong follow-through.

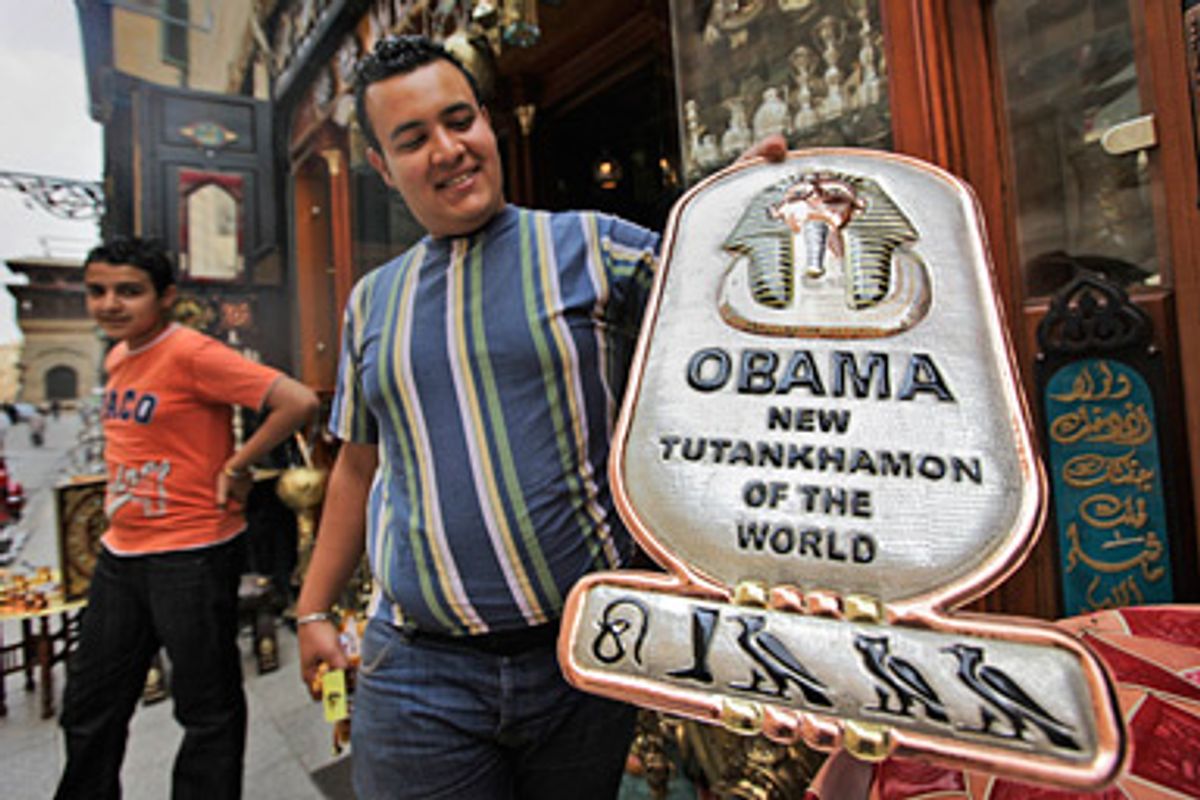

Obama, who begins a trip to the region Wednesday, starts his term much more popular in the Middle East than his predecessor, George W. Bush. Last year, in many Muslim-majority countries, including U.S. allies such as Turkey, Bush often had favorability ratings in the single digits, neck and neck with Osama bin Laden. In contrast, a new opinion poll released by the Brookings Institution shows that in six Middle Eastern states, Obama comes in at 45 percent favorable, and if Egypt is subtracted, the proportion soars to 60 percent. As Obama prepares to make a major address to the world's 1.5 billion Muslims, can he capitalize on his rock-star status in Riyadh and Beirut to go beyond celebrity glitter to concrete achievements that would benefit both the United States and the Muslim world?

The Brookings poll shows that just three issues are cited by most Arab respondents as determinative of their view of the United States. In order, they are Iraq, the plight of the Palestinians, and attitudes toward the Arab and Muslim worlds. Interestingly, the war in Afghanistan, democracy promotion, and the issues around Iran have very little resonance among Arab publics. Iraq was cited as the key issue by 42 percent in six countries polled, so it is fair to conclude that Obama's stock in the Arab world, at least, is likely to rise or fall on how well he handles his planned military disengagement from that country.

