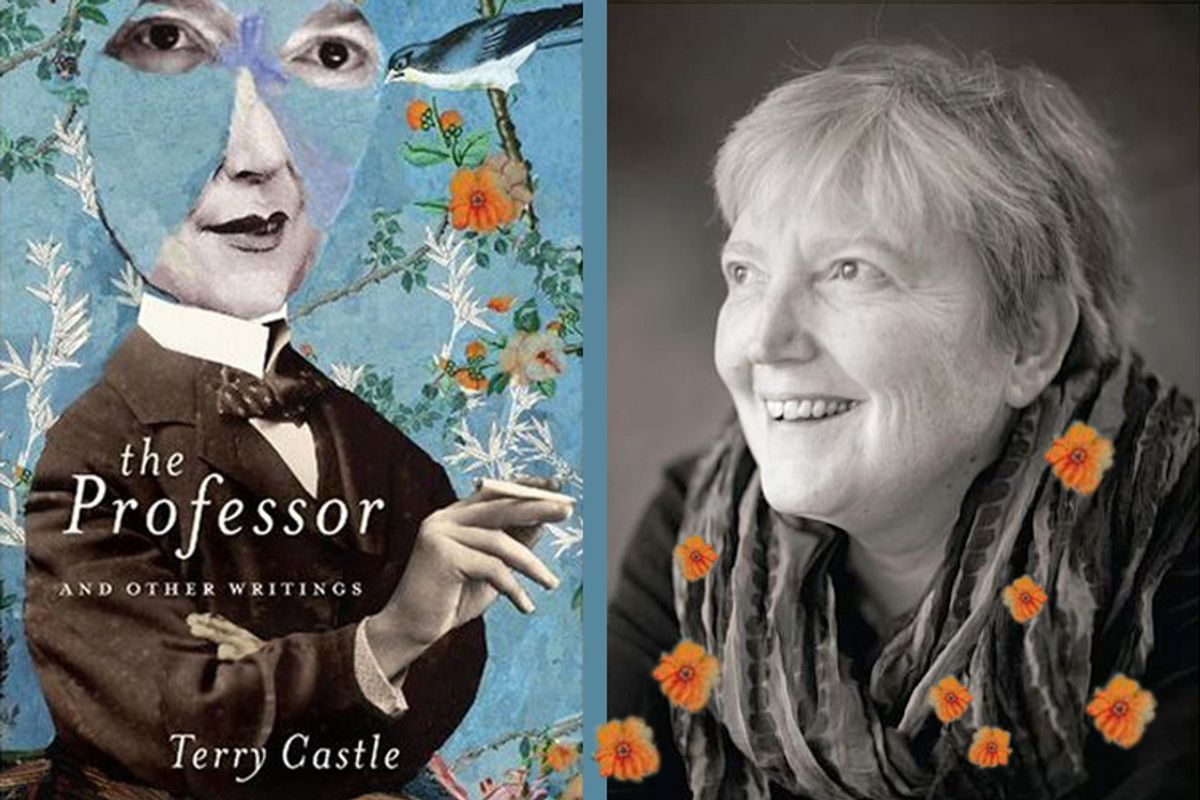

Susan Sontag once called Terry Castle “the most expressive, most enlightening literary critic at large today.” But her new book, "The Professor and Other Writings," proves she's one of our most expressive and enlightening memoirists as well.

Having scrutinized the lives of Sappho, Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein, Castle here investigates her own relationships and obsessions -- including Sontag herself, in a hilarious (and not entirely flattering) meditation on their rocky friendship called "Desperately Seeking Susan."

The rest of the material is rather bleak: pilgrimages to World War I battlefields and the Palermo catacombs, psychotic step-siblings, a traumatic graduate school fling with a crippled female professor. Yet every page hums with a kind of cathartic glee -- a testimony to Castle’s ability to transform even the grimmest scenarios into savage comic prose. One-liners abound ("If one had to be female, after all, one might as well be Janis Joplin," she writes of her attempts to blend in with '70s hippie-chic.) And a serious knowledge of feminist theory mingles with digressions on the "hotitude" of Daniel Craig. "The Professor and Other Writings" documents a brilliant mind discovering a deeper, more intimate mode of expression.

