Since the Academy Award for animated features was created in 2001, the category has been dominated by big-budget, computer-animated films from a handful of studios and distributors, mainly meaning Pixar (six nominations and four wins, in eight years), Walt Disney and DreamWorks. There were exceptions -- Hayao Miyazaki's hand-drawn "Spirited Away" won in 2002, and Nick Park's stop-motion "Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit" in 2005 -- but those almost seemed to underscore the wider world of innovative animation Oscar was ignoring. Over the last several Oscar seasons, the roster of nominated films has seemed so predictable and unadventurous that some commentators have suggested abolishing the category.

Nobody's saying that this year. While Pixar's "Up" (also nominated for best picture) is considered the likely winner, it's definitely nothing like a formulaic kid-flick -- and it's also the only computer-animated film among the five nominees. After more than a decade of CGI dominance, handmade is suddenly all the rage: Even Disney's nominated "The Princess and the Frog" was hand-drawn, as if in a deliberate effort to suggest that company's great tradition. Nominees also include two stop-motion literary adaptations aimed at a kidult crossover audience, Henry Selick's "Coraline" and Wes Anderson's "Fantastic Mr. Fox."

But those movies had all been widely seen, favorably reviewed and discussed as possible Oscar fodder. Nobody, and I mean absolutely nobody, was prepared for the nomination of "The Secret of Kells," a dazzling, not to mention utterly charming, hand-drawn fable about a 12-year-old boy's adventures in early medieval Ireland. "We thought we might be in line for some Irish and European awards, and that would be that," says director Tomm Moore. "The Oscars? No way. That never entered my mind."

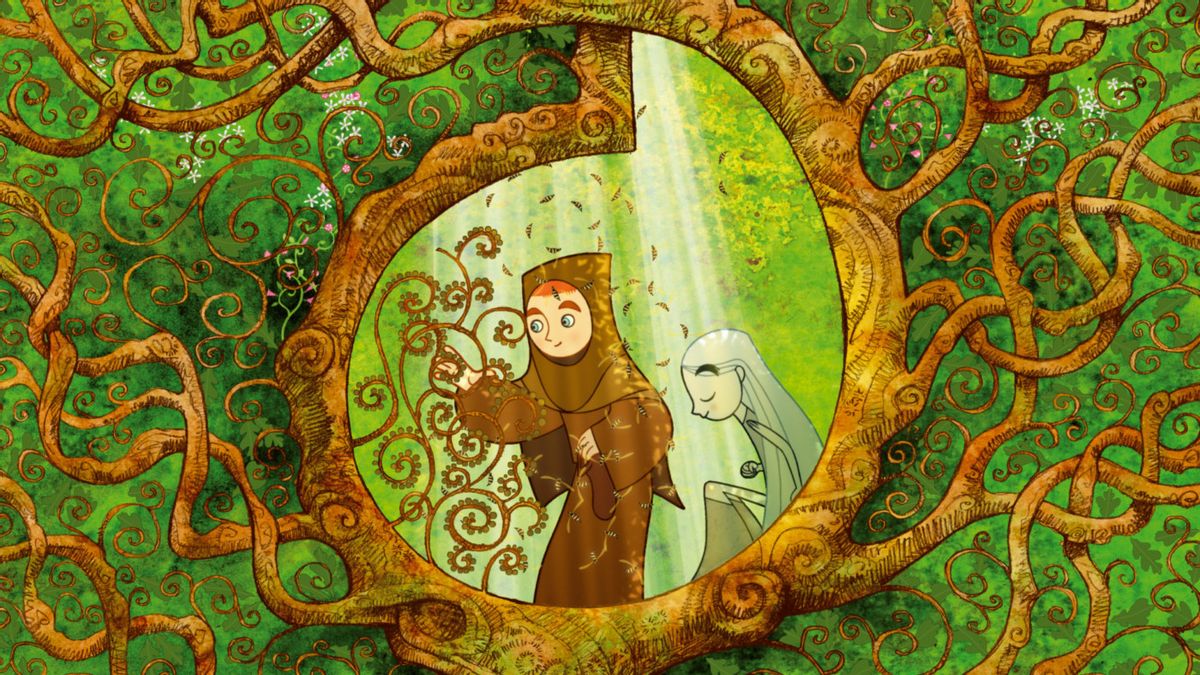

A haunting blend of history, fairy tale and pure invention, Moore's film follows a young student monk named Brendan, who has spent his whole life inside the fortified walls of the Abbey of Kells, whose forbidding abbot (voiced by Brendan Gleeson) has built it as a sanctuary against the Viking raiders who are pillaging and burning Irish villages at will. (It's somewhere around the year 800 A.D., give or take.) Into Brendan's cloistered life comes a playful monastic wanderer named Aidan (Mick Lally), who apparently studied with the legendary St. Colum Cille (aka St. Columba) on the Scottish isle of Iona, and carries with him perhaps the single greatest treasure of medieval Ireland.

