Objectively speaking, Alexandra Penney has a sad story to tell. Until last December, the former Self magazine editor in chief and author of "How to Make Love to a Man" was working as an artist and living a comfortable life in her Manhattan apartment. Then one night, as she was preparing a dinner party for her friends, a call came: Bernie Madoff, with whom she had invested nearly all of her money, had been running a Ponzi scheme.

In the days that followed, as she struggled to make sense of the news that her savings had disappeared, she agreed to write a blog called the "Bag Lady Papers" for the Daily Beast, Tina Brown’s online venture, chronicling her newly frugal lifestyle. Despite the tragedy of her circumstances, her blog enraged a tremendous number of people. Maybe that's because "tragedy" for Penney isn't exactly the stuff of soup kitchens: She wrote about riding the subway for the first time in 30 years, her baffled trips to Popeyes, "where giggling 4-year-olds are gulping down Coke from quart-sized plastic cups," and her reluctance to give up Carmina, her maid.

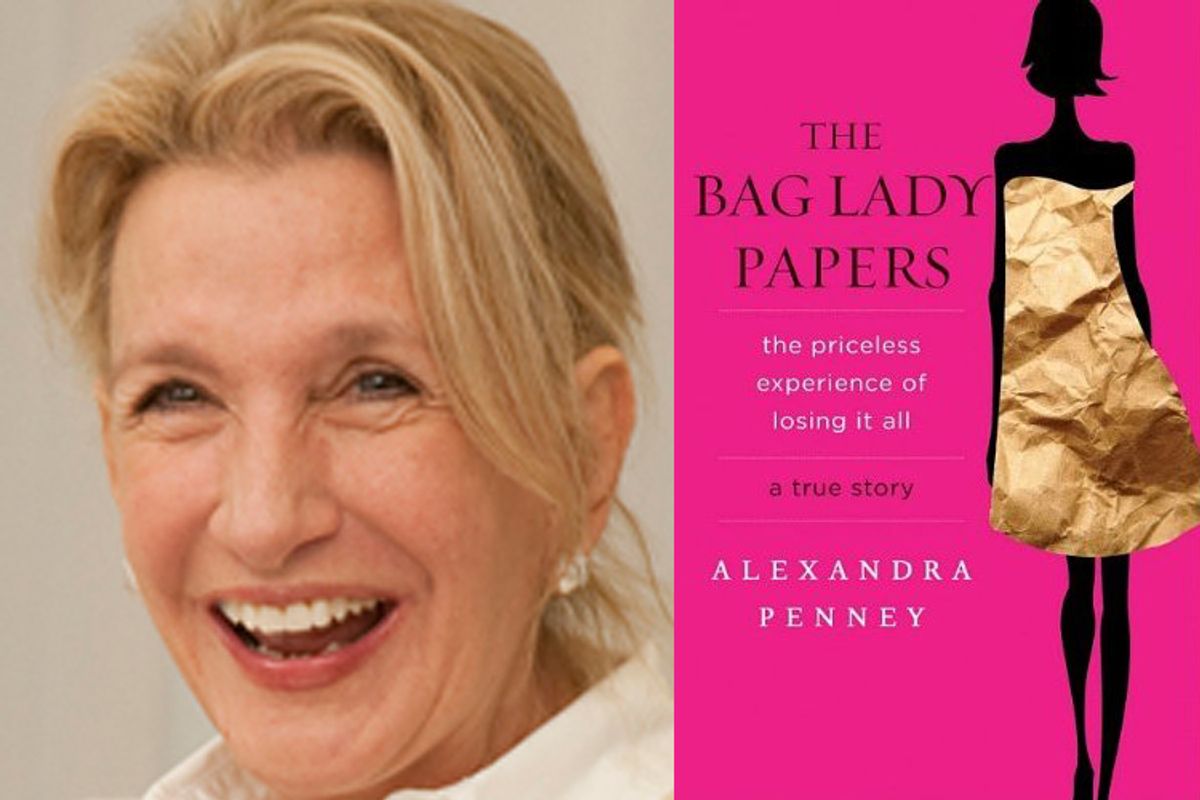

At a time when people were losing jobs and homes, Penney’s complaints seemed not only tone-deaf but deeply offensive. Commenters lashed out at her "pathological lack of perspective on real human suffering," and Gawker called her "the most delightfully un-self-aware ex-rich blogger evah." Now, despite the uproar (or probably because of it), Penney has come out with a book, also called "The Bag Lady Papers," recounting her plight. "The Bag Lady Papers" is a well-written, if somewhat incoherently structured, work that tells the story of one woman’s attempt to come to terms with her financial loss by writing some often very aggravating things.

Salon spoke with Penney over the phone about Tina Brown’s agenda, the nastiness of Web commenters, and how she’s adapting to taking the subway.

How did your blog originally come about?

After the Madoff scandal happened, I had to figure out how to make instant money to pay the bills. I wasn’t even thinking of the mortgage. I was thinking electricity. And luckily, the day after this whole Madoff thing happened, I called an agent of mine from years ago and said I need work. He called me back and said, "Tina Brown wants you to do a blog."

