(Updated with Cheney statement)

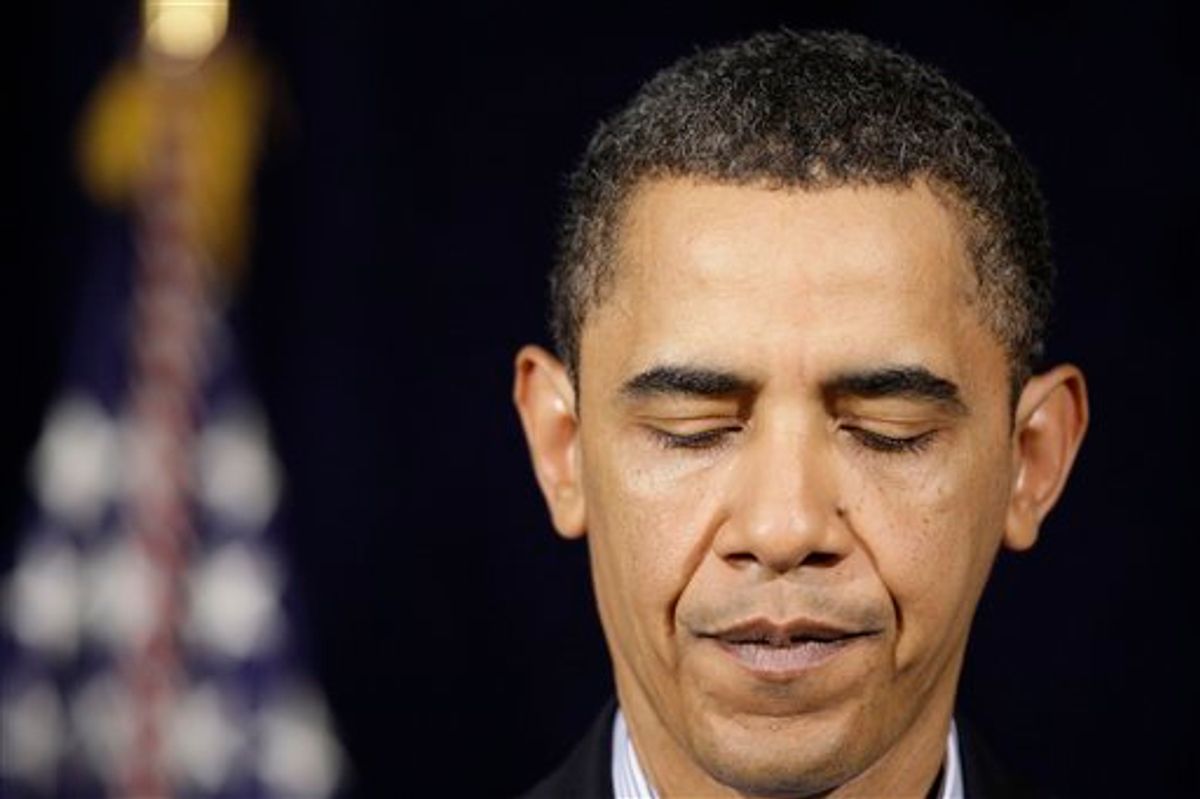

President Obama's candor Tuesday describing the mosaic of warnings about Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab that were mishandled by U.S. intelligence officials shouldn't be noteworthy; it should be routine. But let's be honest, it isn't, and Obama deserves credit for bringing what he called "human and systemic failures" out into the light shortly after he learned about them. It seems intelligence agencies had enough information, some of it admittedly scattered, to keep Abdulmutallab from boarding a plane to the U.S. on Christmas Day. It's hard to think of a comparable example of President Bush being so quickly forthcoming about facts that didn't reflect well on his administration.

