The politics of bank reform should be pretty easy to figure out: Wall Street isn't winning any popularity contests among voters these days, and Democrats -- with some help from their opponents -- have managed to create a simple narrative around which side wants to add regulations to the system and which side prefers the status quo.

But as the Senate struggles to move forward with legislation to rein in some of the worst excesses of the recent boom (and bust), it may bring not only good tidings for Democrats looking ahead to November. Yes, Republicans held together Monday evening in a unified stand against reform, blocking a procedural measure that would have allowed debate to begin on the reform bill -- which definitely seems to put them on the wrong side of populist public opinion. Still, Democrats have to watch out for some potential pitfalls along the way, or they could wind up missing what should be an easy political win.

For one thing, big Wall Street banks -- and everyone's favorite enemy, Goldman Sachs, in particular -- have given huge sums of campaign cash to Democrats in the last few years, favoring them over Republicans by a wide margin that's actually gotten more lopsided this cycle, even as Democrats push new regulations on the industry. Part of the reason Democrats have a majority in Congress is the help they got raising money from PACs run by Wall Street firms and commercial banks and their employees. At the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, for example, run by New York-area lawmakers since 2003, contributions from two industry sectors -- commercial banking and securities/investments -- accounted for 15 percent of the money raised in 2008, up from 5 percent in 2000, according to a Salon analysis of federal data collated by the Center for Responsive Politics.

Will that money dry up over Wall Street reform? Probably not, according to operatives and observers of political fundraising. Contributions are already on track to roughly match 2006 totals, says Sheila Krumholz, the center's director, and having the bank legislation up for debate only means Wall Street has more incentive to give money to candidates, which tends to be the way corporations express their desires. Besides, as one Democratic fundraiser points out, plenty of investment bankers still have personal relationships with lawmakers they've been giving to for years. Party committees, like the DSCC and its House counterpart, could take a hit. But Democrats already have a hefty fundraising edge over their GOP equivalents there. And at any rate, the investment bankers and hedge fund operators who have poured millions of dollars into politics in the last decade know the way Washington works; Democrats will still control the White House (at least for two more years) and most likely the Senate, even if they lose the House, which means campaign cash that tends to flow to whomever's in power will still be forthcoming.

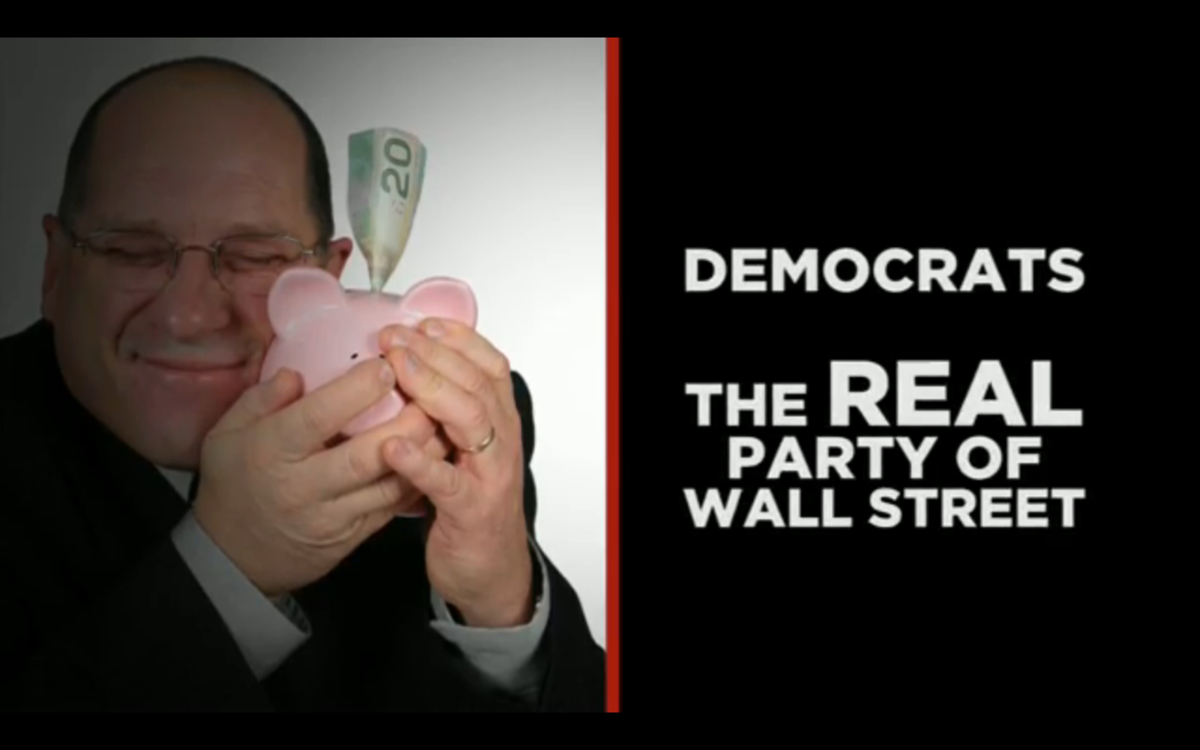

That doesn't necessarily mean Republicans will be able to convince anyone that the other guys are the party of Wall Street, of course. The GOP has been trying -- maybe a little too hard -- to pull off that very line. Here's a video the National Republican Senatorial Committee put out Monday to try to make the case:

But polling indicates it's not working that well. Democrats say they're starting to see signs voters care more intensely right now about cracking down on banks than they do about the economy -- which is probably mostly because the Wall Street bill is in the news, but it's still not a good sign for Republicans. People don't seem to be buying the GOP line that the reform bill will lead to permanent bailouts. (Michael Steele tried it again Monday, saying, "Senate Democrats stood with Wall Street," after the procedural vote.) This isn't the healthcare reform debate, where the GOP was happy to vote "no" over and over again; at some point, pressure will mount on Republicans to cut a deal and vote for something. Republicans didn't particularly want to talk about the politics of the vote Monday. "It isn't about the politics, it isn't about the messaging, it's about what's the policy at the end of the day," said Sen. Bob Corker, R-Tenn. Translated from political-speak, that usually means you're on the less popular side of a debate.

The public's impression of which party is on whose side may blunt the impact of the GOP's claims that Democrats are hypocrites on the issue. Plenty of Republicans voted for the 2008 bank bailouts, after all; now, Democrats can accuse them of refusing to reform the system so that won't be necessary again in the future. "It doesn't matter if you take their money -- it matters if you vote their way," said one Democratic strategist, speaking on condition of anonymity because the bill is still being written. "Taking their money and then voting to fuck them -- who says that's a bad thing?"

Of course, it's not entirely clear that the bill would actually do that. If Democrats give up too much trying to woo Republicans -- and their own Sen. Ben Nelson, who joined the GOP in voting against the procedural motion -- they might wind up with a bill that actually does stand with Wall Street. "I hope we just don't end up with a financial reform bill," said Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., who is pushing Democrats to limit the size of massive investment banks in the legislation, under the theory that "too big to fail" is also just plain "too big." "I hope we end up with a meaningful financial reform bill that, in fact, addresses the current situation." Bank reform may be one of those rare cases where politics and policy line up, and the obvious choice for Democrats is to stand firm and push for as tough a bill as possible. Which probably guarantees they won't.

Additional reporting by Emily Holleman.

Shares