A Democratic Senate bill to tame the financial markets would give the government new powers to break up firms that threaten the economy and would force the industry to pay for its failures.

Legislation unveiled Monday by Senate Banking Committee Chairman Christopher Dodd falls shy of the ambitious restructuring of federal financial regulations envisioned by President Barack Obama or contained in legislation already passed in the House.

But the bill would still be the biggest overhaul of regulations since the New Deal. It comes 18 months after Wall Street's failures helped plunge the nation into a deep recession.

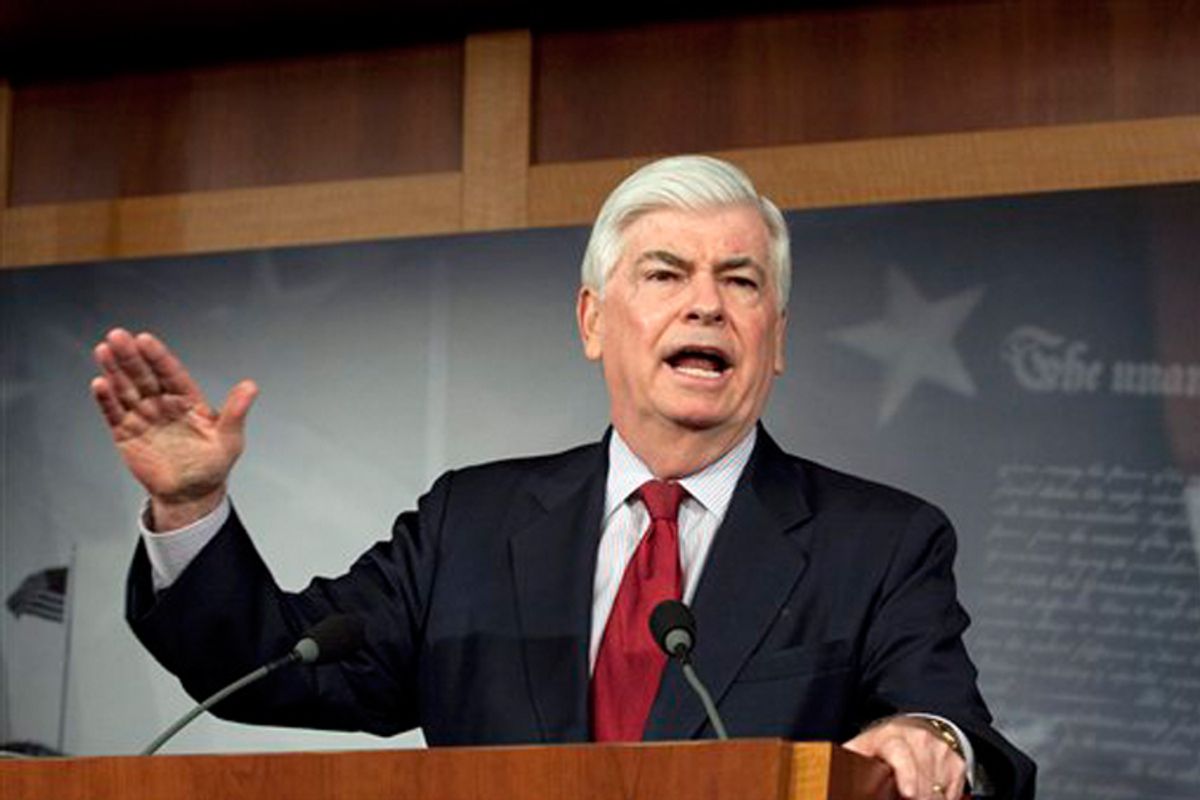

The Connecticut Democrat unveiled the bill at a Capitol Hill news conference.

THIS IS A BREAKING NEWS UPDATE. Check back soon for further information. AP's earlier story is below.

WASHINGTON (AP) -- Combining Obama administration and Republican priorities, the leading Senate author of a sweeping rewrite of U.S. financial regulations is looking for consensus with a proposal that neither side of the political spectrum is ready to embrace.

Sen. Christopher Dodd, the chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, plans to unveil a proposal Monday that expands the powers of the Federal Reserve but creates a consumer protection entity with less authority than President Barack Obama once demanded.

His draft legislation aims to avoid a recurrence of the financial crisis that brought Wall Street to the verge of collapse 18 months ago. It would restrict the size and interconnections of large financial institutions once deemed "too big to fail," tame previously unregulated shadow markets with new restrictions and create a dismantling mechanism for failing financial giants without a bail out from taxpayers.

While navigating in the middle of the road, Dodd has not won the support of Republicans. And Democrats inside and outside his committee, as well as consumer advocates are eager to change his consumer proposals.

"Members have to make up their minds," Dodd said Sunday in an interview with The Associated Press. "While they may not like everything here, I'm not going to give them much room to say we shouldn't do anything."

In looking for common ground, Dodd significantly shifted from financial regulations he proposed four months ago, when he called for a single powerful regulator to oversee all of the nation's banks and for a stand-alone consumer financial protections agency.

Instead, as preferred by the Obama administration, the Federal Reserve would gain oversight of all financial firms -- banks and nonbanks -- that are considered the biggest and most interconnected. For the central bank, the price of such power is losing supervision over smaller bank holding companies with less than $50 billion in assets.

Moreover, to the dismay of liberals and consumer advocates, the Fed would also house a consumer protection entity. That agency would be headed by a presidential appointee and would have an independent source of funds not subject to congressional appropriations. But its power to write regulations would be subject to review by a council of regulators that could veto consumer rules by a two-thirds vote.

John Taylor, head of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a consumer advocacy group, said Dodd was "capitulating to the industry's interests."

"He's offering a faux consumer protection agency that holds little promise to be effective in the long run," Taylor said.

In a nod to the White House, however, Dodd is expected to propose that states have enhanced ability to enforce consumer rules. State attorneys general and the Obama administration have called for such authority. Financial regulations approved by the House in December gave states more leeway to write and police their own consumer laws.

That consumer provision veered from the agreement Dodd and Republican Sen. Bob Corker had tentatively reached last week before Dodd decided it was time to stop negotiating and write a bill.

"We probably conceptually maybe agree on 85 or 90 percent of a bill," Sen. Richard Shelby, the top Republican on the Banking Committee, said Monday on CNBC. "It's a question of how do we move it forward." Besides differences with Democrats on consumer protections, Shelby cited "sticking points" on such issues as regulations of complex, previously unregulated transactions and giving shareholders a voice on executive pay.

Shares