(updated below - Update II)

A task force appointed by President Obama to issue recommendations on how to close Guantanamo announced yesterday it will miss its deadline and instead needs a six-month extension, potentially jeopardizing Obama's promise to close Guantanamo within a year. The announcement was made in a briefing given by four leading Obama officials, where the condition of the briefing was that none of the officials could be named (why not?) and all media outlets agreed to this condition (why?).

Though the Task Force's final recommendations were delayed, it did release an interim report (.pdf) which -- true to Obama's prior pledges -- envisions an optional, three-tiered "system of justice" for imprisoning accused Terrorists, to be determined by the Obama administration in each case: (1) real trials in real courts for some; (2) military commissions for others; and (3) indefinite detention with no charges for the rest. This memo is the first step towards institutionalizing both a new scheme of preventive detention and Obama's version of military commissions.

From this interim report, it's more apparent than ever that the central excuse made by Obama defenders to justify preventive detention and military commissions -- there are dangerous Terrorists who cannot be released but also cannot be tried because Bush obtained the evidence against them via torture -- is an absolute myth. That's clear for multiple reasons:

First, the Task Force is formulating detention policy not only for detainees already at Guantanamo, but also for future, not-yet-abducted detainees as well. From the first paragraph of the memo (click image to enlarge):

The memo goes on to state that they are examining "what the rules and boundaries should be for any future detentions under the law of war." The anonymous Obama officials emphasized in the briefing that "the goal . . . is to build a 'durable and effective' framework for dealing with the detainees at Guantánamo and future detainees captured in the fight against terrorists."

Nobody is talking about confining the power of preventive detention or military commissions to current Guantanamo detainees who were tortured. The opposite is true: this is to be a permanent, institutionalized detention scheme with the power vested in the President going forward to imprison people with no charges. Claiming this is necessary because of what Bush did to the 230 remaining Guantanamo detainees is a total nonsequitur. If, as Obama defenders claim, that is really the justification, why will these powers apply well beyond that? And relatedly, as I've asked dozens of times with no answer: how can Obama's military commissions be a solution to the problem of torture-obtained evidence when, according to Obama, those commissions -- exactly like federal courts -- also allegedly won't allow evidence obtained by torture?

Second, as a result of breathtakingly broad criminal laws in the U.S. defining "material support for terrorism," there are few things easier than obtaining a criminal conviction in federal court against people accused of being Terrorists. Even if the only thing someone has done is joined a group decreed to be a Terrorist organization, without even engaging in (or even planning) any violent acts, federal prosecutors are well-armed to convict them. In May, the DOJ obtained a conviction in a federal court of a Somalian-Canadian on "material support" charges for doing little more than expressing loyalty to Al Qaeda. Two other Americans of Somalian descent were just indicted on the same charge as a result of their alleged membership in a "militant Islamic group," Shabaab. The FBI website even boasts:

Since the 1990s, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) has investigated and successfully prosecuted a wide range of international and domestic terrorism cases—including the bombings of the World Trade Center and U.S. Embassies in East Africa in the 1990s. More recent cases include those against individuals who provided material support to al Qaeda and other terrorist groups, as well as against international arms trafficker Monzer al Kassar and the Somalian pirate charged in the hijacking of the Maersk Alabama.

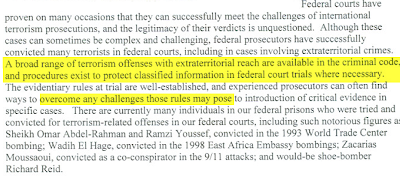

To convict accused Terrorists in court, they need not engage in any violent acts; any involvement with Al Qaeda or other Terrorist groups will suffice. The Task Force's interim report released yesterday itself recognized that the Federal Government is already equipped with extremely broad powers to obtain convictions of Terrorists in federal court:

If we can't even prove in a real court that someone has such minimal involvement with a Terrorist group, then should we be imprisoning them indefinitely? And if the only evidence we have against them was obtained by torture -- evidence which, one should recall, Democrats and progressives insist is unreliable -- then should we really seek to imprison them indefinitely based on such evidence?

Manifestly, this isn't about anything other than institutionalizing what has clearly emerged as the central premise of the Obama Justice System: picking and choosing what level of due process each individual accused Terrorist is accorded, to be determined exclusively by what process ensures that the state will always win. If they know they'll convict you in a real court proceeding, they'll give you one; if they think they might lose there, they'll put you in a military commission; if they're still not sure they will win, they'll just indefinitely imprison you without any charges [a document accompanying the interim report (.pdf) states: "if the prosecution team concludes that prosecution is not feasible in any forum, it may recommend that the case be returned to the Executive Order 13492 Review for other appropriate disposition"]. It's Kafkaesque show trials in their most perverse form: the outcome is pre-determined (guilty and imprisoned) and only the process changes. That's especially true since, even where a miscalculation causes someone to be tried but then acquitted, the power to detain them could still be asserted.

Just look at this intrinsically absurd declaration from the Memo:

For "enemy terrorists" who "have violated our criminal laws," the Obama administration will give people trials "where feasible" -- meaning where it's definite that the Government will win. If everyone the President wants to imprison is going to end up in a cage no matter what -- remember: we're not going to release anyone the President decrees dangerous under any circumstances -- then, other than creating a mirage of due process, what's the point of giving some of them trials? By definition, it's just all for show. I quoted this once before, but it's so apropos; this approach is exactly what is hauntingly described as the Queen's justice in Chapter 12 of Alice in Wonderland:

"Let the jury consider their verdict," the King said, for about the twentieth time that day.

