Watch one of the many cable news debates about racial profiling, and it will probably go something like this: First a pundit will ask why, if there are patterns in who attempts terrorist attacks, we shouldn’t scrutinize some people more than others. Shouldn’t we be looking for the next Faisal Shahzad or Mohamed Atta? Then the designated opponent of profiling will point out that Richard Reid — or Timothy McVeigh, or the Unabomber, or whoever else — looked nothing like Shahzad or Atta. From there the conversation will devolve into a contest to see who can name more terrorists, until at some point the segment runs out of time.

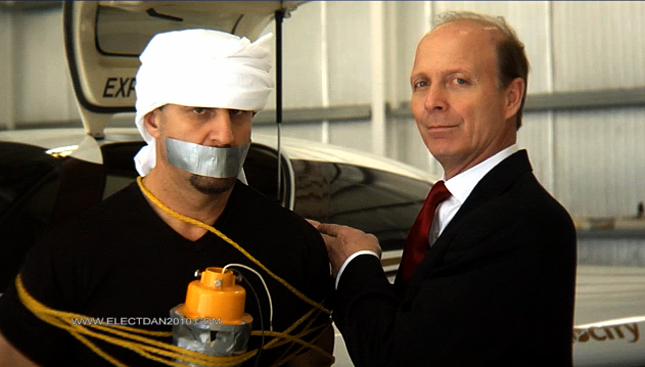

This is the debate over racial profiling that most Americans hear, but profiling opponents are foolish to play along with it. It doesn’t clarify the moral issues raised by profiling, and it doesn’t help to build a consensus against it. When these exchanges go badly for opponents, they simply play into the conservative narrative that liberals are beholden to a dogma of political correctness — ideologically committed to thinking that everyone is equally likely to be a threat, whatever common sense and experience may suggest. That impression is then eagerly exploited by the supporters of profiling, as in a Republican candidate’s brazenly pro-profiling TV ad this week.

But even when critics of profiling “win” these debates, they leave behind gnawing questions. What if the frequency of some crime really is higher among one group than another? What if profiling is an effective response?

These questions aren’t simply hypothetical, as Arizona’s harsh new immigration law has reminded us in recent weeks. Say what you will about the law, but if the point is to identify and deport those who are here illegally, it’s true that, as one Fox pundit put it, “You’re not looking for a blond-haired, blue-eyed Swede most of the time.” In other words, racial profiling is probably an accurate and effective means of enforcement. But if the problem with racial profiling is supposed to be that it’s inaccurate, then what’s wrong with profiling Latinos to enforce the immigration laws in Arizona?

This predicament reflects the fundamental mistake that racial profiling opponents have made. By allowing the debate to focus on whether profiling is rational, they’ve handed its supporters easy rhetorical victories. As another Fox contributor said of the Arizona law: “A lot of the critics are saying this is racial profiling. Duh! They’re coming from another country!”

Arguing over the accuracy of racial profiling also obscures the deeper and more menacing moral problems with the practice. Arizona’s new law, for instance, will ostracize innocent Latinos, entrench racial suspicions, and lend the government’s endorsement to hostile stereotypes about who “looks American.” It will serve as a regular and painful reminder to Latino Americans that, in the eyes of many, they don’t belong in their own neighborhood. It will poison the interactions between citizens and the police who are supposed to protect them and whose salaries they pay. None of these concerns are undermined by the obvious fact that Latinos are more likely than others to be illegal immigrants.

Similarly, the problem with using racial profiling to catch terrorists isn’t simply that, as Michael Bloomberg once said, “terrorists come in all sizes and shapes and forms.” After all, nobody has seriously proposed screening only Arabs or Muslims. Rather, the question is whether officials should consider ethnicity as one factor in deciding whom to examine more or less closely. We should exclude race and religion from those judgments not because everybody is equally likely to be a threat, but because it would be wrong to institutionalize the alienating suspicion already faced by innocent Muslims and Arab-Americans in their schools, workplaces and communities.

Making this moral argument means acknowledging that the decision to forgo profiling comes at a cost. In some cases, we could probably catch more criminals with the same investment if we were willing to single out people on account of their race. But while fairness may come at a price, we don’t have to pay in the form of more crime unless we want to. If we care about immigration enforcement and airport security, we’re free to invest as much as we want in them. It may simply cost us more — in time, money or convenience — to achieve the same level of success without racial discrimination. Many Americans are fond of the slogan that “freedom isn’t free.” Why should we expect that fairness will be?

Of course, sometimes racial profiling is simply baseless or counterproductive, and critics shouldn’t hesitate to say so. But a key lesson of the recent debate over the Arizona law — a debate the law’s critics are losing — is that profiling opponents can’t win the larger argument without taking a more principled stand. Racial profiling is wrong because whatever good it does is inadequate to justify the harm it causes. At the same time, it’s just not true that it’s inevitably ineffective or that it’s always grounded in racist falsehoods. By conceding that much, we could shift the discussion away from whether profiles are accurate and toward the real damage they do to American values and innocent people.

Ben Eidelson is a graduate student in philosophy at Oxford University, where his research focuses on the ethics of discrimination.