It's been a rather big year for Charles Darwin. 2009 is the bicentennial of the man's birth and the 150th anniversary of the publication of "The Origin of Species," and the explorer and naturalist has been the subject of books (including a graphic novel adaptation of "The Origin of Species"), a movie starring Jennifer Connelly (with its own ensuing controversy), and even a viral video hit starring "Growing Pains" actor Kirk Cameron. Given that evolutionary biology is Richard Dawkins' area of expertise, it's unsurprising that the British scientist, atheist and controversial author of "The God Delusion" has also gotten on the bandwagon -- in rather ambitious fashion.

In "The Greatest Show on Earth," Dawkins has written what is essentially a layperson's primer for the theory of evolution. Dawkins aims to explain to the everyday reader why evolution isn't a "theory" but a fact and that we need only look around us to find evidence of its existence -- from continental drift to the reproductive habits of wasps. Dawkins uses simple language, elaborate metaphors and color photographs to make his point, and the result is a convincing, if occasionally dry, overview of evolutionary biology. It's also clear, from the book's first pages, that Dawkins isn't very tolerant of his creationist opponents (the book includes a memorably confrontational encounter with Wendy Wright, the creationist president of Concerned Women for America).

Salon spoke with Dawkins via Skype about creationism's popularity in America, its connection with religion, and how he feels about his own notoriety. A video excerpt of the conversation is posted below.

As you point out in the book, over 40 percent of Americans believe in creationism, which is a higher number than in many other Western countries. Why do you think that creationism has such a strong foothold in the United States?

First of all we have to believe the Gallup polls, and I suppose we do. I mean we believe Gallup polls about other things. You're asking me a question about sociology and comparative religion in different countries. I'm not an expert in that, it's not really up to me to say why the United States and Turkey should be way out ahead or behind in this particular case. It does seem to be the case that of all advanced Western nations the United States is more religious than any other.

Do you also think there's a greater degree of anti-intellectualism in America compared to a lot of other countries?

There does seem to be evidence of a divide in the United States between two cultures. It does seem to be a deeper divide, and maybe even a widening one, perhaps we don't see in European countries. There seems to be a divide between what shall we say -- the Sarah Palin voters and the Barack Obama voters -- who seem to be more bitterly split than the corresponding divides in other countries.

You say in the beginning of the book that you would like to convince people that creationism is not a feasible or a viable belief system, but you also make it clear that you're not a big fan of creationists.

That's putting it mildly, yes.

Doesn't that make it difficult for a creationist to read this book without feeling insulted? Won't that hurt your goal?

No, I'm not really aiming it at creationists. I don't think they read books anyway, except for one book. It's aimed at the intelligent layperson who does read books and who vaguely knows a little bit about evolution and who vaguely knows that there are creationists and maybe even vaguely thinks that he's a creationist himself, but who is curious and wants to know the evidence.

It's just that the evidence is so enthralling, it's so exciting. It is so wonderful that here we are on this planet and we understand why we're here. And it's just a sort of ecstatic feeling to understand why you exist, and I want to share that feeling with other people.

Well, one of the things that you do very well in the book is take this very complicated scientific jargon and scientific reasoning and use metaphors to explain it in a way that a lot of people can understand. Do you think there's a lack of that kind of writing -- explaining science for a broader audience?

There's not exactly a shortage. My book is not the only one that does that. I've always done this. I mean, way back to my first book in 1976, I've used that technique and I've always worked hard to try to make it easy to understand, to try to put myself in the position of the reader, which is a pretty obvious thing to do, really.

Do you think there's a shortage of that being done in education?

I think it would be a good idea if other scientists did more of it, and I think there are plenty of scientists who could do it very well. Really I think it amounts to a kind of responsibility almost, to go out there and explain what it is that they do in entertaining and interesting ways.

The biggest science news of the fall has been the unveiling of this new fossil of a human ancestor named Ardi. How meaningful do you think this discovery is, and how far do you think it's going to go in changing people's minds about evolution?