That treasure is neither gold nor jewels but a book -- a lavish illustrated manuscript version of the Gospels that in centuries to come will be known as the Book of Kells. (Today it is considered Ireland's most important single cultural artifact, and can be seen under glass in the Old Library at Trinity College in Dublin.) Brendan's yearning to help Aidan complete the manuscript, and safeguard it from Scandinavian marauders, leads him outside the walls of Kells into the magical forest around it -- and also out of the then-new Christian world into the pagan past.

Borrowing a wide range of illustrations and motifs from the Book of Kells and numerous other medieval and indigenous sources, Moore and his team of Irish, Belgian and French animators send Brendan on a mystical voyage. He is aided by an irrepressible forest sprite named Aisling ("ASH-ling"), but must go alone to face the terrifying Crom Cruach, an ancient and perhaps demonic Celtic deity who -- at least in some legends -- required the sacrifice of first-born children to ensure the harvest.

All this is a freewheeling and fanciful blend of art and legend; Moore doesn't pretend to offer a historical account of how the Book of Kells was created, or a coherent version of the collision between paganism and Christianity in Ireland. Rather, "The Secret of Kells" is a gorgeous transcription of medieval decorative art and its themes into a contemporary animated narrative, one that should enthrall children older than 8 or so, along with the adults lucky enough to watch with them. (My guess, so far, is that the invading Viking hordes and the Crom Cruach sequence are probably too scary for my 6-year-old twins. They have a difficult time with the evil stepmother in "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.")

American distribution rights for "The Secret of Kells" belong to GKIDS, an independent producer and distributor of children's entertainment whose main property is the New York International Children's Film Festival. To its credit, the company responded to the unexpected Oscar nomination by pushing the film into one New York theater this weekend, with wider release and a DVD version soon to follow. I had hoped to meet Tomm Moore in person during his New York visit, but both of us were snowed in after the recent blizzard and decided to talk on the phone instead.

It's such a wonderful idea for an animated film, but also a pretty unlikely one. Tell me how and when you came up with it.

I had an idea along these lines when I was in college in '99, and I started to develop it with a group of friends -- the idea of trying to translate Irish art, Celtic art, into animation. To do something along the lines of, say, what they did in "Mulan" with Chinese art.

After I got out of college we set up an animation studio in Kilkenny and we were doing commercials and other kinds of jobs. So this was a pet project we could never get off the ground until 2005, when we met the producers of "Triplets of Belleville" [the French-Belgian animated feature, Oscar-nominated in 2003]. We were able to put the financing together and work on a final script. We had many years of development prior to that, in terms of the art style. But in 2005 we were finally able to hit the ground running.

Talk about the art style. Obviously you drew on the Book of Kells itself. Was there other medieval art, or art from other periods, that you looked at?

At a certain point it was the Book of Kells itself, and then we started looking at medieval art in general, the triptychs and other things. Basically anything in and around that whole era -- European medieval art and also anything involving indigenous folk art that had been translated into animation. We looked at, like, the Hungarian folk-tale series that had been done in Eastern Europe, where they had taken Hungarian art and animated that. Or American things like "Samurai Jack," where they'd taken Japanese and other indigenous art and adapted it into TV animation. We took all of that as reference points, and tried to come up with our own style.

I know this is a work of fiction, not history. But how much research did you do? Did you want to paint something close to an accurate portrait of that era?

We started off with a fairly dry version of the story, which was even a little bit too historical. Then we started working with a screenwriter named Fabrice Ziolkowski, this French-American guy, and he helped us tease out more of the hero's-journey story. That opened it up to allow us to bring in some of the legends and fantasy that surrounded the history, which might have made the story skew a little bit younger, and also made it a bit more fun for the animators doing it.

Telling the story through this young boy, who's a kid but also a monk -- or, I guess, a student monk -- was an interesting choice.

We were always telling the story through Brendan's eyes, but I think I was looking too much at Aidan and the Abbot in the first draft of the script. Seeing the world through Brendan's eyes is much more interesting. Imagine the suggested world of a kid in the Middle Ages who's never been outside the walls of this abbey -- that gave us another way of looking at the whole movie. So he became central rather than secondary.

Was the Abbey of Kells really this kind of fortified bulwark, the way you portray it? Is that part historical?