The truth is that Obama's task in the Arab world is more difficult and more important than elsewhere. He is wildly popular in Indonesia, the world's most populous Muslim nation, where he spent some of his childhood and from whence hailed his stepfather. Likewise, West African Muslims overwhelmingly supported his presidential bid last year. The U.S., however, does relatively little trade with either region, and they have not traditionally been central to its foreign policy. The 325 million Arabs are a minority of Muslims worldwide (and not all Arabs are Muslim), but Arab Muslims are disproportionately influential among their co-religionists and, because of their energy resources and strategic position between Europe and Afro-Asia, are especially important to the United States and its allies. They are the Muslims who are most skeptical about Obama.

Obama will begin his Middle East tour with a visit to Saudi Arabia, a move warmly greeted by Saudi Op-Ed writer Abdul Malik Ahmad Al-Sheikh. The latter noted that Saudi Arabia is the holy land for Muslims, the site of the sacred cities of Mecca and Medina, while Egypt has been a center of pan-Arab nationalism. Obama's itinerary thus honors both the key religious and political symbols for Arab Muslims. Al-Sheikh glowed, "The step you are taking also comes to honor what you promised the day you were sworn in as President of the United States of America, a day on which you extended your hand to the Islamic world, something which was not done by any American President before you." Pleading for an end to the oppression of the Palestinians, he quoted Alexander Hamilton to the effect that "the sacred rights of mankind" cannot be found in old parchments, but are rather "written, as with a sun beam, in the whole volume of human nature, by the hand of the divinity itself." Al-Sheikh concluded that the American founding fathers agreed that rights are "Allah-given."

His next stop, Egypt, is perhaps the toughest room for the president to work. Obama faces the difficult challenge of convincing the sullen Egyptian public that the U.S. does not covet Arab land and resources, and that it can be an honest broker between the Israelis and the Palestinians. Along the Nile, anger toward Israel, in the wake of the Lebanon and Gaza wars and ever-expanding Israeli settlements in the West Bank, is probably higher than at any time since the 1970s. Public opinion is even more negative in Jordan, but there are 20 Egyptians for every Jordanian. Egypt is the most populous Arab country, with a third of the total Arab population, and it is an important political and cultural center. These are the reasons Obama chose it as the venue for his speech.

Washington has a poor track record when it comes to listening to its Arab allies about the realities of their region, and Arabs know it. Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak had warned George W. Bush against invading Iraq and predicted that such a rash action would produce "a hundred Bin Ladens." Despite being a putative American ally, Mubarak praised the Iraqi army that fought invading U.S. troops as brave defenders of their homeland. Many Egyptians see the U.S. presence in Iraq as a Western occupation of Arab land, and they take it personally.

Egyptian political commentator Nael M. Shama spoke for many of his countrymen when he warned that good intentions and sweet talk would not take Obama very far. He wrote, "The Arab world is expecting concrete steps on the part of the world's only superpower to address the region's real problems, particularly the six-decade Arab-Israeli conflict. Thus far, the change in U.S. foreign policy has been in style, not substance." Seventy-five percent of Egyptians said last winter in a BBC poll that resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict should be Obama's No. 1 priority (the Gaza war had just begun as the poll was being conducted). More recently, Egyptians see the withdrawal from Iraq as even more pressing. Shama concluded that most likely, the U.S. special relationship with Israel would derail new peace moves and further sour U.S.-Egyptian relations, despite the best of intentions on Obama's part.

Al-Sheikh, the Saudi opinion page writer, is more hopeful than his Egyptian colleagues, despite recognizing the profound obstacles to progress. He said, "The peoples of our region dream that their area will be free of weapons of mass destruction, and free of the reasons for violence and counter-violence." Recognizing that any steps Obama initiated along those lines might not be accomplished in one term or even two, he nevertheless urged that a beginning be made. Among persons of good will, "according to a new vision, the motto of which would be your motto, 'yes we can.'" He concluded, "We say welcome to the President, Barack Obama, in the land of Islam and of peace."

Whether Shama's pessimism or Al-Sheikh's optimism proves more warranted depends on whether the president has that all-important follow-through.

Shares