It's not a new fossil. It's been around for a while, but I understand what's happened is that it's been finally described and published. It's not the missing link. There were many possible links, and this is one of them. It's older than the Australopithecines that we know already, so it seems to fall in the gap that had been left between the Australopithecines and the common ancestor with chimpanzee that we know from molecular evidence lived about 6 million years ago. So Ardipithecus lived around 4 million years ago and the Australopithecines lived about 3 million to 2 million years ago. So this does plug a very nice gap.

Do you think that there's any one particular piece of evidence that will change people's minds about creationism, or do you think that it's really just a question of a gradual erosion of people's belief systems?

I wouldn't expect their minds to be changed by fossils, really. I think the more convincing evidence is the evidence from comparison of modern animals and plants, because we have so many different species, and by comparing them with each other, particularly comparing the molecular genetics which is nowadays very easily done. All living creatures have the same genetic code, so you have an exact digital count of the similarities between every species and every other species, and if you look at that pattern of similarities it falls perfectly into a hierarchical tree. It's a family tree. And even better than that, everything you look at -- every different gene you look at -- gives you the same family tree. That's remarkably persuasive evidence to anybody who attends to it long enough to understand.

You also describe an encounter with Wendy Wright, from Concerned Women of America, in the book. She repeatedly refuses to listen to your arguments and not only that but your evidence. Do you think the debate about creationism is just a question of people not being willing to look at very obvious evidence?

I think that's very clear in the case of the interview with Wendy Wright that she had a kind of willful refusal to listen. She absolutely knew what she believed. She's believed it since childhood. She believes it, because it's in the holy book. Nothing that you could say to her would ever change her mind. That kind of mind is not open to evidence. It is a complete waste of time arguing with people like her. Fortunately there are plenty of other people with whom it's not a waste of time arguing, who simply don't know very much about it, and why should they? There are lots of things we don't know much about, and so I have great hopes -- not of convincing people like her, who are forever close-minded -- but of convincing people who just haven't given it very much thought.

Do you think that it's possible for people to be both religious and believe in evolution?

It's an empirical matter that there are plenty of individuals who can manage to reconcile the two. On that level it clearly is possible, because people like Francis Collins do it. I find it hard to see quite how they do it, but that's the topic of my earlier book, "The God Delusion," rather than this book.

What spurred you to write the book now? Was there any kind of current event or any kind of encounter with a person that made you think that now is the time to write a book about creationism?

It is a book that I ought to have written long ago in a sense because all my books previously have assumed the truth of evolution, and this one gives the evidence. I think that if you actually know why now, it was probably that publishers are so centenary-minded. It is the bicentennial of Darwin's birth, and the sesquicentennial -- if that's the right word -- of the publication of "The Origin of Species," and so those two things came together, and it occurred not just to my publishers but to other publishers as well. But really, the more honest answer is that there was no particular reason. It was just a very exciting subject and what could be better than to lay out the evidence for the dominant and certainly correct view of why we exist at all? What could be more enthralling than that? Why do you need an excuse to write about it?

I certainly remember a lot of what's in the book from my high school and college biology classes. What do you think makes your book more convincing than other past books given the fact that a lot of this information has been around for quite a while?

I don't want to make any false claims for it. I write the books the way I want to write them, and I hope people enjoy them. There are books out there which are very good, and it's up to the readers to read as many of them as they like and decide which version they like best.

