Every year, Christmas is directly responsible for some of the worst books to cross a reviewer's desk: stale, overfrosted sugar cookies loaded with the literary equivalent of artificial coloring and high-fructose corn syrup. But now all is forgiven because the season has inspired Hank Stuever to write "Tinsel: A Search for America's Christmas Present," a portrait of the holiday as it's celebrated in the booming Dallas exurb of Frisco, Texas. A delicately calibrated combination of rigorous reporting, observational humor and old-fashioned empathy, "Tinsel" is the book that saved Christmas for this curmudgeon. The first two sentences alone, with their vivid evocation of big-box America and the promise of more crackerjack prose to come, did the trick:

Before the Black Friday dawn, the sky is still a mix of dark blue and the sick sodium-vapor saffron of the suburban night. I park by the Beijing Chinese Super Buffet and walk across the lot to Best Buy, where hundreds of people -- some in their twelfth or thirteenth hour of standing in line -- await the day-after-Thanksgiving doorbuster sale.

"Tinsel" explores the considerable gap between the Christmases most Americans have and the ecstatic holiday nirvana they long for. One of the three Frisco families that Stuever follows is the Parnells, specifically Tammie Parnell, a 44-year-old mother of two whose titanic drive has been insufficiently tapped by the (supposed) dream job of affluent stay-at-home mom. The overflow of her energy goes into a business she calls Two Elves With a Twist (the second elf quit a couple of years ago, but who needs her?), which puts up interior Christmas decorations for McMansion dwellers who are too exhausted or aesthetically challenged to do it themselves. Rocketing around Frisco in an "enormous, Coke-can-red GMC Yukon XL" she calls "Big Red," Tammie's conversation reels from rhapsodies about how "blessed" she and her clients are to sassy capitalist mottoes: "Moving the merch! That's what I'm all about."

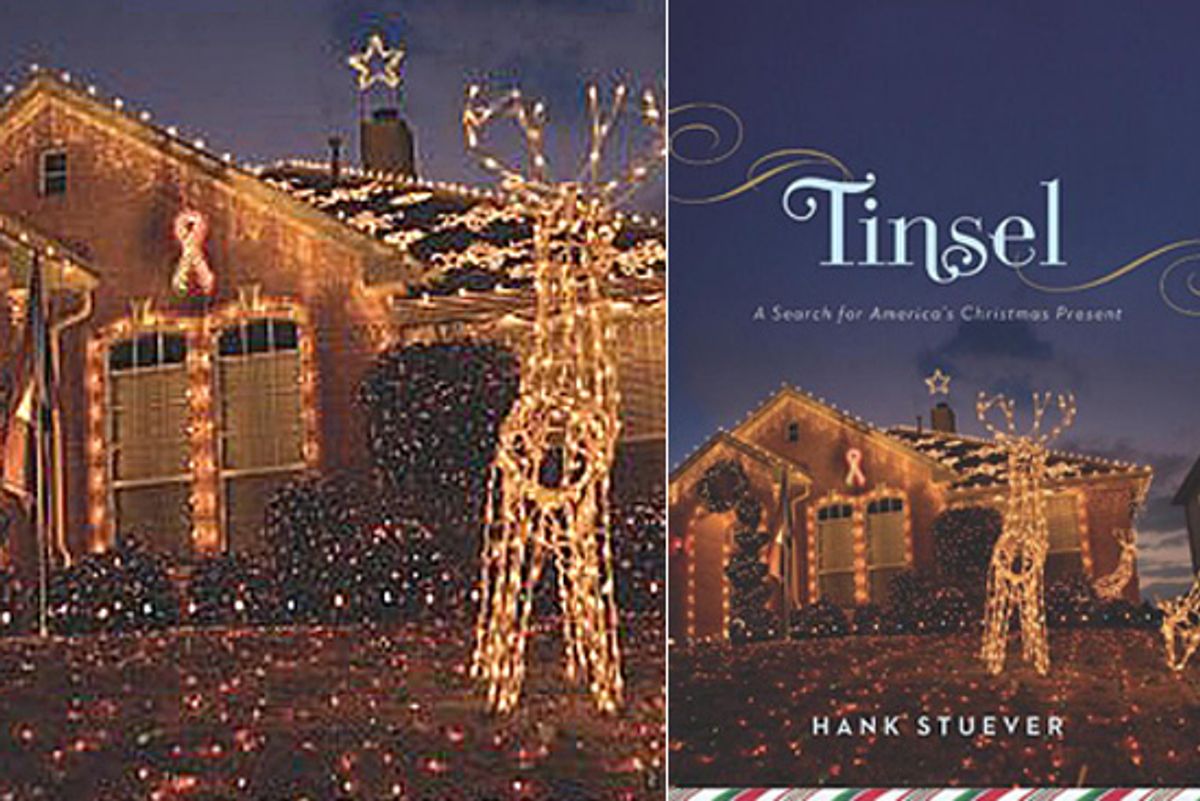

Stuever also got to hang out with the Trykoskis (Jeff and Bridgette), who erect one of those huge synchronized flashing light displays that attract visitors (and traffic) to the neighborhood from miles around. Possibly the most consistently gratified of all Stuever's subjects, Jeff lives to construct this elaborate system, employing 50,000 lights and "$10,000 worth of sixteen-channel control boards" as well as a short-range FM transmitter so that spectators can tune their car radios to the soundtrack. (The song is "Wizards in Winter," by the Trans-Siberian Orchestra, a number Stuever describes as "'Stairway to Heaven' for the men of America who put tens of thousands of Christmas lights on their suburban homes and program them to blink to music.") Hired to design the lights for the faux Main Street of a local New Urbanist development called Frisco Square, Jeff becomes so obsessed that by the end of the book he's buying a shipping container filled with 27,000 sets of LED lights from a factory in China.

