At this point, the idea of somebody publishing an attack on Charles Darwin isn’t exactly surprising. The 19th-century naturalist, and the man behind the theory of evolution, has never been a particularly popular figure among conservative Christians, and, these days, the anti-Darwin movement is a cottage industry. In the last year, which marked the bicentennial of Darwin’s birth and 150 years since the publication of "The Origin of the Species," the man was even subjected to the peculiar indignity of an assault by former "Growing Pains" star Kirk Cameron.

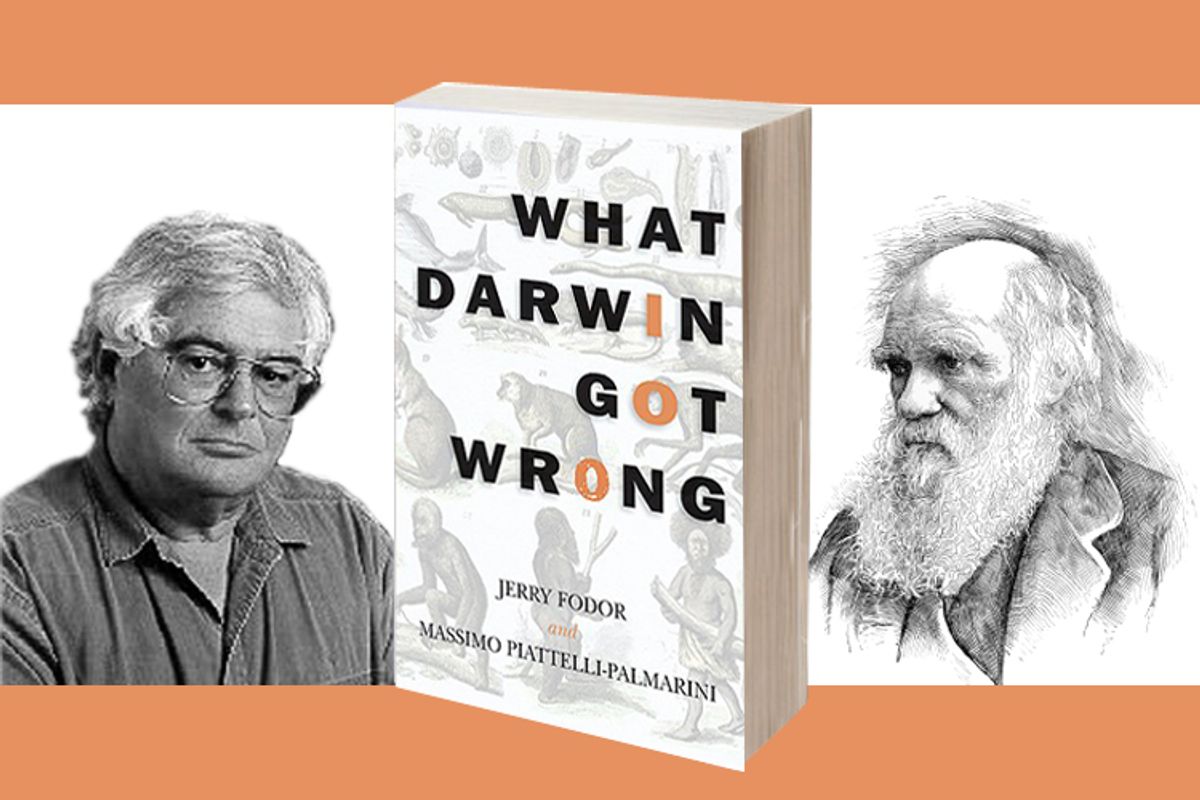

But unlike most of these attacks, "What Darwin Got Wrong," a new book by Jerry Fodor, a professor of philosophy and cognitive sciences at Rutgers University, and Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, a professor of cognitive science at the University of Arizona, comes not from the religious right, but from two atheist academics with -- surprise -- a nuanced argument about the shortcomings of Darwin’s theories. Their book details (in very technical language) how recent discoveries in genetics have thrown into question many of our perceived truths about natural selection, and why these have the potential to undermine much of what we know about evolution and biology.

Salon spoke to Fodor over the phone from his home, about the problems with Darwin’s ideas, bloggers’ "obscene" comments on his work, and why Darwinism might be as unreliable as creationism.

In 2007, you wrote an article attacking Darwinism in the London Review of Books, and experienced a lot of backlash from both inside and outside of the scientific community. Why do you think people get so worked up about Darwinism?

It’s a theory that’s played all sort of roles in the foundations of biology. There’s a lot of people who think wrongly that if you didn’t have Darwinism the whole foundations of modern biology would collapse. I doubt that’s true. I’m sure it’s not. But if you tell people, "There’s this fundamental theoretical commitment you’ve made and there’s holes in it," they’ll want very much to defend that theory.

Most of the backlash to the book so far has been on blogs, which have been pretty obscene and debased. What’s upsetting is that they tell you that they think you’re an idiot, but they don’t tell you why -- people who aren’t part of the field or who may not, in many cases, know much about Darwin. I’m not sure that all people who have been blogging about it are very sophisticated. It’s frustrating because you don’t know who you’re talking to.

