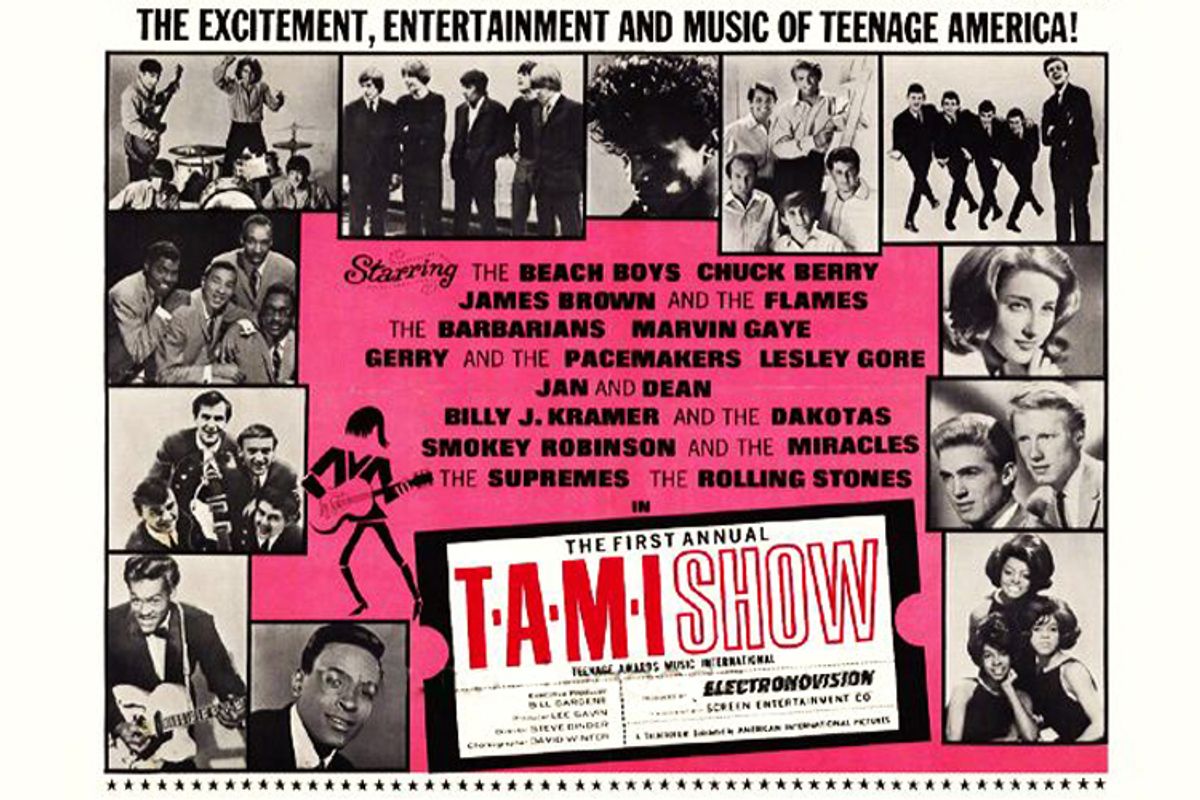

When I was a kid, my friends and I tried to out-lore each other with massive pronouncements about rock 'n' roll matters we knew little about. I was a "T.A.M.I. Show" guy — meaning, I had managed to see a VHS tape bootleg relic of the 1964 all-star extravaganza concert film that hardly anyone had seen since the days of "Beatles for Sale" and "Another Side of Bob Dylan." Which is to say, when the Beatles were still in black and white and Dylan had yet to plug in. I avowed that there was no finer rock concert film — never mind that the Beach Boys had made sure that their segment was excised — and I stumped for it as though I had a hand in future royalty payments. "Woodstock," "Monterey Pop," "The Last Waltz" — mere aperitifs compared to the full-on whisky kegger that was "The T.A.M.I. Show's" artistic bounty. I didn't care that its full name — Teenage Awards Music International — sounded both awful and totally made up.

