In breathless language, Amnesty International urges the US to confront its "shocking maternal mortality rate." Entitled Deadly Delivery: The Maternal Healthcare Crisis in the USA, the report observes:

The total amount spent on health care in the USA is greater than in any other country in the world ... Despite this, women in the USA have a greater lifetime risk of dying of pregnancy-related complications than women in 40 other countries ... Amnesty International is sure that this increase is due to lack of access to medical care. The US government's failure to ensure that women have guaranteed lifelong access to quality health care, including reproductive health services, has a significant impact on the likelihood of having a healthy pregnancy and delivery.

Natural childbirth advocates, meanwhile, are sure that the rising rate of C-sections and other interventions is contributing to the rising maternal mortality rate. Amnesty International agrees, citing a "lack of information and autonomy" as the cause.

The report has made for frightening headlines: "Too Many Women in US Dying While Having Babies," reported Time, while CNN's headline called it "scandalous." However, it is not clear that maternal mortality is even rising, let alone rising because of decreased access to care or increases in the C-section rate. Review of the data suggests that changes in the way that maternal mortality is assessed may be leading to a spurious "increase" in maternal mortality. Moreover, a detailed analysis of the causes of maternal mortality casts serious doubt on either access or interventions as the reason for any rise. And while the statistics for African-American women truly are horrific (three and a half times the rate of white women) -- this disparity has existed almost since the statistics were first recorded 80 years ago.

In the last two decades, awareness that maternal mortality is underreported has grown. Vigorous efforts have been made to correct that problem. The CDC report Maternal Mortality and Related Concepts (2007) explains these changes:

In 1999, the coding guidelines used in the United States were expanded ... Along with the new definitions, the [new coding guidelines] introduced new details and categories in the cause-of-death titles associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium ... Furthermore, in 2003, the US Standard Certificate of Death was revised to ask explicitly whether any female death was associated with pregnancy, instead of relying on the person filling out the form to voluntarily provide that information.

The results of these changes are captured by the following graph.

The 1999 and 2003 changes in reporting of maternal mortality resulted in large "increases" that are not actual increases at all. They reflect the more accurate measurement of maternal mortality just as they were designed to do.

Yet some of the increase may be real. What about possible causes?

Curiously, the Amnesty International report provides no evidence that there has been a decrease in access to maternity services. Almost all states provide public health insurance for the duration of pregnancy in any woman who needs it. Indeed, 99+ percent of births take place in hospitals, so there is certainly no decrease in access to hospital care.

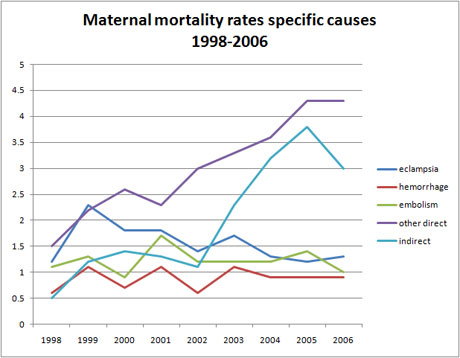

If decreased access to healthcare were responsible for an increase in maternal mortality, we would expect that the increase would be spread evenly among all possible causes of maternal mortality, but that's not what we find. The following chart shows maternal death rates from pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, hemorrhage, embolism (the three most common causes of maternal death) as well as other direct causes (all other obstetric complications) and indirect causes (from other medical conditions).

The most common causes of maternal mortality remained flat. In contrast, the categories expanded in the new reporting guidelines contributed almost all of the observed increase. This suggests that the "increase" reflects more comprehensive reporting, not an actual increase in maternal mortality.

What about an association between the rising C-section rate and rising maternal mortality? A graph comparing the maternal mortality rate and the C-section rate certainly shows a correlation.

But correlation is not causation. If the rising C-section rate were leading to an increased maternal mortality rate, we would expect to see C-section complications, such as hemorrhage and embolism increasing disproportionately. But as we saw above, both hemorrhage and embolism death rates remained flat.

What can we conclude about the observed rise in maternal mortality? First, we can see that the 1999 coding revision and the 2003 birth certificate revision captured more maternal deaths, as they were designed to do. Together they account for 80 percent of the observed increase since 1998 (5/100,000 out of a total change of 6.2/100,000).

To the extent that there has been a real increase, is decreased access or the increased C-section rate the causes of this increase? That seems unlikely since the increase was not distributed evenly among all causes (as would be expected if decreased access were to blame) nor is the increase predominantly distributed among common C-section complications (if the increased C-section rate were to blame).

Despite the rhetoric of Amnesty International, it is unclear whether we are experiencing an increase in maternal mortality rate or a crisis of any kind.

Amy Tuteur is a retired OB/GYN who also blogs for Open Salon.

Shares