At some point you just have to stop worrying about the reaction and worry if the argument is any good. I don’t take the arguments that say, "This that can’t be true because of what I learned in Biology 101" very seriously.

What is your beef with natural selection?

The main thing Darwin had in mind with natural selection was to come up with a theory that answers the question, "Why are certain traits there?" Why do people have hair on their heads? Why do both eyes have the same color? Why does dark hair go with dark eyes? You can make up a story that explains why it was good to have those properties in the original environment of selection. Do we have any reason to think that story is true? No.

According to Darwin, traits of creatures are selected for their contribution to fitness [likelihood to survive]. But how do you distinguish a trait that is selected for from one that comes along with it? There are a lot of interesting structures in creatures that have nothing to do with fitness.

Some variants in selection are clearly environmental. If you can’t store water you’ll do worse in a dry environment than if you can. But suppose that having a high ability to carry a lot of water is correlated for genetic reasons with skin color. How do you decide which trait is selected for by environmental factors and which one is just attached to it? There isn’t anything in the Darwinist picture that allows you to answer that question.

So we have no way of knowing whether a trait serves an evolutionary purpose?

Some traits are presumably selected for by the environment, and some of them are not. If somebody says Trait A affects fitness and Trait B does not, but Trait B comes with Trait A so you’ve got both traits in the organism, it’s very natural for somebody in the Darwinian tradition to think that Trait B has been selected for by the environment. But the answer is, it’s not there for anything.

Look, everybody has toenails, so you might ask yourself, why is it such a good thing we have toenails? It may be a case that in the environment there was some factor that favored toenails but there also may not.

As you explain in the book, it turns out many genes are far more tied together -- and gene expression is much more complicated -- than many people originally thought.

What the genetics has come to show is that traits are not independent, but complexly interconnected, and a lot of the effect that the environment has on an organism’s evolution depends on what organism it is.

There’s a famous fox-into-dog experiment, in which many generations of foxes were selected for being domestically trainable. As you would expect, when you select for domesticability, you get animals that behave less and less like their feral counterparts -- but you also get curly ears and kinked tails and changes in their reproductive system. Nobody had that in mind, but the structure of the organism groups all of these traits together. Why do these animals have kinky tails? They just happen to be structural correlates. Now the question is, how much of the evolutionary variance is determined by factors of the environment and how much is controlled by the organization of the organism, and the answer is nobody knows.

Most children learn about natural selection by learning the example of the giraffe’s long neck, which supposedly evolved because it allowed animals to graze higher branches. Does this mean that we’re giving schoolchildren the wrong information?

The inference runs that there’s this creature that has a long neck, so this creature was selected for having a long neck. That inference is clearly invalid. A creature that has a long neck may have that neck because a different trait was selected, and the long neck came along with it.

And in a sense, there are no such things as traits. The environment selects creatures. Animals can have long necks and toenails, but if you try to break such creatures apart into traits and you say, OK, "What selected this trait?" and, "What selected that trait?" you've made a mistake right from the beginning. The disintegration of the organism into traits is itself a spurious undertaking. Biologists have said for a long time that organisms aren’t like Swiss apples, you can’t tap them on a table and have them fall apart into distinct wedges. Selection is operating on whole organisms.

There's been increasing evidence in recent years that homosexuality has a genetic cause, which doesn’t exactly mesh with natural selection, given that gay people aren’t likely to have lots of children. Does your theory help explain the gay gene?

It’s not obvious what, when the environment was selecting for fecundity, would have selected for people who are gay. You could have gotten them innately as a result of something that has nothing to do with sexual performance.

Do you think people are defending Darwinism because they think any attack on Darwinism gives power to creationists, and they don't want creationists to get the upper hand?

I think there’s the sense that if you think that there’s something wrong with the theory you’re giving aid and comfort to intelligent design people. And people do feel very strongly about whether you want to do that.

When you do science, you try to find the truth. The problem with creationism, even if you’re not a hardcore atheist, as I am, is that anything is compatible with creationism. If God created the world, he could have created it any way he liked. So creationists, when faced with evidence of evolution, are happy to say that that’s the way God created the world. If it turns out that there is no process of evolution, they’d say OK, that’s fine too. Whatever turns out to be the case it’s compatible with God having created the world, so you can’t argue with their position or you throw your shoulders out.

As you explain in the book, one of the problems with Darwinism is that Darwin is inventing explanations for something that happened long ago, over a long period of time. Isn’t that similar to creationism?

Creationism isn't the only doctrine that’s heavily into post-hoc explanation. Darwinism is too. If a creature develops the capacity to spin a web, you could tell a story of why spinning a web was good in the context of evolution. That is why you should be as suspicious of Darwinism as of creationism. They have spurious consequence in common. And that should be enough to make you worry about either account.

If you're right, what do you think your argument means for the study of evolution?

If this is true, then we need to rethink the implications of Darwinism. Maybe the right question to ask is not what environmental variables are doing selection, but what kinds of complexes are they selecting on. One sees, even without God, how this Darwinian story could turn out to be radically wrong. You could see a massive failure of the evolutionary project, because wrong assumptions were made.

Shares