Morgan Freeman hasn't just played God; he actually is the voice of God. He has gazed down from heaven upon penguins, narrating the intricacies of their life-and-death struggles; in Steven Spielberg's "War of the Worlds," he reveals, in his all-seeing, all-knowing wisdom, that the invading aliens are dying because they have no immunity to diseases that barely faze humans; and, perhaps most significantly, his is the first voice you hear when you turn on the CBS Evening News. The voice of Morgan Freeman is everywhere; it's like God wallpaper.

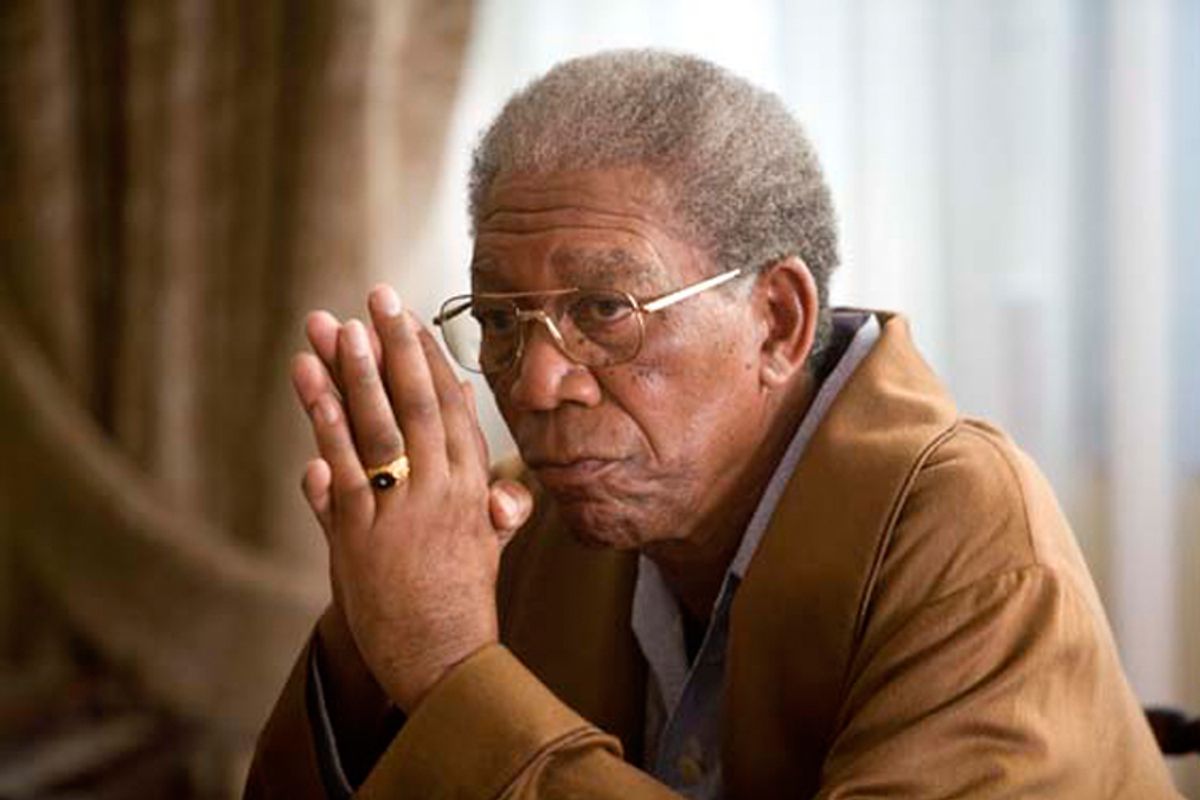

After you've played God — twice, as Freeman has done in Tom Shadyac's "Bruce Almighty" and "Evan Almighty" — and been God, there's not really much left to do, except play Nelson Mandela. Which is what Freeman does in Clint Eastwood's "Invictus," in a performance that starts out plodding and ends up sly. "Invictus" tells the story of how Mandela, after being elected president of South Africa (following a 27-year prison stint), decided to try to unify his deeply damaged country by getting all its citizens — black and white — to rally behind the national rugby team, the Springboks. The country's black population, the majority, sees the Springboks as a relic of apartheid; the National Sports Council even thinks it might be time to abolish the team. But Mandela, recognizing that you can't change a country's future by erasing its past, instead opts to change the nearly all-white team's image in an effort to get the whole country behind it. To that end, he enlists the help of the team's captain, François Pienaar (Matt Damon), who accepts his mission with earnest enthusiasm. Among other things, Pienaar gets the team — grumbling at first — out to play ball with the black kids who live in the townships. In the end, it's not just the team's image that changes, but the team itself, and as the nation responds in kind, Freeman's Mandela — seeing that his nonstrategic strategy has worked — loosens up himself. Freeman's performance actually becomes smaller — more pointed and more focused — instead of bigger, the idea being, perhaps, that this is a man who recognizes that great strides comprise many small steps.

Mandela, who served as South Africa's president until 1999, is one of the most charismatic and respected modern-day world leaders, the kind of figure plenty of actors would love the chance to play. That's where the danger lies: It's easier to play greatness than it is to play a human being, and Freeman, at first, seems to have stepped right into that trap. It doesn't help that Eastwood, not a particularly subtle director to begin with, can't seem to forget he's making a worthy tale of renewal and hope with a massively significant world figure at its center, instead of just telling a good story. The movie's first third is stiff and dull.

And through that section, so is Freeman. He speaks slowly and solemnly; his brow is furrowed with worry befitting a man who's just become the leader of a historically troubled nation. It's not that this isn't a realistic or believable approximation of Mandela himself; impersonation alone doesn't make a good performance. A performer has to cut to something deeper.

And eventually, Freeman reaches that something deeper, not by clamping down on the performance, but by loosening his grip on it. Performances are shaped just as narratives are; although scenes aren't shot in the order in which we see them in a finished movie, a performer still has to bring his character from point A to point B (even if the "point B" scenes are the ones being shot first). What Freeman injects into the second half of "Invictus" is a sense of mischievousness and curiosity: Suddenly, instead of just seeing Nelson Mandela as a great man, we get an idea of how a guy could survive 27 years of unjust imprisonment and, instead of becoming embittered and broken, emerge with a better sense of what makes human beings tick. He has a sense of humor as well as sense of responsibility. At one point we see him learning the names of all the Springboks so he can greet them as if he's been familiar with them all along — that's a diplomatic necessity, not a nicety. But when Mandela actually meets the men on the team, he has a little joke or an unspoken moment of connection with each of them. Maybe what Freeman is channeling here is simply the fact that Mandela has the common touch, the ability to make the person he's speaking to feel like the only one in the room. But Freeman gets the idea across by playing a moment, as opposed to displaying a characteristic. As he chats with those guys — whose life experience couldn't be further from his own — we see pleasure and duty merge. His smile is cautious but impish. He's a fan talking to a bunch of sports stars, not a deeply respected world leader.

It's hard to pinpoint the exact moment in "Invictus" when Freeman lets go of playing qualities — dignity, affability, fortitude — and starts playing a person. When he invites Pienaar to tea — it's their first meeting — he breaks his conversation to greet the older white woman who arrives with the tea tray. "Mrs. Bliss!" he says, in that rolling, velvety voice, "You're a shining light in my day." He then introduces her to the rugby star, because she, also, is a person who matters. Bringing that idea home is just one of the many little triumphs Freeman pulls off in "Invictus," making it a performance of casual warmth instead of a treatise on the idea of greatness.

Shares