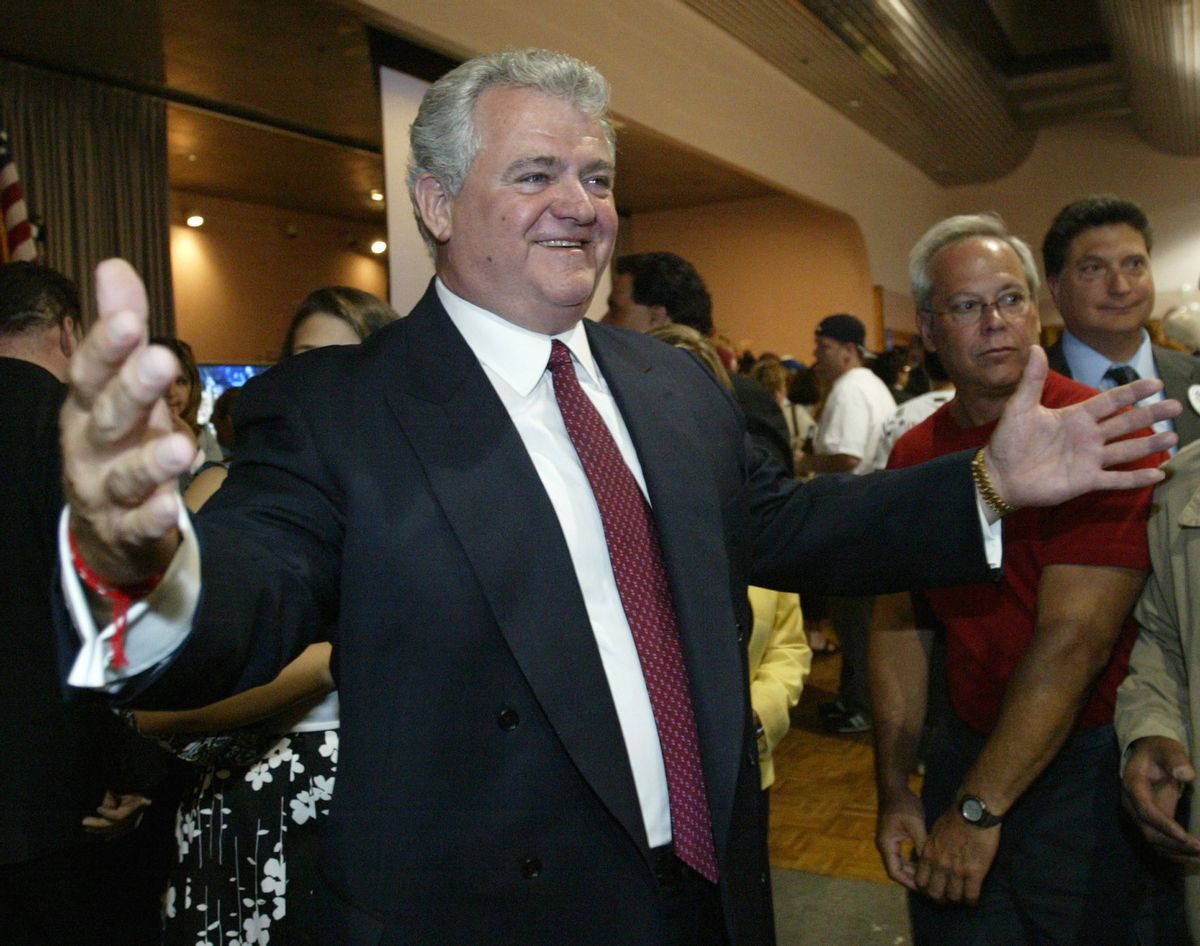

Being the king of Philadelphia isn't an easy job on a rainy day. Which means Bob Brady -- U.S. House of Representatives member, chairman of the Philadelphia Democratic Party City Committee and, most importantly on Election Day, leader of the party's 34th Ward operation -- had already gone through three changes of clothes by 3 p.m. Tuesday. He kept getting soaked while he was out working the polls.