Lastly, Stuever spent time with Caroll Cavaso, a single mother of two who has to finance her family's Christmases on a considerably tighter budget; he meets Caroll and her 10-year-old daughter, Marissa, in the line for that Black Friday doorbuster. Tagging along with her, he attends a megachurch, where the pastor "casts himself as a fast-quipping, badass warrior for Christ. He is not above driving a bulldozer on stage to make his point." Frisco is crawling with this breed of preacher; Stuever dubs the typical specimen "Reverend True Religion Jeans" purveying "Venus-and-Mars-style jokes about women and men and relationships, with props. (Don't you hate it when your wife puts the toilet paper on the roll backwards? Don't you just sit there and say, 'Help me Lord'?)"

Despite his own aversion to personality cults and self-help pieties, Stuever clearly likes and respects Caroll, who finds much comfort in her church. The "true openness" with which she welcomes the pastor's nostrums and prefab pep talks moves him. He could be describing his position on Christmas as a whole when he writes, "I believe in little, except, strangely, I do believe in believers."

Though largely immune to the Christmas spirit, Stuever really does like people, and his generosity and curiosity save "Tinsel" from becoming a bitter and all too familiar diatribe against suburban vacuity. He gets consulted by Tammie on whether a mantelpiece display looks better with two or three angels. ("You're really starting to understand your garlands," she tells him. "I need you ... You've got the eye, mister.") He sits in on a tense gift-opening session at the Trykoskis' place. (Jeff's mother objects to his insistence that "we have to be at our house for Christmas, because of the lights.") He marvels as Caroll badly sprains both ankles while working as a stagehand on the megachurch's Christmas pageant and her fellow congregation members respond with self-absorbed indifference.

Stuever may have grown up in a similar Middle American milieu (Oklahoma City), but he's now a pop culture writer for the Washington Post's Style section and, furthermore, gay -- though if he ever told any of his sources this, he doesn't convey their response. Instead, he endeavors to insert himself gamely but unobtrusively into the action, helping Jeff with the extension cords, sniffling over a local radio station's mawkish "Christmas Wish" segments with Tammie and tagging along to the Junior League's 'Neath the Wreath holiday bazaar. (Cutesy names are as common as boob jobs in this town.) He's there when Eitan, a young Israeli working a kiosk at the mall, witnesses the mob assembled for the opening of Santa's Village: "It's insane. I have never seen a Santa Claus. He is like Paris Hilton here."

Stuever spends a lot of time wandering through the Stonebriar Centre mall, and confesses that he enjoys it. Where misanthropes see only a palace of conspicuous and wasteful consumption, Stuever also recognizes that the mall is a place where people gather and wander, sometimes without buying anything. They are "falling in love, or kissing a child ... In this carbed-out consumerismo are places and moments of true bonding, places to be seen and to see others, to simply exist."

This is not to say that Stuever doesn't recognize the demented poignancy of our Christmas complex. One of the book's most fetching moments comes when he ruminates on the avid collecting subculture that's formed around a manufacturer of miniature villages called Department 56, whose products are all Dickensian Victoriana and Bavarian cottages with dollops of painted snow. Department 56 even has a "Christmas in the City" line (featuring the new Yankee Stadium!), but Stuever notes that they have "never issued a Christmas world that actually resembles our own" -- by which he means suburbs like Frisco. "There is no 'box-store village' series in which to place that Starbucks next to the Chili's and the FedEx Kinko's, which could sit on zone 'pads' in front of a porcelain Super Target or 24-hour Wal-Mart ... There is no tiny Tammie flying down a tiny Dallas North Tollway in her tiny Big Red filled with tiny tubs of tiny garlands."

For Stuever, the "village making and controlled reality" coveted by Department 56 buffs is "a constant theme everywhere I go." Frisco -- most of which was built in the past decade -- is a similarly manufactured environment, purportedly everything its residents want in life, yet not the community they choose when it's time to construct the perfect Christmas town out of little china knickknacks. Without belaboring any of his points, Stuever gently unveils a place where, in celebrating their most iconic holiday, people long for a past that never existed, beguile each other with bogus sentimental yarns, scare themselves with the imaginary menaces lurking "outside" their sanctuary and try to retreat further into a safety that actually bores them stiff. That's Christmas, American style: a gingerbread house too small and sweet to move into, but we keep trying all the same.

Shares