Acts of madness like the killing of George Tiller and Stephen T. Johns can be too easily dismissed as the work of disturbed individuals and then subsumed in the usual rumble of recrimination between left and right. But if we are to understand the deeper implications of those acts of murder, what must be examined is their origin in the shadow world of white nationalism.

Nobody knows more about the movements that spawned the alleged gunmen than Leonard Zeskind, who has spent most of a lifetime observing, analyzing and opposing racism and anti-Semitism in America and abroad. Now he has distilled those hard and dangerous decades of work into "Blood and Politics: The History of the White Nationalist Movement From the Margins to the Mainstream," a magisterial new book that explains how and why racial hatred became and remains a significant political force in American society.

To Zeskind, the most recent attacks only represent the latest stage in a long wave of extremist violence dating back to the early 1980s, marked by assassinations, bombings, bank robberies and other crimes that were largely ignored by the mainstream media because they often occurred in distant rural locations. "The reason we're talking about this incident," he said "is because it happened in Washington, D.C., at the Holocaust Museum, instead of somewhere in the backwoods of Montana."

According to Zeskind, "the level of racist and anti-Semitic violence was much worse during the Reagan era, back in the '80s, when we had the Order, which killed [Jewish radio host] Alan Berg, and certainly in the '90s when Clinton was president, when we had Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City bombing, the Aryan Republican Army robbing banks, the Phineas Priesthood shooting people. Those years saw much more of these kind of attacks than what we are seeing right now."

That distinction is no excuse for complacency, he emphasizes, because there may yet be worse to come in a period of economic privation and social change. "What we are seeing is the first spate of violence since the crackdown after Oklahoma City, when the government went after these criminals, rounded up all the shooters that they could and prosecuted a lot of them." Effective prosecutions conducted by the Clinton Justice Department suppressed the most violent wing of the white nationalist movement, as did the national alert against terrorism that followed the 9/11 attacks.

"A bunch of the violence-prone people got arrested in the period between 1997 and 1998," he recalls with satisfaction. "The government went after them like nobody's business, and Clinton did a good job of isolating them. Then Bush's rhetoric about terrorism put a damper on them, because they knew the Department of Homeland Security was looking at them." Now it may well be time for the government to devote additional intelligence and investigative resources to domestic extremists.

