I have a friend from graduate school who, at 10 years old in rural Wisconsin, got his hands on "A People's History of the United States." He read it, and when he was done, he wrote Howard Zinn a letter, asking how to contribute to work of the kind Zinn was doing. The historian bothered to write the kid back, and laid out a path for him that led him to where I met him -- graduate school in history.

The story’s touching, I think, because it’s exactly the gentle-hearted and populist kind of thing a Zinn admirer would imagine he’d do. There’s something fitting about how Zinn’s peak of celebrity may have come about thanks to the working-class genius played by Matt Damon (his next-door neighbor in Boston) in "Good Will Hunting." (At one point in the film, Damon's character plugs "A People's History" to his therapist, played by Robin Williams.) At the heart of Zinn’s sensibility was the idea that American history is not the exclusive province of senators and generals or, for that matter, historians. It belongs to everyone (a notion he touched upon in one of his final interviews).

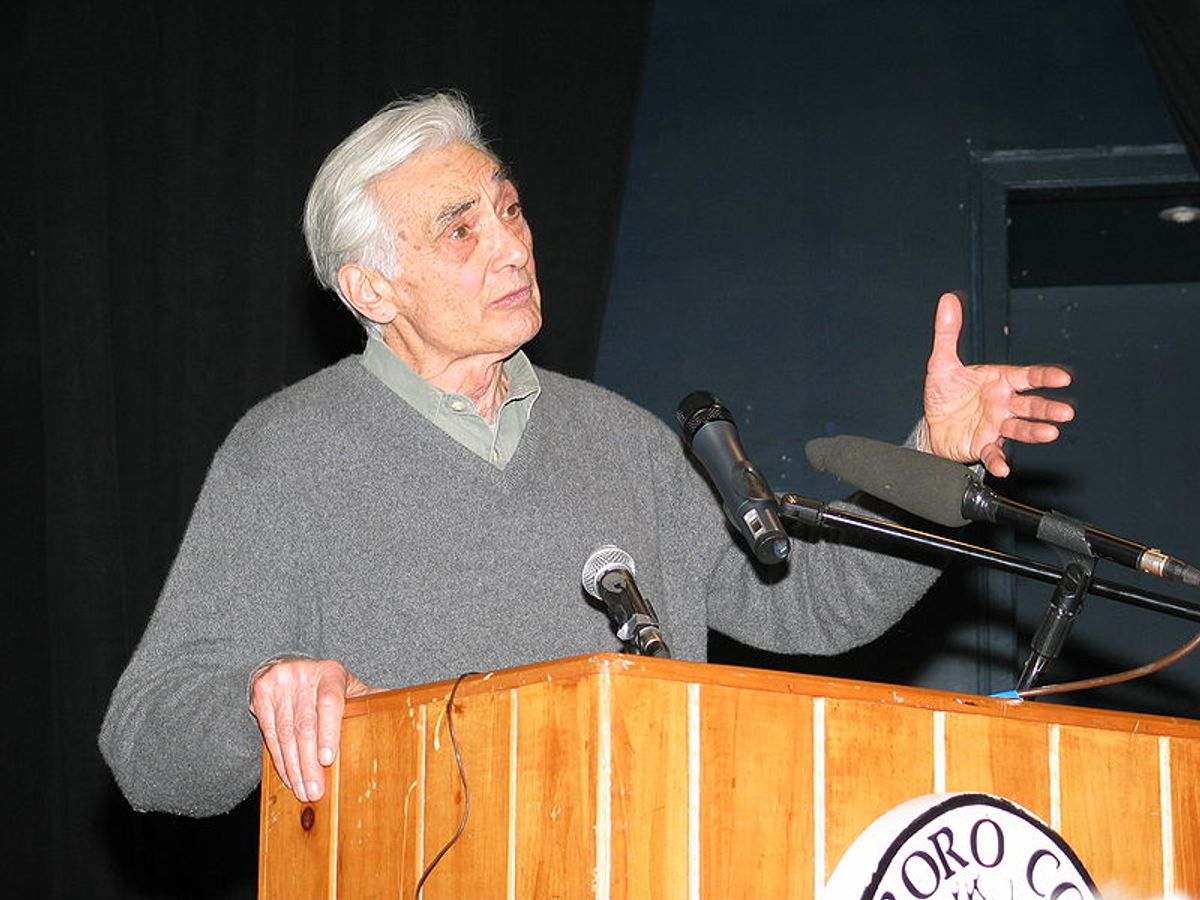

It’s a belief that led Zinn beyond the safe confines of academia. A former union organizer himself, he was unrelenting in his work for organized labor, and on his last day before retiring as a professor, he led his students at Boston University out of class to join a picket line. He taught at the historically black Spelman College through the Civil Rights Movement, and worked and wrote on its behalf tirelessly. He was one of the earliest prominent advocates of withdrawal from Vietnam, and traveled to Hanoi to lobby for the release of American POWs. His commitment to human rights was such that he, a former bombardier during World War II, even researched his own old bomb runs over France to discover the civilian deaths he was personally complicit in.

But Zinn’s humanitarianism was also fuzzy-headed. "A People’s History of the United States" -- the one work among his many for which he will be most remembered -- does not offer a compelling explanation of past events or present conditions. Zinn was not really capable of doing so, committed as he was to insisting on the nobility of the exploited many at the hands of a nefarious few. Exploitation and protest, domination and resistance are indeed enduring and central features of American history (and all other history). But they don’t come near being the whole story. Despite the brave struggles of workers, women and minorities, American capitalism remains astonishingly rapacious, and patriarchy and sexism are still very much with us. And as for racism -- well, it’s clearly survived the election of our first black president in reasonable health. As the historian Robert Norrell has put it, there is still no socialism in Reagan Country.

Zinn’s world had little room for workers who wouldn’t join unions, or black people who were not on the front lines of protest. It’s certainly possible to explain these phenomena without abandoning radical criticism or arguing that the proletariat is cheering on Goldman Sachs. But Zinn’s preference was to pretend there was no issue at all.

It’s for this reason that "A People’s History of the United States" -- and Zinn himself -- might best be compared to physicist Niels Bohr and his theory of the electron. Bohr argued that electrons orbited nuclei like planets around the sun. This is incorrect, just barely, but the theory's simplicity means it's often how students are first introduced to the issue.

I have a second friend who’s had an intense encounter with Zinn, of a kind. This guy never exchanged letters with Zinn; he assigned "A People’s History" to his all-black class of 11th-graders in the Bronx. These kids had never heard American history told at the atomic level, and when they did, it was a revelation. It remains shocking how few people understand that American slaves seized their own freedom at least as much as Abraham Lincoln benignly handed it down to them. Entirely forgotten to us now are the details of how workers in mines and mills survived quasi-feudal conditions, living in company houses, paid in company scrip, policed and surveiled by company goons -- and how they claimed autonomy in often bloody and horrifying confrontations. Because for all Zinn’s flaws, he got these basics right: the American people have genuinely made their own history, for good or ill. And if he couldn’t acknowledge the dark sides of that fact, he still reminded generations of students of the immense, electrifying power they can have as ordinary citizens.

Shares