The meeting had been going on for about an hour Wednesday evening when Sen. Chris Dodd, D-Conn., walked out of the room. The lead negotiator on healthcare reform for the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, Dodd should be one of the most plugged-in people in the city on exactly where things stand as lawmakers try to wrap up work on President Obama's top domestic priority. Emphasis on "should be."

"My name is Christopher Dodd," he deadpanned to a crowd of reporters clustered just outside the Senate chamber on the Capitol's second floor. "That's all I can give you, name and serial number."

After more than a year of legislative wrangling on healthcare reform, Senate Democratic leaders suddenly appear to be taking the old cliché about Congress -- that writing laws is like making sausage, and you wouldn't want to see either one up close -- fairly literally, and applying it to their own herd, to boot. Most Democratic senators pleaded ignorance Wednesday to even the most basic questions about where the reform bill is heading. Did a group of five liberals and five moderates reach a deal late Tuesday to pull most of a proposed public health insurance option out of the reform bill, replacing it with an alternative package? What, exactly, would that package look like? And -- most important -- did all the tinkering finally lock up the 60 votes Democrats need to push reform past what's guaranteed to be the mother of all Republican obstruction efforts? The prevailing answer to all of that out of aides and lawmakers alike Wednesday was: Gee, we don't know yet. And we won't know, until the Congressional Budget Office says what the ideas under consideration might cost.

"I think there are very significant issues that have yet to be worked out," said Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, an independent who caucuses with the Democrats. "There are still, from my perspective, some major unanswered questions." Fair enough -- Sanders was not one of the 10 people who have been working on the deal that leaders announced Tuesday night. But Sen. Blanche Lincoln, D-Ark., was one of the negotiators -- and she told reporters Wednesday that nothing was settled: "There was no compromise."

Actually, the outlines of what the group came up with are fairly clear. The public option in the bill now -- as one of a handful of insurance plans uninsured people could choose out of a new exchange to be set up -- would be dropped. Instead, the exchanges would offer a selection of national, nonprofit, but privately run, insurance plans curated by the Office of Personnel Management, the federal agency that handles health benefits for government workers. Uninsured people between the ages of 55 and 64 would also be able to buy into Medicare if they wanted, expanding a program that has never before covered anyone under 65. If private insurers didn't offer premiums cheaply enough to meet some as-yet-unspecified standards, a national public option would be "triggered" into effect. The legislation would also expand Medicaid to cover about 15 million more people than it does now.

But the devil, as they say, is in the details. And no one has them yet. Democrats sent several proposals to congressional budget wonks for a cost estimate; the results of that experiment will determine the specific direction the legislation takes. Conservative Democrats like Nebraska Sen. Ben Nelson and North Dakota Sen. Kent Conrad worry that expanding Medicare could hurt doctors and hospitals, who already complain that the government program doesn't pay them enough for services they render, and bankrupt the government in the process (though that always seems to be Kent Conrad's worry). Progressives fear the private plans won't come close to bringing down costs for people who can't -- or can only barely -- afford insurance now. No one seems to know how much the new Medicare patients, for example, would be asked to pay in annual premiums, or how the government would reimburse providers for their care.