Salon spoke to Castle over the phone in her San Francisco apartment about feminism, Susan Sontag’s sexual ambivalence and Tiger Woods' "unsettling" Vanity Fair cover.

You’re known primarily as a literary critic and scholar. What triggered this shift toward memoir?

Maybe inside every English prof there’s a writer screaming to get out? Certainly there was in me, even when I was writing more conventionally academic books. But lately I’ve also felt increasingly estranged from the sort of jargon-ridden pseudo-writing that for the past 10 or 15 years has been emanating from so many college English departments. Much of what passes for advanced literary scholarship these days is dreadful twaddle -- incoherent, emotionally empty, deeply illiterate. A lot of ideological posturing goes along with it. I’d gotten sick of it -- all the p.c. preening and plumage display -- and wanted to write more frankly and personally, and if I could with a certain lyricism and emotional force.

In your essay on World War I, you confess that you covet male bravery, even though this strikes you as a somewhat non-feminist thing to say. How do you reconcile this admiration for men with your own feminism?

When the piece first appeared it’s true some female readers didn’t like it. The odd banshee squeal could be heard. But I do think men and women are socialized differently and that boys -- generally speaking -- are taught to be physically brave and uncomplaining in a way that most girls still are not. I’ve always suffered from a physical courage-deficit and it bothers me. I wish I were more manly. Less inclined to gibber in fright. I’d even settle for being a noble Roman matron. Death before dishonor, etc. And maybe envying men their sang-froid is a feminist impulse after all -- you want to take what is useful and good from the other sex. Equalize things a bit. Men in turn might learn to be more feminine in certain respects.

Your infatuation with Susan Sontag, whom you became friends with later in life, is similar to your infatuation with the Professor, the charismatic female teacher with whom you had an affair in grad school. Do you think sexual desire is linked to hero worship?

Yes, and vice versa. Intellectual admiration has always gone along -- sometimes confusingly, I admit -- with sexual attraction. When I was young certain teachers could elicit a sort of supercharged mental excitement in me -- a dizzying sense of being hailed by an adult -- which very easily tipped over into infatuation. One of the interesting things about Sontag was that she shared the tendency. In some ways she was rather like an overgrown schoolgirl, prone to goofy intellectual crushes. Enthusing with her about her heroines -- Marie Curie, George Eliot, Marina Tsvetaeva -- was like being a co-conspirator. You were two BFFs gossiping about the unbelievably gorgeous Brainy Teacher-Lady. I think Sontag tried to suppress this juvenile, crushed-out side; it definitely went along with a certain fickleness, even dilettantism, in her nature. She would take something up -- a person, an idea -- with enormous ardor; then all would suddenly be exhausted and she would move on to the next thing.

Writers like Edmund White and Allan Gurganus have criticized Sontag for not coming out publicly as a lesbian. Do you see this as a shortcoming on her part?

It depends on what sort of mood I’m in. When I hear the Nice and the Good abominating same-sex marriage, I wish everybody would come out. Dogs, cats, the little raindrops falling from the sky, the kitchen sink, etc. I guess with Sontag, her discomfort and reticence strike me now as more poignant than anything else. She was permanently ambivalent about female homosexuality, in a way I can understand, even if I don’t feel that way myself as much as I used to.

Dan Savage recently told the New York Times that when you press people on their opposition to gay rights, it often comes down to sex between men. Do you think the gay marriage ban has more to do with a stigma attached to gay men than gay women, considering the existence of shows like "Ellen" and "The L Word"?

Dan Savage may be right. Male homosexuality was a criminal offense in England in Oscar Wilde’s day, for example, and punished very severely, whereas lesbianism was totally ignored. As far as the law went, it was as if lesbianism didn’t exist.

And yes, while straight men may be repulsed by gay male sex, they often find lesbianism titillating: It’s a huge theme in straight-guy porn. Does this add up to some greater public tolerance for lesbians? I don’t know. I’m not sure one can extrapolate one way or the other from television shows: Lesbians and gay men both tend to be treated in them as eunuchs -- sentimental sexless sitcom clowns. Ellen -- and I don’t mean this as a slam, quite the opposite -- is the lesbian Doris Day. Cute, pliable, utterly unthreatening. "The L Word" tried to hot things up a bit, but for whatever reason, I think it passed most straight people by.

