(updated below)

In the now famous "white firefighter" affirmative action case -- Ricci v. DeStefano -- the Supreme Court today, in a 5-4 ruling (.pdf), reversed the decision of a unanimous Second Circuit Court of Appeals panel (which included Judge Sonia Sotomayor) and held that the firefighters were the victims of unlawful racial discrimination. The Court split along standard ideological lines (Roberts, Thomas, Scalia, Alito and Kennedy in the majority), with Kennedy writing the Court's opinion. Four Justices agreed with the Second Circuit's panel, including David Souter, the Justice whom Sotomayor has been nominated to replace. Several points are noteworthy about this decision:

(1) In light of today's ruling, it's a bit difficult -- actually, impossible -- for a rational person to argue that Sotomayor's Ricci decision places her outside the judicial mainstream when: (a) she was affirming the decision of the federal district court judge; (b) she was joined in her decision by the two other Second Circuit judges who, along with her, comprised a unanimous panel; (c) a majority of Second Circuit judges refused to reverse that panel's ruling; and now: (d) four out of the nine Supreme Court Justices -- including the ones she is to replace -- agree with her.

Put another way, 11 out of the 21 federal judges to rule on Ricci ruled as Sotomayor did. It's perfectly reasonable to argue that she ruled erroneously, but it's definitively unreasonable to claim that her Ricci ruling places her on some sort of judicial fringe.

(2) The irony of using Ricci against Sotomayor has always been that the reason this case resonates for so many people is due to empathy for the white firefighters. That irony is underscored by today's ruling, as Justice Kennedy devotes multiple paragraphs at the beginning of his opinion to highlighting all of the facts (as opposed to legal arguments) which make people sympathetic to Ricci. Conversely, Justice Ginsburg, writing for the dissenters, noted upfront that the white firefighters "understandably attract this Court's sympathy," but it must be the law -- i.e., long-standing legal precedent and the purpose of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act -- which determines the outcome.

From the start, those protesting Sotomayor's decision in Ricci did so by appealing not to law, but to emotion, non-legal precepts of "fairness" and empathy -- at the very same time that those very same people mocked the notion that those considerations should play any role in judicial decision-making.

(3) For all the chatter about "judicial activism" and that dreadful Roberts metaphor of "a neutral umpire calling balls and strikes," it is so striking how frequently conservative judges invalidate policies which conservatives dislike as a political matter. Here we have the conservative wing of the Court declaring illegal the employment decisions of local government officials, who used a political approach -- diversity -- which conservatives dislike on policy grounds. So often, the outcomes of the allegedly neutral conservative judges are completely consistent with (and aggressively advance) the political preferences of conservatives (Bush v. Gore being only the most obvious example). Indeed, few things are rarer than conservatives Justices invalidating policies that conservatives like politically, or upholding policies they despise -- the true test for whether one applies the law independently of political and outcome preferences.

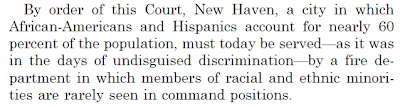

(4) As is true for most discussions of affirmative action, the fight over Ricci has completely ignored the countless ways that whites in America have long benefited, and continue to benefit, from exactly the sort of non-merit considerations which affirmative action opponents decry. As Justice Ginsberg noted, whites had a virtual monopoly for decades on firefighter positions until Congress extended Title VII to public employment ("firefighting is a profession in which the legacy of racial discrimination casts an especially long shadow"), and city officials in this case determined that the test in question was flawed because, among other things, it did not reward merit. The result of the Court's decision in Ricci -- barring the City of New Haven from invalidating metrics with a racially disparate impact -- is this:

Regardless of one's views on affirmative action, the complaints about not-merit-based factors cut both ways. As for Sotomayor, the Court's 5-4 decision today ought to put an end to the attempt to use Ricci to depict her as being somehow out of the judicial mainstream and thus unfit for the Court.

UPDATE: Scotusblog's Tom Goldstein makes several similar points about the decision:

I am struck by the extent to which the majority opinion largely treats the court of appeals’ ruling as a non-event. To the contrary, Justice Kennedy almost seemingly goes out of his way not to criticize the decision below, notwithstanding that the [five-member majority of the] Supreme Court takes a dramatically different view of the legal question. The Court indicates that the state of the law before today’s ruling was “a difficult inquiry,” and that its “holding today clarifies how Title VII applies.” It rejects the plaintiffs’ outright attack on the Second Circuit’s decision as “overly simplistic and too restrictive" . . . .

In the end, it seems to me that the Supreme Court’s decision in Ricci is an outright rejection of the lower courts’ analysis of the case, including by Judge Sotomayor. But on the other hand, the Court recognizes that the issue was unsettled. The fact that the Court’s four more liberal members would affirm the Second Circuit shows that Judge Sotomayor’s views were far from outlandish and put her in line with Judge Souter, who she will replace.

That last sentence is the key point and should end any attempts (other than by right-wing polemicists looking to raise money off her nomination) to use Sotomayor's Ricci decision to depict her as out-of-the-mainstream.

Shares