For a bit of change, let's talk about a different kind of health care reform -- the kind that affects the health of the planet.

The other evening, I was listening to "All Things Considered" on NPR. Robert Siegel was interviewing Dr. Hal Levison, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., about the king-size comet that slammed into Jupiter a few weeks ago.

The comet's impact -- it punched a hole the size of the Pacific Ocean, and would have annihilated a lesser planet, like Earth -- was discovered by an amateur astronomer in Australia. Siegel asked how such an event escaped the notice of the world's great observatories.

"There are only a few really large telescopes," Levison explained. "They're hard to get time on, and so they're dedicated to particular projects. And the amateurs really are the only ones that have time just to monitor things to see what's happening."

"Part of the Neighborhood Watch looking out the front door," Siegel suggested.

Neighborhood Watch. Dr. Levison liked that analogy and so do I. Combined with the recent passing of space enthusiast Walter Cronkite and the 40th anniversary of the moon landing, it got me thinking about the value of exploring the cosmos at a time of economic destitution on the ground and a national deficit that makes the word "astronomical" seem inadequate.

As a kid, I was in thrall to the space program. Squinting into the night above rural upstate New York, my family and I sometimes could see those early, primitive satellites traverse the dark sky, and my younger brother, a skilled amateur astronomer to this day, would haul out his telescope for us to look at the craters of the moon, or Jupiter, or Saturn's rings.

In the auditorium of my elementary school, a modest, black-and-white television set was placed on the stage so we could watch the space flights of Alan Shepard and John Glenn, and for a class project in the sixth grade, I tracked the mission of astronaut Gordon Cooper, dutifully moving a tiny, construction paper space capsule across a map of the world as Cooper orbited the planet 22 times.

Six years later, in 1969, we sat downstairs in the family room of our home and watched the mission of Apollo 11. I remember Cronkite's exultant, "Oh boy!" as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the lunar surface, and staying up through the night to watch the first moonwalk. (Years later, editing a TV series on the history of television, colleagues and I noted how, in his excitement, Cronkite almost talked over Armstrong's "One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.")

As time went by, America became blasé about space exploration. The budget for moon landings was curtailed after the first few, and flights of the space shuttle became commonplace save for the horrific, fatal explosions of Columbia and Challenger.

We speak now of returning astronauts to the moon and manned missions to Mars, yet efforts to do so seem halfhearted. But there can be no denying the greater understanding of the universe gained from the amazing images obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope, and data from satellites and unmanned interplanetary probes. And beyond the jokes about Tang and Velcro, NASA and the space program have generated advances in a range of technologies.

Which brings us back to that notion of the Neighborhood Watch, for one of the most valuable contributions of our exploration of the skies has been the knowledge gained from being able to examine our own earthly neighborhood from the distance of space.

Invaluable information is obtained from satellites monitoring weather and the damage created by drought, floods, fire, earthquakes and climate change. But that fleet is aging and few new satellites are being launched to replace them.

Just a couple of weeks ago, Jane Lubchenco, the new head of the National Oceanic and Administrative Administration (NOAA), was quoted in the British newspaper the Guardian. "Our primary focus is maintaining the continuity of climate observations," she said, "and those are at great risk right now because we don't have the resources to have satellites at the ready and taking the kinds of information that we need ... We are playing catch-up."

The paper went on to report that, "Even before her warning, scientists were saying that America, the world's scientific superpower, was virtually blinding itself to climate change by cutting funds to the environmental satellite programs run by the Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NASA. A report by the National Academy of Sciences this year warned that the environmental satellite network was at risk of collapse."

This news comes on the heels of a NOAA report that the world's ocean surface temperature for June was the warmest on record, and the release of more than a thousand spy satellite photographs of Arctic sea ice that were withheld from public view by the Bush administration.

On the morning of July 15, the National Research Council issued a report asking the Obama administration to release the pictures; the Department of the Interior declassified them just hours later. A source told the Reuters news service, "That doesn't happen every day ... This is a great example of good government cooperation between the intelligence community and academia."

