British director Peter Hall once said of another British Peter, one named Sellers, "It's not enough in this business to have talent. You have to have the talent to handle the talent."

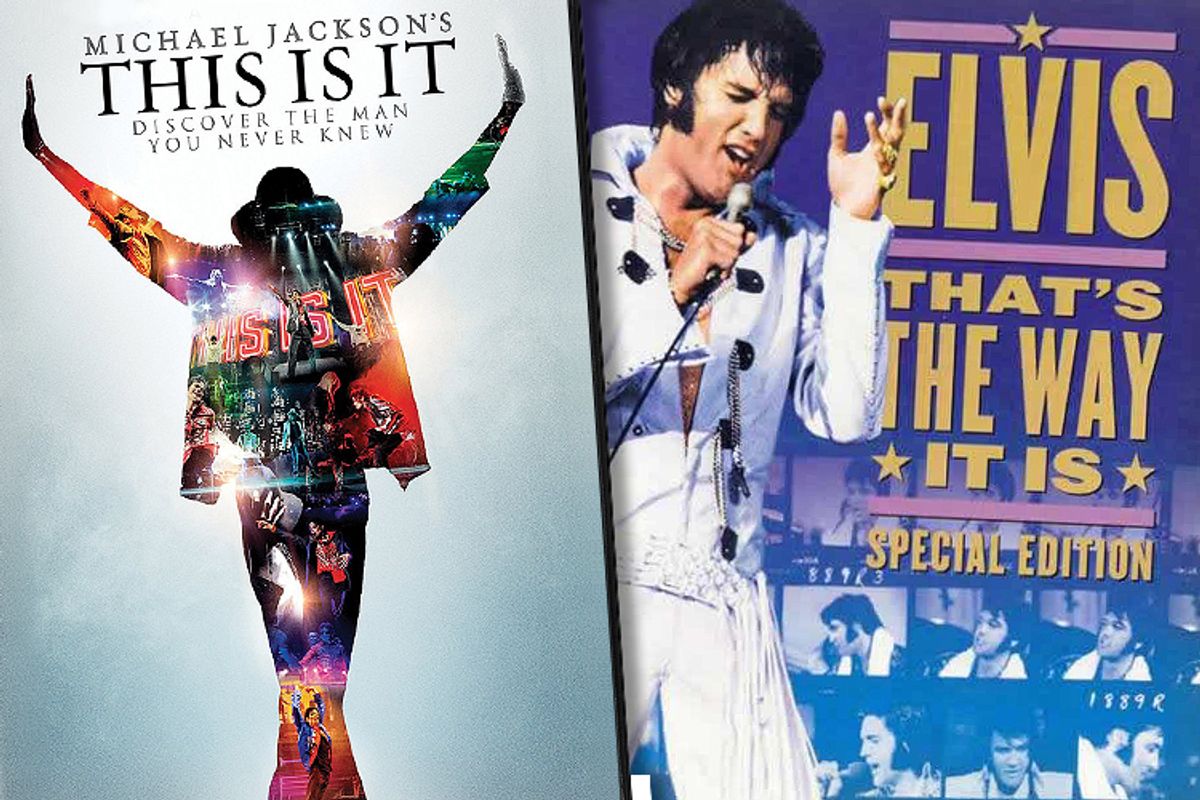

This dark art of handling the talent and dealing with deification is the tie that binds this week's Double Bill, which would be today's release of "This Is It," and its doppelgänger, the 1970 documentary "Elvis: That's the Way It Is." Obviously, it does not take any particular genius to point out connections between Michael Jackson and Elvis Presley. Haunted relationship with parent, incomprehensible musical genius, pet chimps, oh yeah, Lisa Marie, to count off just four of the easiest ones.

But this one-sided Death Match between legend and life is what ultimately tied these men together. Elvis and Jackson brought an impermeable membrane of fame and self-delusion with them that kept the real world outside their experience. Both "This Is It" and "The Way It Is" shoot through that membrane, and those rare glimpses of the tortured soul inside are what give the films their real power.