Sex, particularly lesbian sex, is a consistent theme in your new book. What did you think of Katie Roiphe's recent essay on the lack of carnality among today’s young American male novelists?

I enjoyed Katie Roiphe’s article immensely. She’s right. Some of these "emo-guy" writers -- I won’t name names -- suffer from advanced cases of male estrogen oversaturation. They have the heartbreak of floppy-man-boob disease. And no, I’ve never been bothered by carnality in writing. I think Philip Roth is a genius. Male horn-dogging doesn’t bother me that much. (Maybe because it doesn’t affect me directly.) The writing is what matters. I once saw Norman Mailer jogging shirtless in Provincetown in some huge, billowing turquoise Lonsdale boxing trunks. A lumbering and majestic sight. I’ve been trying to emulate the look myself ever since.

In the essay "My Heroin Christmas," you write about being attracted to the drug-addicted wild-man jazz musician Art Pepper. How do you account for his ability, or any male artist's ability, to kindle erotic yearning in lesbians?

Pepper’s memoir, "Straight Life," is one of the great American books of all time. Pepper was a heroic, japing, inspired autobiographer, just as he was a sublime alto sax player. And in the 1940s and 1950s, when he was a beautiful young punk, he was also beyond dreamy-looking. I don’t know how anyone of any sexual orientation could have resisted him. He made Chet Baker look babyish and insipid.

I guess what I find, too -- in both Pepper’s playing and his storytelling -- is an emotional daring so intense as to feel arousing, or close to it. He connects -- it’s almost like someone whopping you in the face -- except it’s deeply pleasurable. It gives the lie too to all those moldy post-structuralist arguments about the death of the author. This guy ain’t dead. And he makes you realize you’re not dead either. He’s right in there with you, body and soul.

Your area of expertise is 18th century popular literature. Do you have a similar interest in pop culture of today?

Certain pop phenomena strike me forcibly; others not so much. I adored Susan Boyle and her eyebrows from the start. I found myself absolutely transfixed yesterday, for example, when I got my latest issue of Vanity Fair and saw the Annie Leibowitz photograph of Tiger Woods on the cover. He’d obviously been working out -- he’s all sweaty, bare-chested, and has a little woolly ghetto-hat on. You can even see some of his damp pubic hair! The picture is so hot it’s unsettling. (He also looks weirdly like the underwear bomber.)

Apparently Leibowitz took the picture before the business with the Escalade and all hell broke loose. You have to hand it to her: She has an uncanny knack for taking pictures of people right before something completely unexpected, momentous -- even cataclysmic -- happens to them. Those extraordinary naked photos of John Lennon, for example. I’d be scared if she wanted to take my picture: It’s like the Curse of the Bambino.

What do you do in your spare time?

My interests tend to be eccentric. I’m a devotee, for example, of a British magazine called the Wire (nothing to do with the TV show, by the way, which I have seen). It’s all about weird avant-garde music -- gamelan-grunge orchestras, Norwegian thrash, Library Music, the club sounds of Kuala Lumpur and so on. Really arcane stuff. I also collect a lot of fairly peculiar, non-girly things: old tintypes, mug shots, World War I memorabilia, printers’ blocks. They know me over at eBay. There’s a geeky, scavenging, Cabinet of Curiosities aspect to my intellectual and entertainment life.

You’re fairly active in social media. What’s the allure?

Never in a million years did I think I’d get sucked onto Facebook, but suddenly the whole world is on Facebook. Unlike e-mail, that odious invention, it’s a pleasant, undemanding way of keeping in touch. One unwritten rule is you don’t use it to pester people. I also enjoy the extraordinary historical performances people find on YouTube and put up on their posts. Callas and Tito Gobbi in Paris in 1957, etc. I have a blog for my artwork too -- Fevered Brain Productions. I was thrilled HarperCollins used one of my own images for the cover of the new book. Blogging is like having your own vanity press. What’s not to like?

Shares