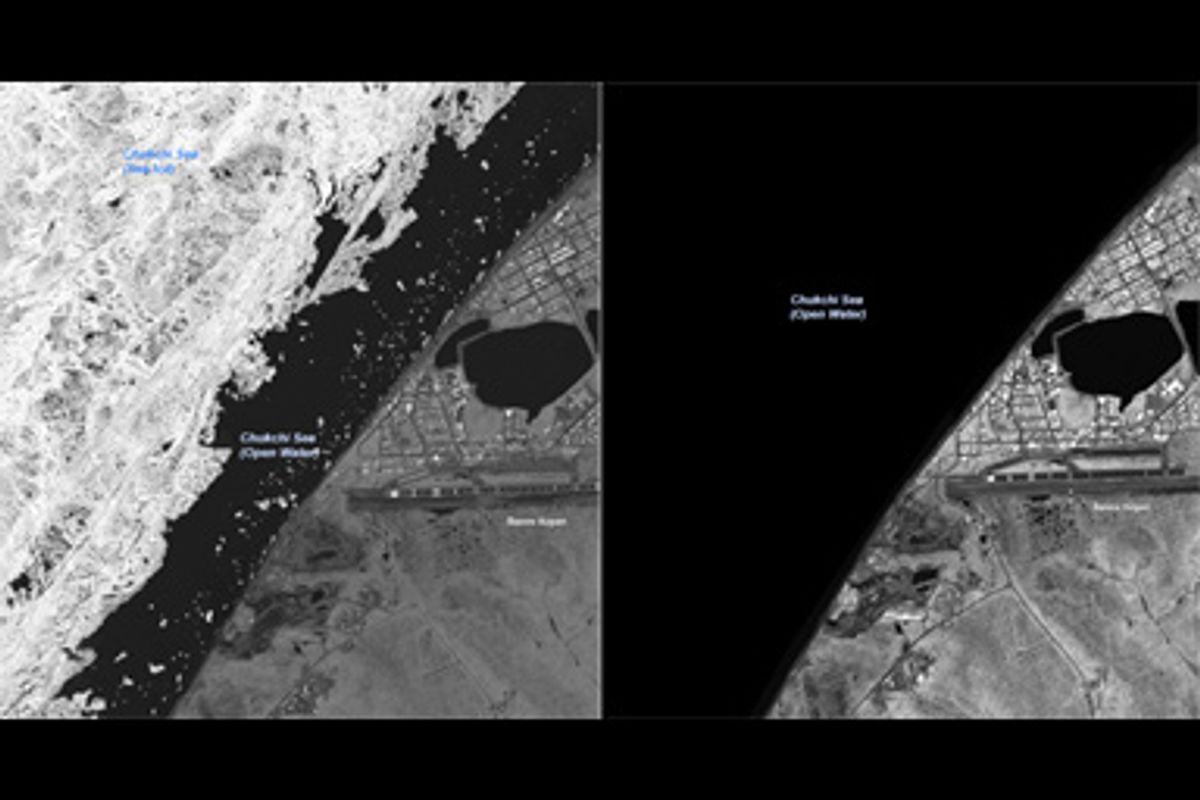

The images are remarkable. You can see a selection of them online at http://gfl.usgs.gov/ArcticSeaIce.shtml. Arctic ice is in retreat from the shores of Barrow, Alaska, along the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska and west of Canada's Northwest Territories, and from the Bering Glacier, among many other sites.

"The photographs demonstrate starkly how global warming is changing the Arctic," the Guardian noted. "More than a million square kilometres of sea ice -- a record loss -- were missing in the summer of 2007 compared with the previous year. Nor has this loss shown any sign of recovery. Ice cover for 2008 was almost as bad as for 2007, and this year levels look equally sparse."

One reason, of course, for the Obama White House's release of the dramatic photographs is to bolster support for the climate change bill narrowly passed by the House and now awaiting action in the Senate.

The bill's a thin-soup version of what many believe needs to be done. It inadequately reduces emissions, gives away permits and offsets to industry, and, as Erich Pica of Friends of the Earth recently told my colleague Bill Moyers on "Bill Moyers' Journal," strips away the Environmental Protection Agency's authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

But even this watered-down version of the climate legislation is in jeopardy, collateral damage from the healthcare reform fight. "A handful of key senators on climate change are almost guaranteed to be tied up well into the fall on health care," the Web site Politico.com reports. "Democrats from the Midwest and the South are resistant to a cap-and-trade proposal. And few if any Republicans are jumping in to help push a global warming and energy initiative."

If true, it's hard to imagine a bill passing before December's U.N. climate change conference in Copenhagen. Harder still, without a law of our own, to imagine the United States being able to convince China, India and developing nations to pass climate regulations and change polluting behaviors.

In other words, there goes the neighborhood.

Shares