This "splendid isolation," in the words of Warren Zevon, made the end of their careers a slow-motion bus wreck -- and we were all bozos on that same bus.

"To me," wrote Bruce Springsteen the week Elvis died, "he was as big as the whole country itself, as big as the whole dream. He just embodied the essence of it and he was in mortal combat with the thing."

From about that moment on, Springsteen consciously crafted that growth industry called his career on Elvis' shaky foundation. The lessons he has articulated over and over again in both song and interviews are his attempts to try to live outside that bubble of fame. But it isn't easy. In a recent small book by Big Man Clarence Clemons, the only truly insightful and honestly disillusioning images that emerge are Springsteen's private jets flying from concert to concert, and the alpha celebrity decorum of who sits just where along the way. And, oh yeah, a second jet for the wife and her entourage. And special planes dispatched for the likes of Brian Williams. But, as Clemons (actually, probably, his hack ghostwriter) points out, Springsteen does make a point of personally greeting everybody in all rows, on every flight, so, it's a start.

I guess.

Springsteen's talent has been very comprehensible, and his career arc tightly controlled. Bob Dylan's talent belongs more in the incomprehensible category, and he has somehow made it work for him. For the last 20 years, Dylan has conducted a bold experiment in hiding in plain sight, called the "Never Ending Tour." Night after night, Dylan appears in State Fairgrounds and minor league stadiums in minor league towns, and at night, according to at least one local police report, roams the streets in hooded sweatshirts, searching for Dylan knows what.

Nobody is more closely guarded than Dylan both on- and offstage, in all senses of that word, but somehow, he stays connected to his muse, and it, somehow, to him. If anything, one of his many particular geniuses has been turning the very act of retreating from legend into accelerant for its fire. It's only in the last 20 years where Dylan finally carries the burden he promised he would heft in the notes to his second album. "I don't carry myself yet the way that Big Joe Williams, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly and Lightnin' Hopkins have carried themselves. I hope to be able to someday, but they're older people."

Bob Dylan made that legend thing work for him, and only went a little crazy along the way. But as we all know, Elvis and Jackson went big-time crazy, and if you know where to look, you can see in these two films just where -- and maybe, why.

While Elvis was in mortal combat with some kind of dream of America, Michael Jackson became the poster boy for an even more devolved America, one where self-delusion, narcissism and grotesque materialism are somehow mistaken for canny career management. He even had the spectacular bankruptcy thing going for him, with the promise of an impending bailout, if he could pull off that one last desperate deal.

Which leads us to this week's release of "This Is It" -- a film swept off the cutting-room floor of Jackson's last hurrah, and last rehearsals.

To be clear, this film was originally conceived of as a home movie, financed by Jackson personally. Had things gone differently, an abbreviated version might have appeared as a supplement on some future holo-hagiographic 3-D monolith box set commemorating Jackson's 10th year onstage at the Luxor in Vegas. And like so many DVD supplements, there is a cheap, offhand quality to the production.

But what keeps this "This Is It" from being a shameless exercise in commercial necrophilia is the sheer joy of watching a performer, if not at the top of his game, in the bullpen warming up. Based on the performances here, Jackson had it until the end. Just what "it" was remains open to debate, and this movie does not help the discussion.

Throughout the two hours, Jackson stands alone, surrounded by indifferent technicians, a puppet being put through his paces by the Geppetto of his own ego. Many of the production numbers look as if they were choreographed by Albert Speer, and the fascist architecture of the proceedings don't shed much light on their creator.

It helps that much of Jackson's dialogue is subtitled, for he seems to be speaking a private language. "I'm trying to adjust to the inner ears," whispers Jackson at one point, "with the love -- L.O.V.E. It's not easy, though."

Tell me about it.

Director Kenny Ortega cajoles Jackson like a toddler being coaxed to eat his broccoli. Jackson is clearly phoning it in, but one is often reminded, what a phone.