Yeah, basically it is. The land was given to Cellach, who was a historical character, by a local nobleman. Iona had been burned out and sacked so often that they decided to come into the center of Ireland [County Meath, roughly 40 miles north of Dublin] and try to get away from the Vikings. Of course the Vikings just came up the rivers and wound up sacking Kells in the end anyway. Maybe the walls weren't that big! We exaggerated that a bit, now.

It's fascinating that you depict the monks at Kells as being not just Irish, or not even principally Irish, but as coming from all over the world -- Italy, Africa, the Middle East. What's the historical basis for that?

Well, this is what we found most interesting and surprising when we did research into the Book of Kells. One of the things they don't understand is that there are inks and patterns and designs in the Book of Kells that come from all over the world. There's some ink that seems to have come from Afghanistan; there are patterns they've linked to Morocco. It's fascinating stuff: They've found bones of pet monkeys, things like that. Stuff we didn't even use in the movie. There was a lot of trade and interaction, a lot of people coming to Ireland from mainland Europe for refuge. Maybe it was all down to trade and dialogue, and maybe there were all sorts of people from all over the world living in Ireland at the time. We thought it was a nice reflection of how cosmopolitan Irish society has become today.

Right. As you and I both know, Ireland in the 20th century was, at least at times, a pretty provincial place, somewhat cut off from the world.

I grew up in an Ireland where basically all my friends were Irish people with good Irish names, all of that. My son now goes to an Irish-speaking school where he's got friends from Burma, Poland, you know, everywhere. So I thought it was interesting to see that in the Middle Ages Ireland had an influx of people from everywhere, which parallels what's been going on just in the last 10 years.

Wait -- your son goes to school with Burmese and Polish kids who are learning Irish?

Yeah.

That's fantastic! I wish my dad, who was a Celtic scholar, was still around to see that. It seems like you're trying to address the old-style Irish nationalist stereotype, the idea that there was some pure culture that had been handed down from ancient times.

Ah, no. We're a mongrel breed and that's for sure. A lot of Irish people are surprised by how rich a cultural history we had around that time.

Talk about the way you use the pagan and pre-Christian iconography in the movie, especially the ancient Celtic god Crom Cruach, whose image was supposedly destroyed by St. Patrick.

What I found most interesting about that period -- I've done a couple of graphic novels about St. Patrick, and what I really learned was how the ancient Celtic gods had been transmuted into the new Christian pantheon. A lot of the saints, like St. Colum Cille, had all these amazing legends around them: His hand glowed, so he could write at night! All this strange stuff. It would always be this confluence of the old pagan beliefs and the more modern -- well, not modern -- but the newer Christian stuff.

I found that the Crom Cruach story seemed to be linked to this old duality, with Lugh as the sun god and Crom as the god of the underworld. There were all these legends about human sacrifices that St. Patrick stopped by defeating Crom Cruach. I sort of thought, maybe that's where the idea of the snakes being driven out of Ireland came from, St Patrick defeating Crom. Even though Crom is most often represented as a worm or a giant, a giant idol, we picked on serpent. We thought there was symbolism we could use from the Book of Kells, where they have all these Ouroboros, these snakes eating their own tails, going around the pages. So we thought, let's make Crom into something Brendan imagines after seeing some of the Book of Kells.

And then there's Aisling, your little forest sprite. Where does she come from?

I don't know if you know much Gaelic, but Aisling means "dream," and there's this tradition of Aisling poems, more from the Celtic Revival period, you know, the William Butler Yeats era. They used to write these poems where Aisling would be a girl the poet would see, who would tell tales about Ireland's woe or whatever. We thought it would be fun to make her a little girl rather than a woman, make her this symbol of the matriarchy that Christianity was replacing, but also something like a little sister to Brendan. I based her on my own little sister, you know? She's always trying to best him, and she's got all these powers. Because she's a fairy she can transform into any creature. She's kind of a mixture of this wise old pagan deity and a pesky little sister.

Tell me a little bit about the techniques and technology you used. This is all hand-drawn animation, or mostly?

The animation is 95 percent hand-drawn. We did 20 minutes of animation in Kilkenny, and that was the lead for all the other studios. In Belgium they colored all the characters on the computer, and we did some CG, like the Crom Cruach sequence and the Viking attacks. We had to use CG for the crowd scenes, but we tried to make it all look hand-made, keep it looking like medieval art. That was the goal.

Surprisingly, you're up against another hand-drawn animation ["The Princess and the Frog"] and two stop-motion films, along with "Up."

It's amazing to me. When we started making this movie in 2005, hand-drawn animation was basically dead, except in Japan. It's a mad year to be in the Oscars. Basically we're all in the shadow of "Up," which I think is a great movie. We kind of won big just by getting this nomination. We never thought that could happen.

"The Secret of Kells" opens March 5 at the IFC Center in New York, with other cities to follow.

Shares