The Democratic Senate primary here poses something of a test of the old urban machine style of politics that's still practiced in Philadelphia. For Sen. Arlen Specter to emerge with his new party's nomination, he needs to rack up a huge margin in Philly, and that means relying on Brady's operation to deliver votes. Rep. Joe Sestak, on the other hand, hardly even has a field operation in place.

But don't try telling Brady that means the machine didn't deliver. "I thought we were gonna steamroll this thing," he said Tuesday afternoon, lounging on a faded gray sofa in the back office of his ward headquarters in the Overbrook neighborhood of West Philadelphia. A few consultants and political hangers-on sat around, working their BlackBerries. (Between phone calls, Brady offered visitors Italian hoagies and homemade pepper-and-egg sandwiches that the widow of a former party committeeman had cooked up Monday night.) "It looked that way." But then Sestak started running the devastating TV ad with footage of Specter endorsing George W. Bush, and Sarah Palin, and suddenly the party establishment had a race on its hands. Now Specter's survival came down to Philadelphia, which meant -- Brady grumbled -- no matter how many votes he managed to turn out on a cold, dreary, rainy day, the City Committee would be blamed for not delivering enough if Specter loses. Even if Sestak wipes the map with the incumbent in the rest of the state.

After 30 years of working against Specter, some of the city's 66 Democratic ward leaders weren't that thrilled to be turning out the vote for him this time around. But Brady reminded them Specter had always delivered money for projects for the city, and for the region. And since that's the lingua franca of ward-level politics, they came around.

But the rank-and-file voters may be another story. Turnout was looking very low, in part because of the rain (though Brady told everyone in the headquarters that he still wasn't sure what actual effect rain has on elections) and in part because, by now, the only people who are really passionate about Specter are the ones who hate him. "The rank-and-file voters depend on the money that's on TV, and they molded them," Brady said, grudgingly giving Sestak's media operation -- the Campaign Group, which also worked for Gov. Ed Rendell and Mayor Michael Nutter -- credit for shaping the way the race was viewed by the broader electorate. (The new thinking in some political circles is starting to be that TV ads are passé, that money's better spent on more cutting-edge, targeted technology; listening to Brady, though, TV ads start to sound like some new upstart gimmick that ruined the traditional way of doing things.)

As turnout reports trickled in -- some reliable, some less so -- Brady didn't quite write Specter off. He made some phone calls to suggest places where people ought to go try to flush out more voters, and kept in touch with other power players. Like Specter's camp, the city machine was hoping the Philadelphia-area candidate for governor, Tony Williams, would draw some voters out, especially African Americans. But Brady didn't give the impression he thought the guy at the top of the endorsed ticket had done everything right, either. "I thought his organization would be a whole lot better," Brady said of Specter. Even before the polls closed, Brady had already started worrying about his next headache, which Sestak had set up on Sunday when he appeared to refuse to back Specter if Specter won. That would become a problem if Sestak wins, because Brady would have to ask Specter supporters to back Sestak anyway. "I have to ask them to make a commitment he wouldn't make," he said. (Sestak had actually clarified his comments later Sunday, but neither of the city's two daily papers had a reporter there when he did, so a lot of Philly politicos may not have heard about it.)

There's a reason, though, that Brady comes back to Philadelphia every night after the House concludes its business in D.C., and that he spent Tuesday alternating between being out in the pouring rain and working the phones from the far western corner of the city: It's part of the job description for being an urban political boss. And so is dealing with whoever the party's nominee is against Republican Pat Toomey. So whether it's Specter or Sestak, Brady's likely to be going through the same schtick on Nov. 2. If Democrats are going to hold the Senate seat, though, they'll have to hope he's got a little bit more turnout magic than he seems to be having on May 18.

Shares