One such moment occurs at the end of "I Just Can't Stop Loving You," where Jackson takes off at the end of a duet with an anonymous background singer. This sequence is intimate, sexy, and we see Jackson momentarily possessed by the music and his muse. But then, the song ends, and Jackson crashes back to Earth, clearly angry at being led to this kind of self-revelation. You see for an aching moment the raw talent that Jackson had all the way to the end, and then, the door slamming shut on it.

Which brings us to our second feature.

"Elvis: That's the Way It Is (Special Edition)" was shot in the summer of 1970 and reworked by TCM for this 2001 rerelease. It is perhaps the best surreal evocation of the '70s since "Zodiac," except, of course, this is a documentary. Shot by the great Lucian Ballard, it brings you as close to the real Elvis as you want to go.

The film begins with some more tantalizing rehearsals. The musicians look at Elvis like the borderline hysteric family looked at demon child Billy Mumy in that great "Twilight Zone" episode. It feels like everyone always laughs a millisecond too late at his jokes, and you can feel his entourage praying that they too don't get wished into that cornfield. Why is it not at all surprising that Rod Serling's opening narration from this "Twilight Zone" episode was sampled in 2001 for a song called "Threatened" -- by Michael Jackson? In one particularly gruesome sequence, Elvis has an onstage water fight with members of the Memphis Mafia. When Elvis, in a flash of feigned anger, picks up a mike stand, as if to impale them with it, you get the idea that this, in fact, could happen.

It is clear that Elvis just had nowhere to go, no one to talk to about the hellhounds on his trail. Every conversation is a transaction, and Elvis knows it. The striking thing is how little is different backstage from onstage. Same jokey nervousness, same nonchalant diffidence to his musical gifts. Elvis was always on, and could just never get off. In all of the footage, he can't stop moving, looking for distraction from the Sisyphean task of just being himself. One can see his genius emerging like the chest buster from "Alien," and at times, Elvis looks as shocked at the results.

At least Bruce Springsteen can get it off his chest with Brian Williams.

But there are compensating musical treasures. Where Elvis is all looseness and evasiveness, lead guitarist James Burton is all paisley precision, spitting out chicken-licking' licks and anchoring the proceedings like the Country Gentlemen he is. "Play it, James," Elvis regally commands, and Burton does just that, brilliantly. When they swing into an impromptu medley of "Little Sister" sliding into "Get Back," one wishes that the Beatles, instead of breaking up that same summer, had dropped by this rehearsal studio instead.

They might have changed their minds.

When we move to Las Vegas for the pre-show rehearsals, you can feel the dingy surroundings and smell the fossilized cigarette smoke in the carpets of the "International Hotel" where the show had to go on.

Shot across six nights, the performance footage is a Groundhog Day's nightmare of the same songs, same fans, same jokes. Here we stand by helplessly as Elvis, as described in some other lyrics of Zevon, throws it all away for that "porcelain monkey," and his face on Velveteen. There is a viscous quality in the film, like you are trapped in the amber with Elvis, and after about an hour, you just want to get out of there. At one juncture, during "Love Me Tender," as Elvis leaves the stage and walks deep in the ballroom it feels like nothing so much as watching grainy footage of a Bigfoot sighting.

Watching him kiss one bouffant fan after another, on the lips, you truly get a feeling of what hell must be like. At one point, one hysterical, crying fan almost swallows Elvis alive. He pulls back in shock and discomfort, but then, moves to yet another predatory encounter. And another.

Six nights, and then, 600 more nights, until it all ran down.

It is clear from both of these films that Michael Jackson and Elvis Presley were getting everything they wanted, and nothing they truly needed.

As William Carlos Williams so famously wrote, "The purest products of America go crazy."

That was the lecture.

These films would be the lab.

Got any fly-on-the-wall-of-musical-train-wreck "Double Bill" ideas for "This Is It"? That Wilco film, "I Am Trying to Break Your Heart?" "Don't Look Back," or better, a bootleg of Dylan's 1966 surreal masterpiece, "Eat The Document"? Kirk Douglas IS a chin-dimpled Bix Biederbecke in "Young Man With a Horn"? Do tell!

Shares