So it's hard to know what to make of the difference between media and political reactions to Obama's decision to stay on his Christmas vacation and wait three days to make a comment about the bombing attempt, and President Bush's decision to stay on his Christmas vacation in 2001 — merely three months after the trauma of 9/11 — and wait a surprising six days to even mention Richard Reid's attempted shoe-bombing (and then he only mentioned it in passing.) Even the New York Times raised an eyebrow at Obama's delay in addressing the Christmas bomb plot, describing him as "having emerged from Hawaiian seclusion on Monday to reassure the American public and quell gathering criticism." Republicans like Reps. Pete Hoekstra and Peter King have been nastier (and Hoekstra even had the gall to raise money around the attack).

And hours after this post went up, former Vice President Dick Cheney emerged from his hole and condemned Obama in a statement to his favorite stenographers at Politico: “ [W]e are at war and when President Obama pretends we aren’t, it makes us less safe,” Cheney said. “Why doesn’t he want to admit we’re at war? It doesn’t fit with the view of the world he brought with him to the Oval Office. It doesn’t fit with what seems to be the goal of his presidency — social transformation — the restructuring of American society.” Cheney also seems to be criticizing Obama for trying Abdulmutallab in criminal court — "He seems to think if he gives terrorists the rights of Americans, lets them lawyer up and reads them their Miranda rights, we won’t be at war" — even though the Bush administration did the same with Reid and crowed about his conviction.

Too often Politico seems to see its mission as being an opposition mouthpiece in the age of Obama, but credit where it's due: Josh Gerstein wrote the best analysis of the difference between Obama's treatment and Bush's, "President Obama Takes the Heat President Bush Did Not." Gerstein notes that Bush never made a formal statement about the scare, but merely added a remark in a press conference on other matters. Among the media, only Agence France Presse bothered to remark on Bush's silence, Gerstein found, and Democrats had no comment at all about the president's handling of the threat.

We all understand what makes the right-wing noise machine attack Obama now, but what's the excuse for the New York Times and other media? It's partly that Bush was still wearing his post-9/11 halo, when media and Democrats were loath to criticize him for anything. It may also be our sped-up media cycle, eight years later.

It's probably relevant that Bush was enjoying his highest approval ratings, ever, while Obama's are his lowest, and there seems to be a kind of momentum to negative media coverage when a president hits a rough patch. There may well be fair criticism of the Obama administration when all the facts come out, although whatever happens, it will also be true that the alphabet soup of intelligence agencies the Bush administration assembled to track and find and thwart the bad guys didn't work. Intelligence failures are usually bipartisan problems, given that so many of the players are careerists.

But so far the partisan and media reactions to Obama feel predictably negative, and unfair. Meanwhile, as television, print and Web journalists pore over every fact about Abdulmutallab's confused journey to jihad, there's relatively scant coverage of our escalating attacks on Yemen.

Finally — and this is the sort of thing you're not allowed to say if you are, as Glenn Greenwald notes, a Serious Journalist — but every time I see Abdulmutallab's face I'm struck by how young and vulnerable he looks. His troubled Web writings left the same impression. I'm not sure what that means. He is, increasingly, the face of young militants — the product of a good home and education, even wealth, not of slums and deprivation (although the poverty and chaos of Yemen, Afghanistan and Somalia certainly contribute to al-Qaida's strength and appeal there). Abdulmutallab reminds me more of a troubled American school shooter than, say, Mohammed Atta. Al-Qaida's appeal to such lost souls may well be high, but it's a misery that crosses boundaries of religion and race.

Predictably right-wing gas bags are as hung up on Obama calling Abdulmutallab an "extremist" and not a "terrorist," as they were about the administration (and some of the media's) failure to brand Fort Hood killer Maj. Nidal Hasan with the same label. Appallingly to the right, some coverage of Hassan's horrific assault focused on his mental health problems, and the signs of psychological trouble that his colleagues and superiors either missed or ignored. "Terrorist" provides a label that absolves us from paying attention to things like mental illness — let alone whether our expanding war against Islam might be creating more "terrorists" than it's killing.

That's all too complicated: Let's just focus on why Obama took so long to talk about Abdulmutallab, OK? Then nobody needs to really think about what we're up against in any meaningful way.

Shares