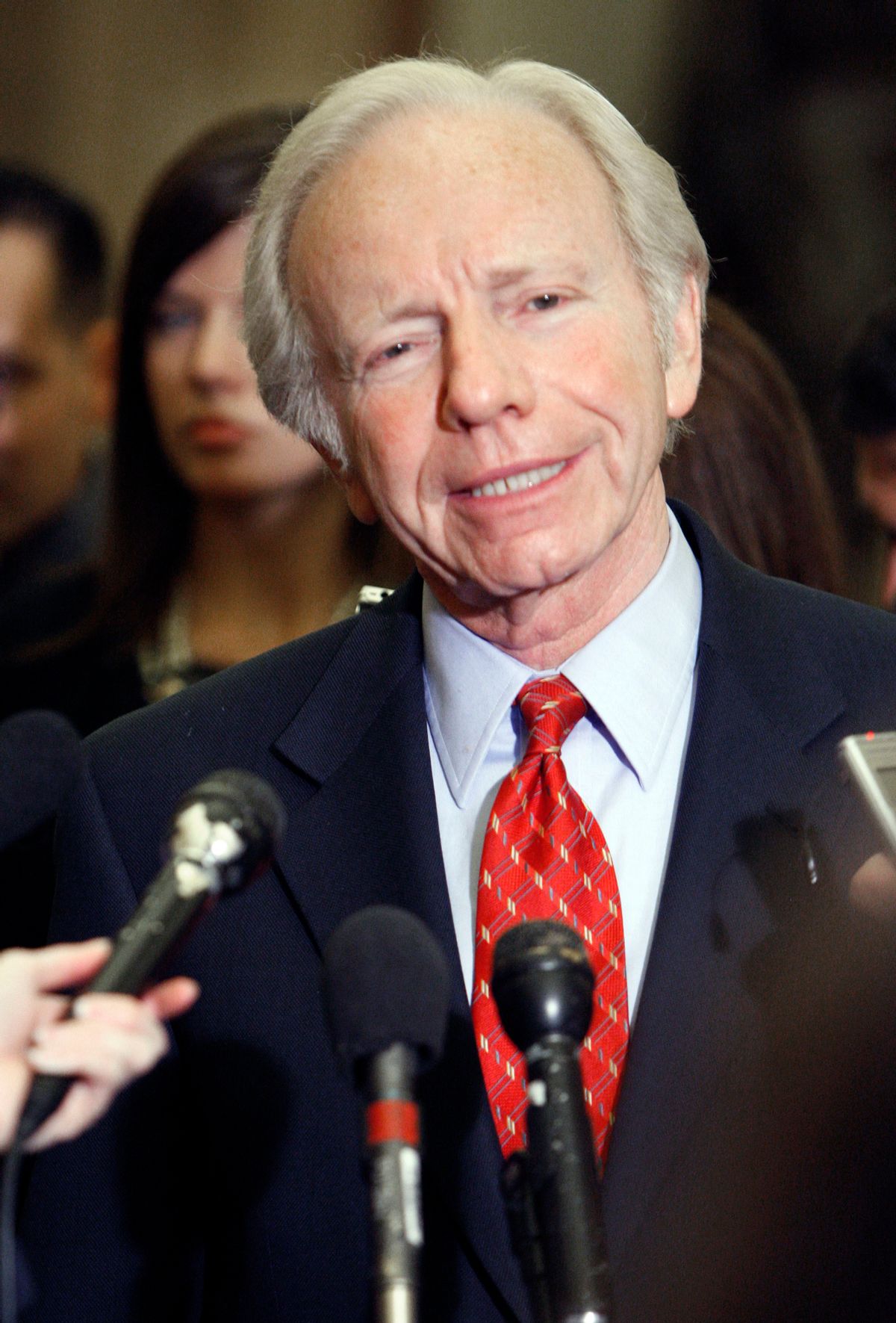

Even once the policy questions get answered, that still leaves political questions. The whole point of the compromise was to pick up a handful of votes that have, so far, eluded Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, especially from Nelson, from Connecticut Sen. Joe Lieberman, or from Maine Republican Olympia Snowe. Nelson said Wednesday that the outlines of the deal sounded better to him than the previous proposal, but wouldn't commit one way or another to it. Snowe -- the only GOP member who's really considered a possible supporter of the reform plan -- seems not to like the Medicare buy-in proposal. And Lieberman, whose 2008 campaign heresies Democrats let slide last year, is doggedly insisting that even a trigger for a public option would be an unacceptable affront to his principles.

Progressives, meanwhile, aren't exactly rushing to sign on with the new plan, either. MoveOn.org e-mailed an urgent action alert to its members, asking them to sign a petition demanding that Democrats save the public option. Influential liberal bloggers came out against it, as well. Labor unions say they'll still insist on a strong public option. House Democrats, who have already approved a bill with a public plan, aren't happy. "At some point in this process, the question became not what was the best policy for the American people, but what could be done to appease a recalcitrant handful who have negotiated in bad faith," said Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., the co-chairman of the House Progressive Caucus.

Even some of the Senate liberals involved in the negotiations sound less than thrilled with it. "The current negotiations are very intense, and compromises are often difficult," said Sen. Jay Rockefeller, D-W.Va., in a written statement just before the evening caucus meeting started. "My final assessment will be of the bill as a whole and my approach on the public option is to stay focused on the goals rather than the title or label of good policy. While I firmly believe a strong public option is the best and right solution -- there are other ways to solve the core problems of affordability and accountability in our broken healthcare system." Vermont's Sanders told me he's worried that expanding Medicaid without doing something to expand access to cheap, but effective, community health clinics could leave 15 million people with insurance they can't use. "That looks good in the newspapers, but it doesn't look good in reality," he said. The Senate bill's plan to tax expensive "Cadillac" insurance plans still doesn't sit well with Sanders, either. "With the cost of healthcare zooming up the way it is, these so-called Cadillacs are going to be junk cars in a few years."

Sanders still thinks the country will eventually have to move to a single-payer healthcare system in order to cover everyone and restrain explosive costs. But figuring out how to work that out isn't something the Senate is anywhere near ready for right now. At the moment, Democratic leaders seem to have more than enough vexing questions facing them to take just these first few steps toward reform. And for now, they would settle for just a handful of answers.

Shares