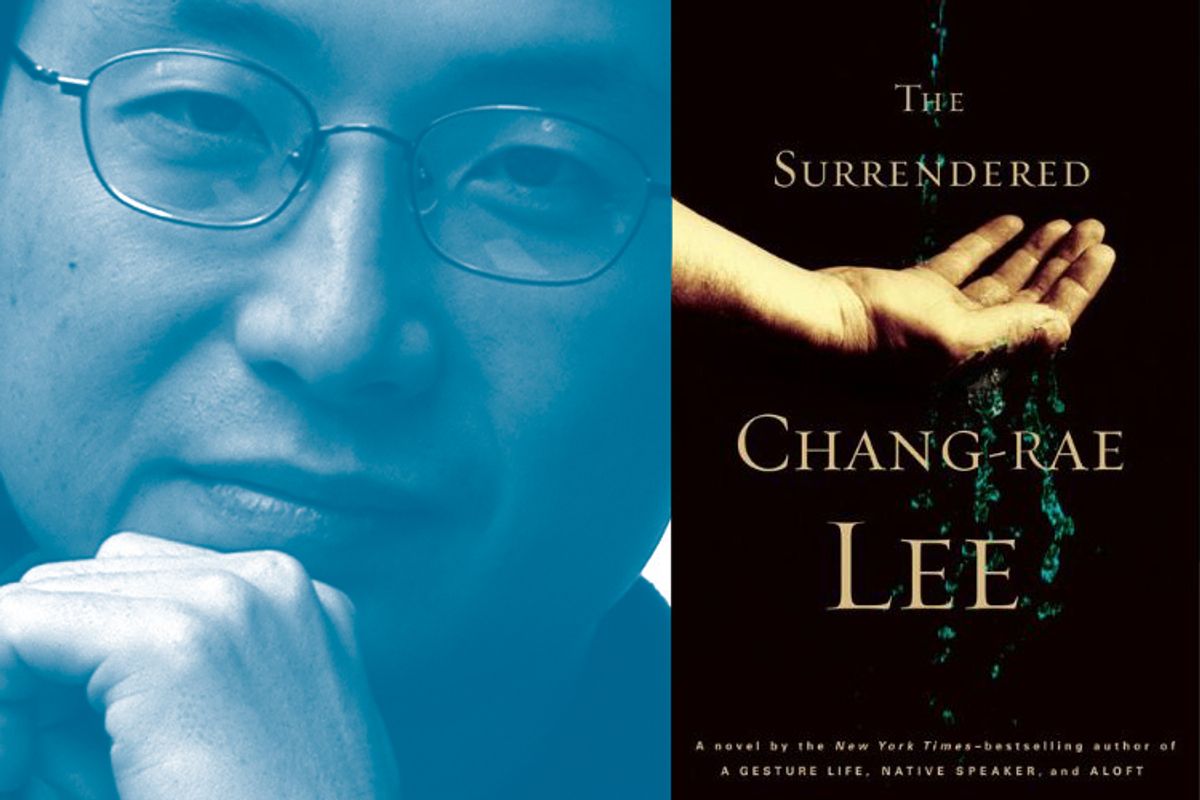

Big novels, like big dogs, are more appealing when imperfectly groomed, and for that reason I approached Chang-Rae Lee's big novel, "The Surrendered," with some trepidation. Lee is celebrated for three earlier books ("Native Speaker," "A Gesture Life" and "Aloft") that describe suburban Northeastern life in the manicured yet lush style of Cheever and Updike, creators of beautifully complacent tales of mid-2oth-century privilege presented as the stories of regular guys. Since "The Surrendered" is about the aftermath of the Korean War, it looked to be an inauspicious combination of two things that the contemporary literary novelist often confuses with high art: stretches of fancy, static prose and bleak accounts of hardship and atrocity.

I won't lie and say that "The Surrendered" doesn't occasionally indulge in either of those two things, but that doesn't wind up mattering, because the narrative sweep of the novel turns out to be irresistible. Characters that shoulder their way into the reader's psyche with an almost alarming vitality and Lee's organically skillful plotting are the powerful engines driving "The Surrendered." It's about survival and its costs, as embodied by two people: June Singer, a well-off Korean-born antiques dealer who is rolling up her Manhattan life in the early chapters of the book, and Hector Brennan, an alcoholic janitor in New Jersey. Hector is, implausibly, the father of June's son, Nicholas, though he doesn't know the young man exists and hasn't seen or heard from June in decades. Nicholas has run off to Europe and disappeared, and June has resolved to barge back into Hector's life, insisting that he join the search.

We learn, from the novel's first chapter, what June endured as an 11-year-old refugee fleeing south from North Korea during the war; she lost her parents, her older brother and sister and finally the younger brother and sister entrusted to her care. All this leaves her boiled down to a flinty core of stubborn will and, Hector thinks, "surely the strongest person he had ever known." Whether June's fearsome will was forged by the war or simply revealed by it is one of the novel's mysteries, but without a doubt it's the reason she made it out of Korea alive, as well as why she prospered afterward.

Hector, on the other hand, is merely lucky, although he doesn't see it that way. He's big and, despite his drinking, still fit, "a shockingly beautiful man," according to June's dispassionate assessment. Hector wins every fight he gets into and his wounds heal with uncanny speed. As a soldier in the Korean War, he stepped away, unharmed, from scenes of carnage. With the name of a classical hero and hailing from the town of Ilion, N.Y. ("Ilium" being another name for Troy), he appears singled out for a glorious destiny, but as Hector sees it, he's cursed to trudge onward even as the people around him are destroyed. As an adolescent, he slipped away for an assignation with a married woman instead of performing his nightly duty of walking his drunken father home from the neighborhood bar; his father fell into a river and drowned. Crippled by guilt, Hector has spent his life believing he was "the cause, and the symptom, and the disease; he was the dooming factor for everyone but himself."

What links this unlikely pair is love, not for each other, but for Sylvie Tanner, the wife of a minister who ran the Seoul orphanage where Hector once worked and June once lived -- even then, at the age of 14, she was a notoriously aggressive loner. Sylvie's story is the third strand of the novel, coming in late and telling of her childhood as the daughter of missionaries so devoted to their cause that she felt "set just outside the centripetal force of their labors, the impassioned orbit of their work." Kind and gentle, she represents, for June and Hector, the possibility of emerging from trauma with one's humanity, and ability to feel for others, intact. How did she end up failing them both?

"The Surrendered" moves backward and forward in time with an impressive smoothness, nosing out the events that led June and Hector to unite, however briefly, and create Nicholas. Just once, Lee stoops to sheer melodrama (there's a car crash in the book's second half that's a bit over the top), but it's an error of daring too much, rather than of settling for too little, and ultimately, it's forgivable. So are the moments, not frequent, when he strains too hard after writerly gorgeousness, clotting up his sentences with an excess of metaphorical flourishes. In a novel so rich in the hearty pleasures of storytelling, these blemishes are almost endearing, the overflow of a welcome enthusiasm. Also, Lee's reaching does sometimes work, as when he describes intimacy's tentative return to the middle-aged Hector's life, thanks to a tender barfly: "With each night she spent, another diaphanous layer of her presence seemed to settle upon him and everything else, the fine dust of her that he could almost taste on a spoon, on the rim of a glass."

But who really reads a novel in search of lovely sentences? What most of us hope to meet on the page are characters who bloom into a persuasive illusion of life, and in June and Hector -- one strong of will, the other strong in body -- Lee has most definitely succeeded. It's impossible not to want to know how they came to be the way they are or how they will end up. They may struggle to go on caring, but we don't have to.

Shares