"No, no!” said the Queen. "Sentence first -- verdict afterward."

"Stuff and nonsense!" said Alice loudly. "The idea of having the sentence first!"

"Hold your tongue!" said the Queen, turning purple.

"I won’t!" said Alice.

"Off with her head!" the Queen shouted at the top of her voice.

The Queen's pronouncement -- "Sentence first -- verdict afterward" -- is a fine expression of Obama's approach here: these prisoners are decreed to be Dangerous and Guilty and are sentenced to prolonged, indefinite imprisonment and must not be released; now let's tailor a process for each of them to ensure that this verdict is produced. It's far better to dispense with the ludicrous facade, simply imprison everyone the President wants with no charges, and let the world and the citizenry see what we're really doing.

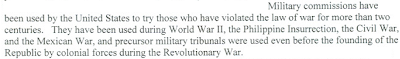

Third, equally false is the Task Force's claim that Obama's military commissions are nothing more than a continuation of longstanding military tradition and, worse, that Obama's commissions resolve the objections long raised by Democrats to Bush's military commissions. Here's what the Task Force asserts in order to make it seem like Obama's military commissions are perfectly normal and consistent with past Democratic objections:

These claims are demonstrably false. While it's true that the Bush/Cheney military commissions were initiated with no Congressional authorization, the commissions were eventually authorized by Congress when it passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006 -- with the opposition of most Democrats, including then-Sen. Obama. As I documented at length here, Democratic objections to Bush's military commissions -- including from key Obama officials -- were not dependent upon any specific procedures, but were opposed to the entire idea of military commissions themselves. If anyone has any doubts about that, just go read the excerpts I posted there from progressives, Democrats and leading newspapers objecting to military commissions themselves, not to the specific Bush/Cheney incarnation of them. What happened to all of that?

The principal argument that was made in the Bush era was that military commissions may be appropriate for standard wars between uniformed armies, but not for the abduction of accused Terrorists far away from battlefields, which -- in terms of the potential both for error and abuse -- far more resemble the apprehension of accused criminals. A November, 2001 New York Times Editorial said the "plan to use secret military tribunals to try terrorists is a dangerous idea" because "by ruling that terrorists fall outside the norms of civilian and military justice . . . . Mr. Bush has essentially discarded the rulebook of American justice painstakingly assembled over the course of more than two centuries." The NYT argued: "American civilian courts have proved themselves perfectly capable of handling terrorist cases." During the 2004 campaign, Obama's current Deputy Solicitor General Neal Katyal vowed that "a John Kerry administration would scrap the military commissions now being used at Guantanamo Bay and replace them with a system patterned on military courts-martial" and he concluded:

The danger with these commissions comes not only in their threat to our Constitution, and our standing in the world as a beacon of fairness, but also in their challenge to the perception of military justice. Our nation—whomever the next president may turn out to be—should admit it made a mistake and return to using our powerful and fair system of courts martial—a system that would generate swifter convictions of terrorists. As our nation's great Chief Justice John Marshall put it in 1803, ours is a "government of laws, and not of men."

Obama State Department counsel Harold Hongju Koh wrote in 2003 that creating military commissions and/or using a new tribunal "are wrong because both rest on the same faulty assumption: that our own federal courts cannot give full, fair and swift justice in such a case," and argued: "No country with a well functioning judicial system should hide its justice behind military commissions." Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Pat Leahy condemned all military commissions, arguing: "it sends a terrible message to the world that, when confronted with a serious challenge, we lack confidence in the very institutions we are fighting for- beginning with a justice system that is the envy of the world." And current Obama State Department official Anne-Marie Slaughter said that, in the past, military commissions had "been used to try spies that we find behind enemy lines" where "you can't ship them to national court, so you provide a kind of rough battlefield justice in a commission," but with the "War on Terror": "That's not this situation. It's not remotely like it."

In fact, the entire 2004 campaign the Democrats ran was based on the argument that Terrorism should be treated far more like a law enforcement problem than a "war." John Kerry famously said: "The war on terror is far less of a military operation and far more of an intelligence-gathering law-enforcement operation." After a series of Terrorist plots were disrupted using normal law-enforcement means, even George Will wrote a column declaring that Kerry was right about this. That the extant system of American justice was perfectly adequate to try accused Terrorists -- and that whole new systems of "justice" need not be created in the name of so-called "war powers" -- was long a central plank of Democratic and progressive objections to the Bush/Cheney approach to Terrorism.

What happened to all of that? As of January 20, 2009, it seems to have disappeared in a cloud of obfuscating smoke, replaced by chest-beating "war"-rhetoric used to justify the creation of whole new "systems of justice" and, worse, locking people up with no trial. Like all new powers vested in the President, once this system is institutionalized, it will be virtually impossible ever to abolish it, or even to prevent its continued expansion.

UPDATE: I was on The Young Turks last night and was interviewed by Cenk Uygur regarding the media's role in investigations and towards the government generally and the Chuck Todd interview specifically. It was roughly 15 minutes long; those interested can listen to it here.

UPDATE II: The always-thorough Daphne Eviatar of The Washington Independent notes the numerous reports from Obama officials indicating the President's commitment to a regime of preventive detention, and she documents that the scheme they are contemplating is virtually identical to what Bush Attorney General Michael Mukasey recommended and demanded last year (during a time when preventive detention was an unpopular idea among Democrats).

Shares