Did you know Tina Brown personally?

I knew her from my time working at Condé Nast, but I hadn’t been in touch with her. She just said, "Write how you feel." Looking back at it, I might not have been so raw. It was just straight out of the gut, and it hit a nerve. There were these vitriolic comments: I was an elitist rich bitch, I was out of touch, I was greedy, I should be cornholed in an alley, I should get cancer. And I just stopped reading them. I am so lucky compared to these other Madoff people, and the people in Haiti, of course, but a personal loss is a catastrophic experience because I’ve worked all my life.

Do you think Tina Brown wanted to make you into a target?

I don’t think so. I'd never written a blog, and I didn't know that the comments tend to get a little crazy. It got to the point where people were fighting among themselves and calling each other Nazis. But the vitriol also contributed to the buzz, which led to the book.

There were some nice comments, obviously. Paul Theroux, someone whose work I really admire, wrote me and said, "You know, this is really straight from the gut, it’s honest, it’s simple, it’s really what you feel, keep going." And he’s not even a friend. I was bowled over.

Most of the angry comments accuse you of being tone-deaf. Did you think their complaints are valid?

Millions and millions of people are worse off than I am. I don’t forget that. I think there's been this enormous change happening in society, a recalibration and a rethinking of what money means. Look at the absolute anger and rage at the bankers and at Goldman Sachs. I can understand somebody saying, "Hey, this woman had 40 shirts," and I can really understand that. It’s like: Who does she think she is? But I had those shirts since college, and I made all that money myself, every dollar, and to have it stolen is an unbalancing experience.

It seems a little callous to call something "The Bag Lady Papers" when there are people out there who are actually losing their homes.

It’s a very good point. But my entire life, save from when I was 16 or 17, when I first started working, I had a fear I would end up on the streets, even though I come from a comfortable background. It was a real fear, and I went into therapy and still couldn’t get rid of it. "The Bag Lady Papers" came from those fears.

Didn't anybody warn you about the title?

To me it was always about my bag lady fears. It's a fear that men don't have, by the way. It comes from distant parenting or childhood abandonment. I had that. It's what happens if you don’t have a nurturing environment as a child, and you think this could happen, that you're going to end up on the street.

But I see what you mean. There is an aura to that term that could be negative. All I can say to that is, it was the truth. What am I going to do, lie? Or do something that’s going to sell copies of books? I don’t know how to do anything else but be direct. I think your point is well made. I didn’t even think of it.

The day after all of this happened, I was not thinking. I was just panicked. Really traumatized. I was heading to be a bag lady. I considered suicide.

You mention that in the book, but I thought it was a joke. You really considered suicide?

I was like, I’m going to get old, indigent, sick. I’d rather not live that kind of life. Richard Avedon had once told me about this Hemlock Society online, and we’d have long conversations about that. I went to the Hemlock Society Web site to see what that was, and even the Hemlock Society had disappeared. At a certain point it’s all absurd.

I blame the FCC and the IRS for Madoff. It’s not about sympathy; it’s about doing something. My situation doesn’t call for pity.

But to me, the book does often come across as a plea for sympathy.

I felt sorry for myself, but it certainly wasn’t a plea for sympathy. I found resources I never thought I had. I had to take a few tranquilizers, but I was fine. I learned a lot. I learned not to dwell on things, to get past them. I was writing this book in the morning, and I worked on my photographs. I take pictures of blowup dolls, and I use them as ciphers to comment on society, about sex and consumerism, to comment about artifice and superficiality. In my pictures, the dolls just started committing suicide. One doll's Mercedes was repossessed.

You’ve also been a target of sites like Gawker and New York magazine. Did you read what they wrote about you?

I had a friend of mine who said, "Why don’t you do a Google Alert? Whenever something is mentioned about you, you’ll know," and I said, "You know, I’m really trying to make art." I didn’t want to know what people thought. If you don’t have a dollar you don’t have time to loll around on the Net.

What’s the biggest thing you’ve had to give up since the Madoff scandal?

I used to have Starbucks coffee. I used to have manicures. No big thing I miss. Maybe getting an updated computer? I still take taxis sometimes, like when it was freezing cold the other night. I’ve given up cut flowers. Travel, I guess?

What about your maid, Carmina?

I have said that I would never give up Carmina. She comes two hours a week, sometimes four. She was working three, four days a week before. She needs the money from me, so whatever I make, I try to give her money as well. I can clean and iron perfectly well myself, but she couldn’t find other work. She’s part of my family.

You’ve written about having to take the subway for the first time in 30 years after you lost the money. How's that going?

I hate the subway. I think it’s the worst thing. But I’ve gotten into buses. I actually get a lot of work done on buses, since I've kept my BlackBerry.

Are you worried about the reaction to the book?

No. It’s out. What am I going to do about it? Take it back? There will probably be a lot of horrible reactions, but isn’t that just the nature of the Net?

Shares