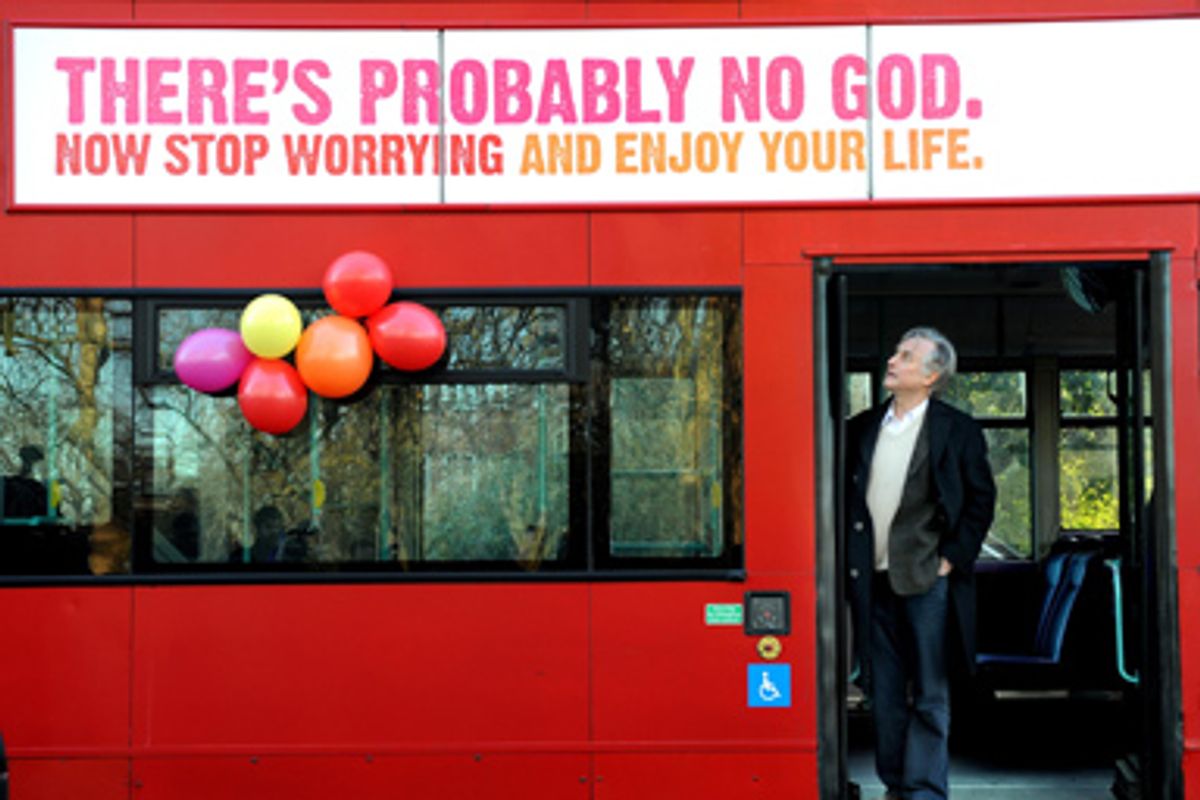

In the past few years, especially with "The God Delusion," you've become sort of an evangelist for the atheist movement. How have you dealt with becoming a more polarizing figure over the past few years?

I don't quite know why it should be polarizing. I like to think "The God Delusion" is a humorous book. I think actually it's full of laughs. And people who describe it as a polarizing book or as an aggressive book, it's just that very often they haven't read it. They've read other people reacting to it. It is true that religious people do react to any kind of criticism as almost a personal insult, it's almost as if you're saying their face is ugly or something, and so that has put out the idea that "The God Delusion" is an aggressive book. You've heard words like strident and shrill, as well. I'd like to suggest that actually it's quite a funny book.

Do you regret having that kind of reputation? Do you feel like it's handicapping you in the future -- that you'll always be seen as having a certain kind of agenda in mind?

Yes, I think it's unfortunate. I think it comes from people who haven't actually read the book, or who haven't actually met me personally, and so I'm described as a very aggressive, strident person, which I'm not.

What's your next writing project?

I do have a plan to write a children's book, which is barely started. It's too early really to talk about that but one of my ambitions has for a while been to write a children's book about science, not about evolution, but about science and about scientific ways of thinking.

Shares