Though Michael Chabon's fixation with DC comics, bisexuality and pink Polo shirts is not exactly "manly," his life -- as evidenced by an endearing new collection of short essays -- has been a picture of modern American manhood. Whereas his last book, "Maps and Legends," mounted a scholarly defense of the genre fiction that formed his literary tastes, "Manhood for Amateurs: The Pleasures and Regrets of a Husband, Father, and Son" charts the landscapes of his childhood and adulthood in a frank, visceral style. To read it is to understand the open line of communication Chabon keeps with his younger self; he seems to recall exactly what it was like to be a kid. Yet, as a father of four and the husband of novelist Ayelet Waldman (a former columnist for Salon), Chabon displays a deep investment in his role as a family man. He has an instinct for good old-fashioned moral righteousness in the face of trouble and temptation.

The funniest of these essays depict the author's metamorphosis from a latent misogynist who takes himself too seriously into a serious man with feminist sympathies. "Cosmodemonic" is a brief portrait of the artist as "a little shit" -- his 22-year-old head full of Henry Miller, recklessly lusting after his female classmates at the University of California at Irvine's MFA program. "The Miller hero -- my hero -- does what he wants, when he wants, whether it makes sense or not," Chabon writes. This pose is crushed after two years of exposure to "the hard-earned skepticism of grown women" in his workshops. Two decades on, in "William and I," we see Chabon protesting the high standards of motherhood compared to the meager demands of being a good dad. And, as if to complete the transformation, "I Feel Good About My Murse" has the 45-year-old Mike proudly shouldering a suede man purse. "I seem every day to give a little less of a fuck what people think or say about me," he confides.

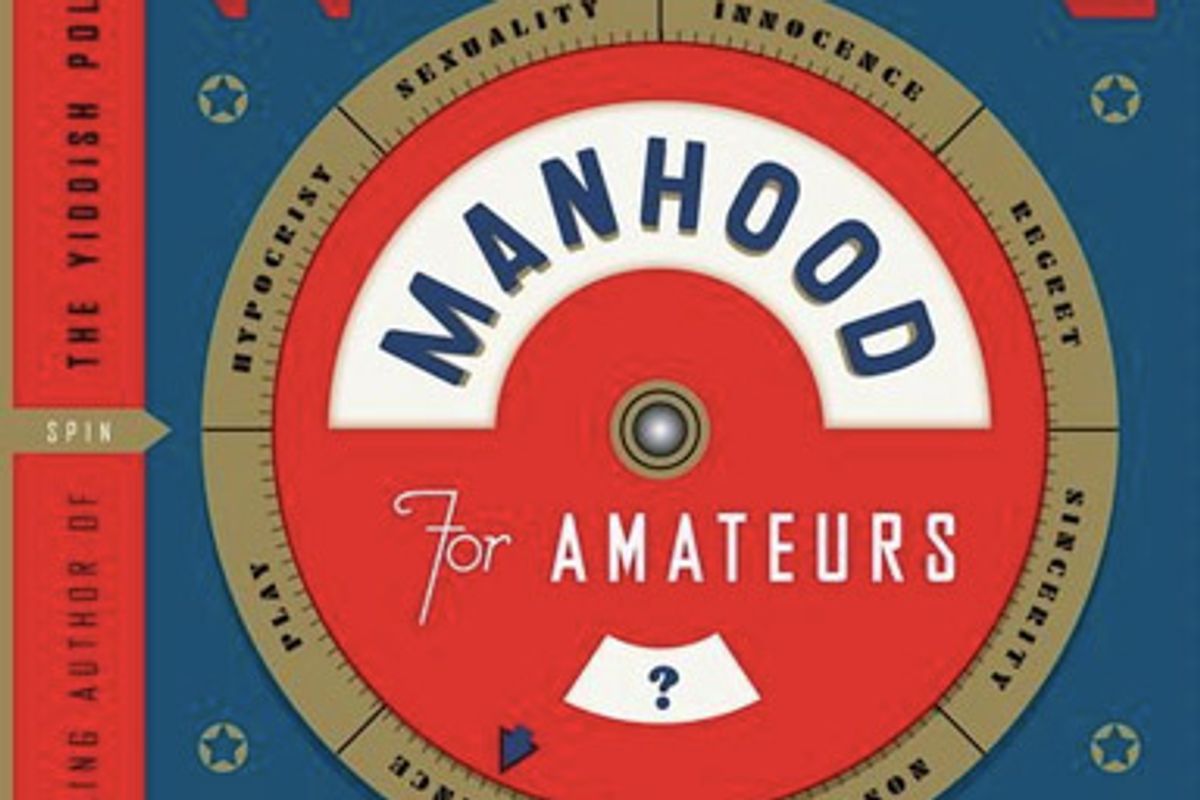

Another of the book's consistent motifs is the disappearance of childhood. With vivid access to his own, Chabon is able to contrast the ways in which his kids' imaginations are imposed upon and pre-imagined by, for example, the "authoritarian nature of the new Lego" and "the orthodoxy of 'Toy Story.'" To Chabon's mind, these products lack the open-endedness of "crap" entertainment like the short-lived "Planet of the Apes" TV show of his youth, into whose shaky plotlines a child could more easily project himself. Still, he trusts in the innovative potential of the child psyche: "Kids write their own manuals in a new language made up of things we give them and the things they derive from the peculiar wiring of their own heads." As a manual to Chabon's own peculiar wiring, "Manhood for Amateurs" makes for an insightful and highly entertaining guide.

Shares