Would J.D. Salinger have been able to appreciate the great irony of his death -- that no one will welcome it more than those who regard him as their favorite author? Hints and rumors about the piles of unpublished writings stashed in his retreat in Cornish, N.H., have tantalized Salinger fans for decades. The man himself was the primary obstacle between his followers and those works; only with his passing on Wednesday do the manuscripts have the slightest chance of seeing the light of day.

Despite his elusiveness, Salinger succeeded at locating himself at the exact intersection of several kinds of American ambivalence. He was famous for not wanting to be famous, sought after primarily because he did not want to be found. His success made his seclusion possible; his seclusion made the hordes of would-be biographers and interviewers and memoir-writing past associates even more frantic to expose him to the public eye. He created profoundly alienated characters with whom millions of readers have identified.

The work itself seemed to eat its own tail. Salinger, who lived to the ripe old age of 91, wrote about young people who could hardly bear the breath of the world on their exquisitely sensitive skins. His most famous creation, Holden Caulfield, railed against the hypocrisies of adults -- "phonies," each and every one. Seymour Glass, in "A Perfect Day for Bananafish," kills himself after an encounter with a little girl on a beach presses home the corrupt venality of his wife and the rest of the adult world. How does any artist so preoccupied with the purity of childhood cope with growing up?

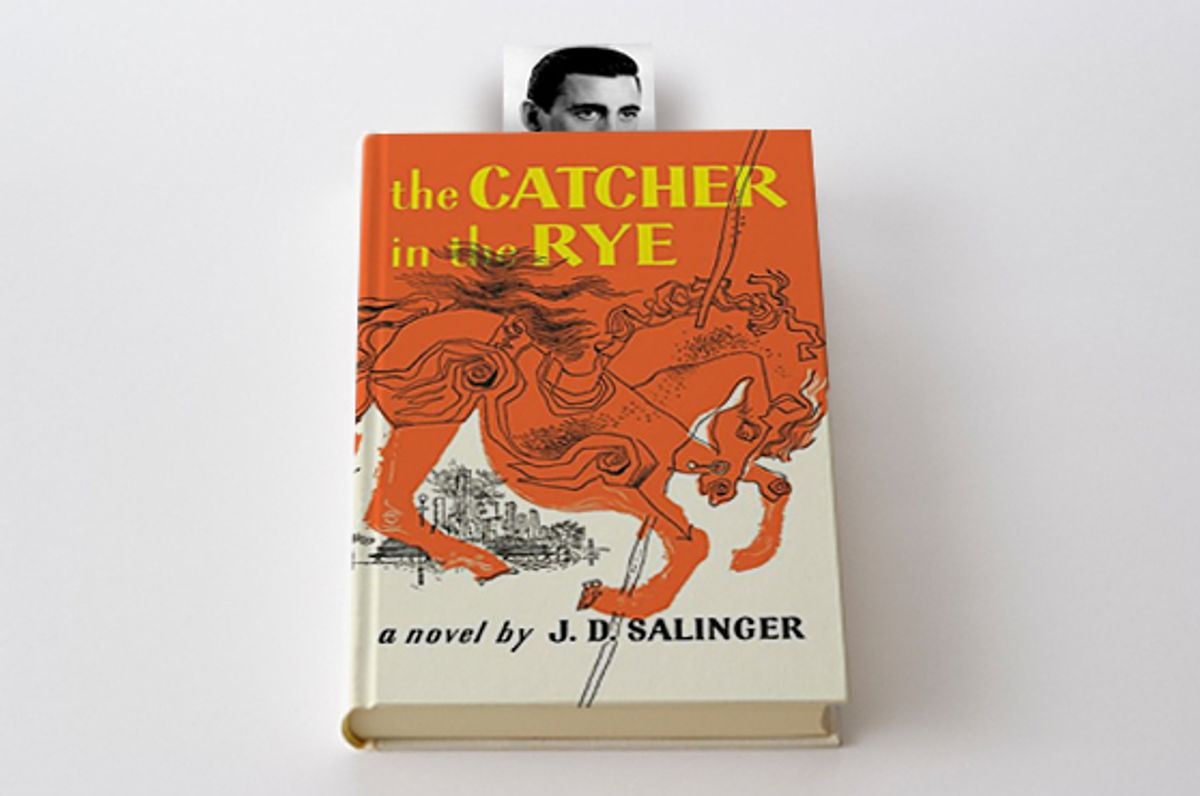

We may never know -- there's no guarantee that Salinger's heirs will find anything of merit to publish in the papers he leaves behind, and, more to the point, Salinger gave no signs that he ever did really grow up. He's the quintessential mid-20th-century American author, and "The Catcher in the Rye" was the archetypal novel of the 1950s, precisely because of its callowness. By comparison, "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," its 19th-century counterpart, seems fantastically worldly.

In "Catcher," every motif of America's famously adolescent national character burns bright: the moral absolutism, the inchoate chafing at any manifestation of authority, the romanticizing of innocence and childhood, a certain prudishness, and the conviction of personal exceptionalism. All of these traits are problematic, obviously; you can see the seeds of countless political mistakes and miscalculations in Holden's self-righteousness and rigidity, his ability to feel persecuted in the lap of privilege.

Yet for all these insufferable qualities, Holden spoke in an authentic American voice: frank, funny and with an infectious vernacular swagger. Salinger admired Hemingway, but he was in large part responsible for liberating American fiction from the austere, humorless sobriety of the Hemingway cult. No contemporary, first-person narrator would ever be the same after "Catcher" -- and thank God for that. Writers ranging from Pauline Kael to Michael Chabon have roamed freely across the frontier that Salinger opened up.

Above all, Holden is a believable teenager, a character who has shown young readers throughout the world that they can find their gripes, their restlessness, their idealism, and their lives breathing in the pages of a book. Though Salinger connoisseurs often swear to the superiority of the Glass Family stories, this is rightly regarded as the author's greatest gift to literature. Holden never grew up, and perhaps his creator never accomplished that either, but most of his readers did. Thanks to "The Catcher in the Rye," they did it with the certainty that a battered paperback tucked in the back pocket of your jeans is an indispensable ally for anyone heading out into the world.

Shares