Deep within the jargon-encrusted, repetitive prose of Gen. Stanley McChrystal's official assessment of the situation in Afghanistan lies a little-noticed clue to the puzzling plan announced by President Obama this week. In a brief section on "reintegrating" insurgent fighters into Afghan society, the commander of the International Security Assistance Force reviews the most basic reality of counterinsurgent warfare.

"Insurgencies of this nature," he writes, "typically conclude through military operations and political efforts driving some degree of host-nation reconciliation with elements of the insurgency."

The general alluded to this fundamental truth knowing that historically, civil conflicts end with neither a capital overrun by rebels nor an unconditional surrender by them, but with a negotiated solution. In the Afghan conflict, writes McChrystal, "reconciliation may involve ... high-level political settlements" led by the government in Kabul, such as it is. He carefully notes that such negotiations would not be "within the domain of ISAF, but ISAF must be in a position to support appropriate Afghan reconciliation policies," and then goes on to explain why providing jobs and other support to former insurgents must be part of the overall mission.

Perhaps that is why Obama's sober speech omitted the Churchillian flourishes that the right-wing country-club commandos always want to hear. But the prospect of a negotiated solution could explain why the president and his war cabinet have laid out a timeline that proceeds from the onset of the surge to the beginning of withdrawal over a period of less than two years. It may also explain why the rhetoric of both the president and his commanders promises to "stop the momentum" of the insurgency over the coming year or so, rather than vowing the extirpation of the Taliban and its allies.

If a "properly resourced" counterinsurgency force could blunt the Taliban's initiative between now and the summer of 2011, then it is conceivable that some "elements" of the insurgent movement, which is composed of three major and many minor groups, would agree to sit down for talks with the Karzai regime. At the moment -- with everyone agreeing that the insurgents gained the upper hand during the Bush administration's neglect of Afghanistan -- there is little incentive for Mullah Omar or any of the other insurgents to stop fighting and start talking.

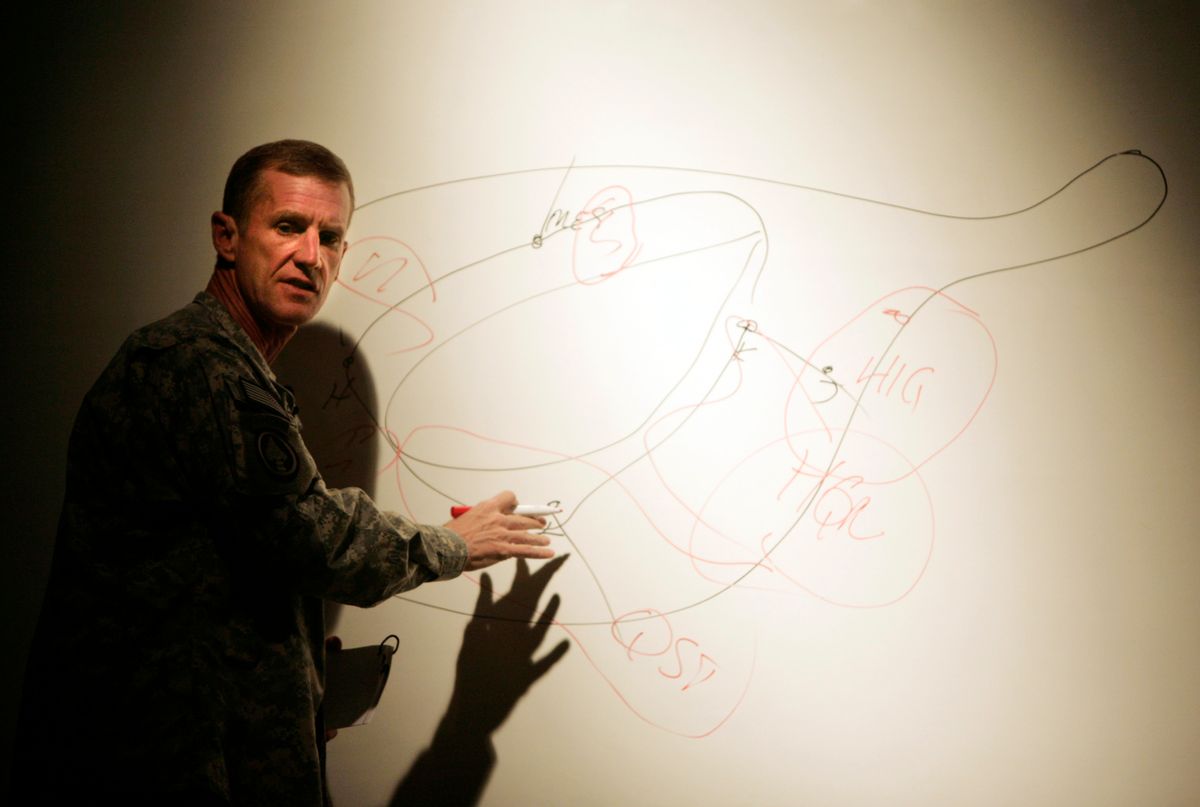

As McChrystal acknowledged last summer, he cannot even accurately estimate how much of the country is controlled by insurgent forces because ISAF has no intelligence about so much of the terrain. Under those conditions, the ambitions of the Taliban remain the same as they were eight years ago -- to regain total control of the "Islamic caliphate" of Afghanistan. So from Obama's perspective, the best and only way to blunt those ambitions is to reverse the course of the conflict, forcing the Taliban and its allies to reconsider their long-term interests.

The argument of the president's critics is that by setting a deadline for troop withdrawals to begin, his plan will allow the insurgents to "lay low" for a year or two. But laying low by definition would require the insurgents to slow down or cease their own momentum -- and let the ISAF and Afghan forces gain ground. The result would be the same: a stalemate on the ground that might encourage negotiations instead of protracted civil war.

Leaving aside for a moment the question of whether American and NATO escalation is self-defeating -- as it may very well be for many reasons -- the urge to drive a bargain might well underlie the Obama strategy. He understands that Afghanistan presents a complex problem and that after eight years of incompetence, arrogance and abuse by the former administration, its troubles are not susceptible to a military solution, if they ever were. Much of the dispute between the insurgents and the government represents long-standing ethnic, tribal and regional grievances, as well as a divide between urban, educated elites and rural, traditional populations.

For negotiations to serve American interests as articulated by Obama, the Taliban and its allies would have to renounce al-Qaida, convincingly and permanently. Some observers have argued that those connections are not as close as they appeared to be in the past -- and the insurgents have tried to portray themselves as nationalist defenders of Afghan sovereignty, not as puppets of a foreign jihadi movement. The latest signal came in their response to Obama's speech, in which they indicated that they will take no terrorist actions against the United States or any other Western governments, merely wishing to drive the invaders off their soil.

From the outset of his campaign, Obama always said he regarded securing Afghanistan as a vital national interest of the United States, and pledged to commit additional troops there if needed. The plan he enunciated and the resources he has committed are unlikely to win a military victory or even achieve stability. What he may hope to do, by preventing a Taliban victory, is to enlist the international community and especially Afghanistan's neighboring states in a diplomatic effort, leading to a cease-fire by the summer of 2011. Then American forces could begin to come home -- and he could plausibly claim to have ended both of the wars he inherited before running for reelection.

Shares