One tends to be a bit of a moron at 13 or so when you're going on about your own personal canon, but "The T.A.M.I. Show" is now out on DVD, the Beach Boys are back in place, and I think I probably undersold the whole thing, actually. The film was directed by Steve Binder, who was later responsible for that 1978 Star Wars holiday cartoon special, the delight of many a YouTube-trawling stoner. "The T.A.M.I. Show" is a mess in its way, too, but in the manner of a rugby scrum or a goal line battle — the energy is intoxicating. And it looks like it was shot inside out — that is, the front of the stage might as well be backstage for all the attendant chaos, with bands setting up as other bands perform, and people racing in all directions for their marks.

Such scenes were familiar on the gala package tours that were the rock 'n' roll norm until the Beatles and Stones took over and a shift began away from singles and toward albums. All of a sudden, people had more stage-worthy material. "The T.A.M.I. Show" was a package show — the entirety of the two-hour film comes from one five-hour period of shooting — with the added wrinkle of an evolved social conscience. The Civil Rights Act had just passed, and so we get Chuck Berry and his Deep South locomotive rhythms in an opening battle-of-the-bands segment with Gerry and the Pacemakers, as white an act as any until the days of Bread.

Chuck Berry wasn't exactly the best guy, and the notes make an oblique reference to how he nearly jeopardized the entire undertaking just before the cameras started to roll, demanding more cash, and ready cash at that. But he could outclass just about anyone on the stage while still maintaining his standard ready-for-raunch persona. As he minces his way into the frame, he nudges his hips — very probingly — into the back of his guitar, as if to say, Ah, and now we're in. That's nice. I'm not sure what to compare it to. I wouldn't compare it to Gerry and the Pacemakers, who "inherit" — on the far side of the stage — Berry's "Maybelline" just as the master reaches the halfway point. The Pacemakers were the Beatles' big Liverpudlian rivals, and if you've not seen them perform before, you might find yourself at a loss to explain how this was possible. And I like the Pacemakers. But in the pop world, if you're not aging well, you're aging terribly, and it's like someone let the Pacemakers loose from a child's long-buried memory box.

Nostalgia sells, but the big, ever-timely dual theme of "The T.A.M.I. Show" is range and competition. You get Lesley Gore, who doesn't come off as twee as the Pacemakers, but who gets a proper stomping by the Supremes. "The T.A.M.I. Show" was an odd, one-off venture that you'd think no one took that seriously, but man — some real courage was involved for some of these acts to get up there and do what they do in the presence of acts they must have known did it so much better. Some, like the Barbarians — "all the way from the caves in old Cape Cod," according to MCs Jan and Dean — were probably so bemused that they were invited that they were mercifully unfazed. Their drummer, Moulty, had a hook for a hand, which led to a novelty single that has since become a classic for garage rock fans. Unlike most garage bands, who aped the Yardbirds and Them, the Barbarians basically just did their own brand of bashing, which borrowed heavily from Chuck Berry's school of riffing. I assume that they would have looted the Yardbirds and Them for everything they were worth, but those groups had yet to come along. The Barbarians are a mess, and they're fun. They also have no business being followed by James Brown and his crack band, with his crack dancing moves, and his Art Blakey-like drummer.

Brown didn't rehearse his segment — either he couldn't be bothered or he thought there was no need. He's pretty shameless — you'll see him stumble to the ground several times from exhaustion, having given his soul, strength, heart, etc., to the onlooking crowd of (mostly) white screaming teenyboppers. He actually has a "cape man," a guy who helps him up off the ground, wraps him in a cape, and encourages him to exit stage right, for a deserved rest. Brown wants no part of it, and ups the emotionalism, which, by the time of "Night Train," has passed from amusing to intense to "Oh my, he might expire up there." You can even see that his pants are starting to wear through at the knees. It's something.

The Rolling Stones wanted no part of following Mr. Brown, and told Binder and the execs. Brown thought he deserved the closing spot, not some bluesmen wannabes from England. No one listened, no one cared, save the musical parties. Brown then vowed to make the Stones wish they had never seen the States. Looking as calm and bored as if they were sitting down for tea, the Stones merely proceeded to play the greatest filmed set of their career. It's one kick-ass draw. Brown even offered his congratulations. I'd say that must have shocked the Stones, were it not for a look of total self-satisfaction that sets in on Mick Jagger's face around mid-set. You can practically see the arrivistes start to fancy themselves as full-fledged lords.

Colin Fleming's work appears in Rolling Stone, the Atlantic Monthly and the New Yorker. He is completing a story collection and a novel and can be found on the Web at colinfleminglit.com.

Shares