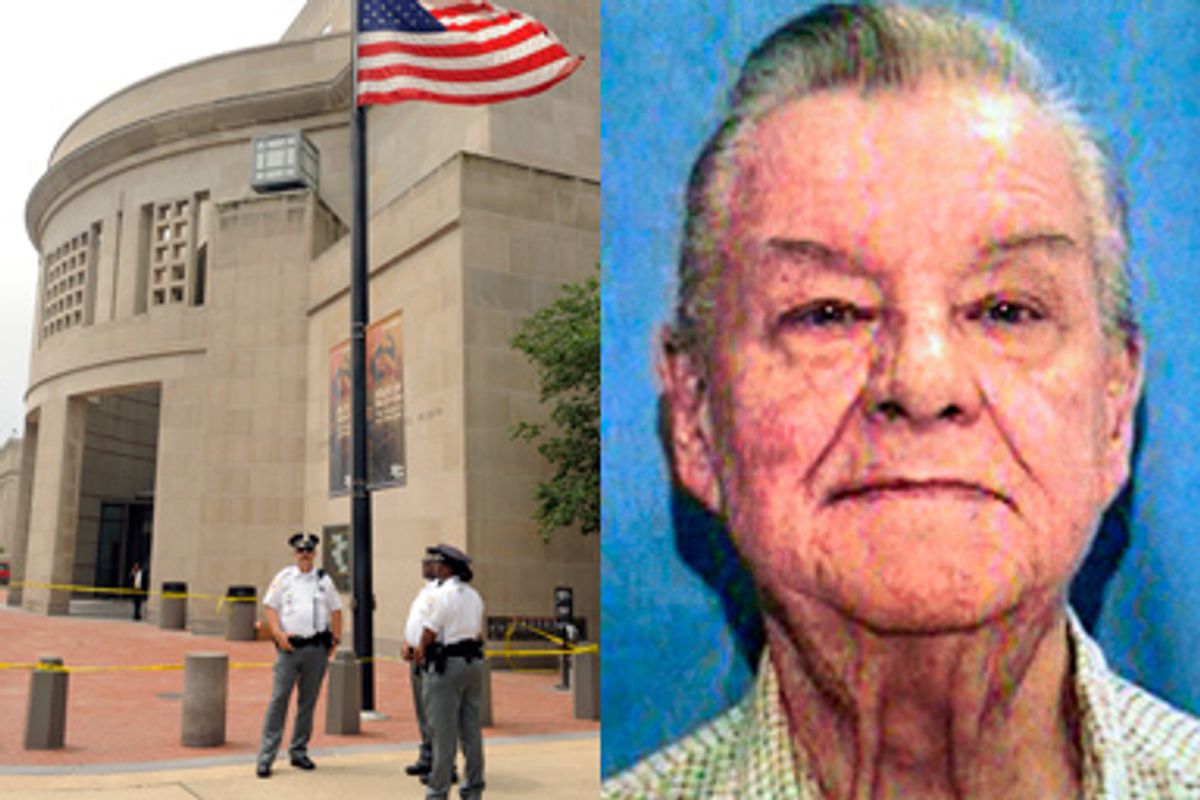

But Zeskind dismisses, sardonically, the notion that the shootings of Tiller and Johns are "somehow Barack Obama's fault" -- for simply being the first black president, a symbol of racial equality and the child of a black man and a white woman. He points out that both of the men arrested in these shootings -- antiabortion zealot Scott Roeder and anti-Semitic pamphleteer James von Brunn -- were active extremists long before Obama's election. Indeed, years before Obama first ran for office, Roeder was reportedly involved with the Freemen, a white supremacist sect that promoted Christian Identity ideology, while von Brunn had worked with the pro-Nazi, Holocaust-denial movement for as long as 40 years. "Obama simply confirms their belief about what has already happened, namely that the United States government is in the hands of their racial enemies," Zeskind says." But they had that belief long before the 2008 election."

As in "Blood and Politics," he warns against the comfortable liberal assumptions about the mentality and intelligence behind acts of crude violence. "If you want to understand the threat, don't substitute what you think about these people for what they think about themselves." He notes that like many of the leaders of the white nationalist movement, von Brunn was in no way stupid or unsophisticated. Attributing his behavior to mental illness is a way of ignoring the underlying issues that make such individuals dangerous.

"Von Brunn may have had mental problems but he really had serious political problems -- and in that sense he wasn't alone. This was a guy who wanted the old white republic that used to exist in America. He thought the Jews had stolen it from him. People like him don't want to share power. When they see any gains by people who are not part of their group, they cannot tolerate it."

Zeskind knows that "you probably can't stop one shithead with a rifle," but he believes that Americans can stop white nationalism from becoming a mass movement, even in hard times when it is so easy to blame immigrants, Jews or other scapegoats for economic distress. Aside from prosecuting those who are stockpiling weapons and plotting violence, the best armor against racist extremism is "education, organizing and a good analysis, understanding the exact nature of their ideology."

The greatest future peril may well arise not from the violent fringe but from racialist organizations and ideologues that have avoided violence. "The Council of Conservative Citizens, the successor to the old White Citizens Councils in the South, is the most dangerous even though they're not violent," he says. "A lot of the smart skinhead types are not violent. They're doing subcultural organizing around music and style on the Internet. They are looking for a political vehicle." Many of the most active racialist militants are seeking to infiltrate and influence the "Tea Party" movement that is planning events for July 4 as well as the remnants of the Ron Paul presidential campaign.

How to isolate and disarm these racist elements is a question that confronts responsible conservatives as well as moderates and progressives. Instead of pretending that von Brunn is a "leftist" or dog-whistling to the far right, as figures like Pat Buchanan and Ann Coulter habitually do, Republicans, Democrats and independents ought to find common ground, as the president would say -- and condemn racialism and violence, without exception or excuse.

Shares