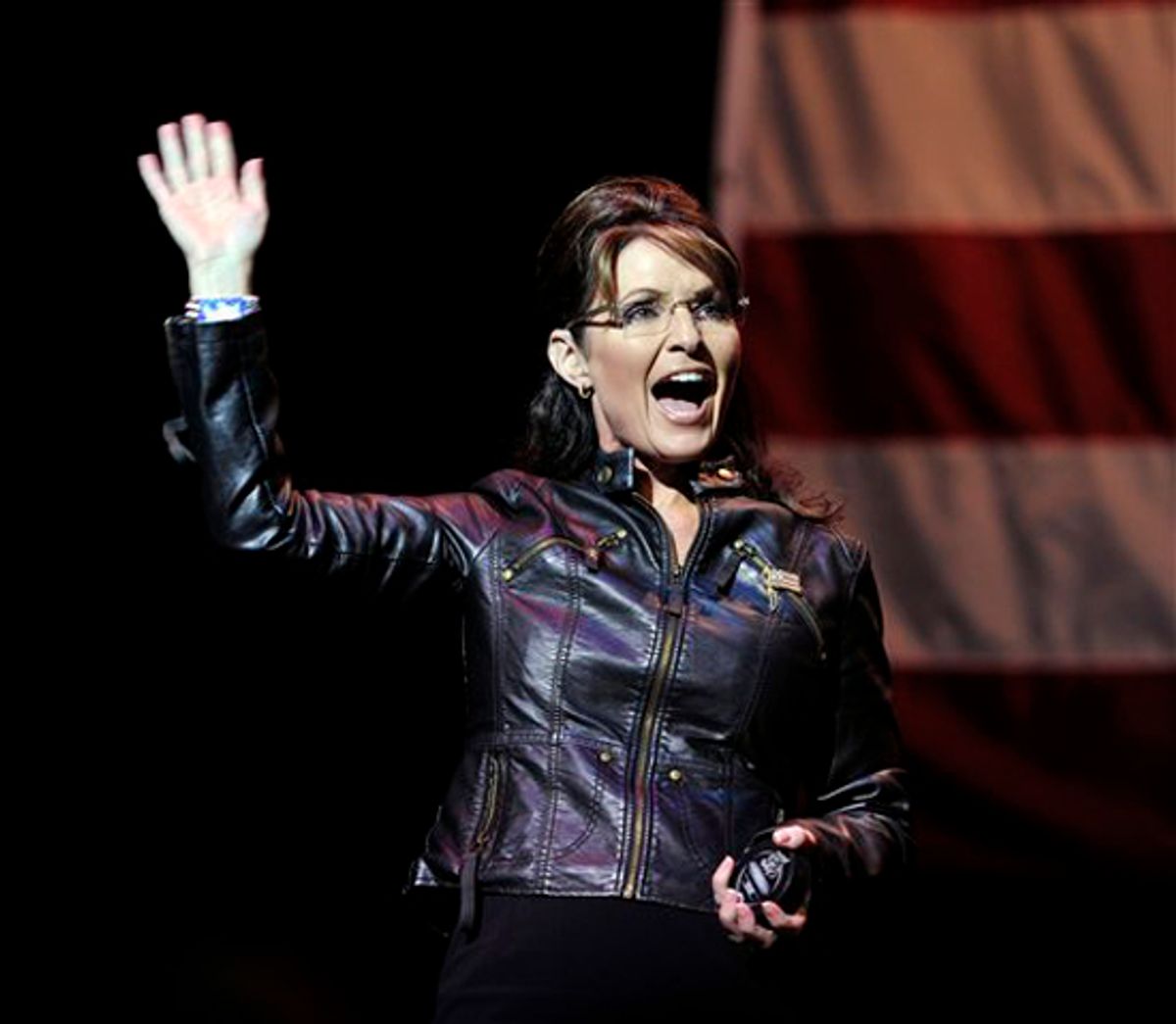

Sarah Palin has been making the moves on feminism again, talking in mid-May to the antiabortion Susan B. Anthony List about an "emerging feminist coalition" of conservative women, women she calls "Mama Grizzlies," telling the crowd that they were helping to return "the woman's movement back to its original roots ... You remind us of the earliest leaders of the woman's rights movement: They were pro-life." Harking back to (an imagined version of) first-wave feminism, Palin has been distorting second-wave ideology with a dastardly Opposite Day formulation in which those who support reproductive rights do not believe women capable of mothering and working simultaneously. (What happened to the old feminist bats forcing women to "have it all" against their will?)

Just like in 2008 -- when Palin attempted to horn in on the legacies of forerunners Geraldine Ferraro and Hillary Clinton, touting herself proudly (and truthfully) as a women's history maker, dismissing every criticism of her as sexist, making a speech about women's rights in Henderson, Nev. -- Palin's grab at feminist language has left-leaning women tearing their hair out. Recent weeks have seen pieces by Meghan Daum, Connie Schultz, Kate Harding, Taylor Marsh, Hanna Rosin and Jessica Valenti all chewing on the gristly question of whether Palin -- and more broadly, her conservative supporters -- can reasonably count themselves feminists.

But I've been plagued by a gnawing concern, even as I've appreciated the thoughtful ruminations by my colleagues about the differences between "feminism" as expressed by Sarah Palin and her right-wing antiabortion peers and "feminism" as espoused by left-leaning, reproductive-rights-supporting, progressive-policy-minded women and men. As useful as these efforts at definition and delineation are, I fear that they are just the beginning of what may be a battle more tricky and dangerous than many of us, who too often underestimate Palin and her cohort, imagine.

The problem starts with something that even critics who pooh-pooh Palin have acknowledged: that drawing defining lines around the women's movement is nearly impossible, since, in Valenti's words, "the tremendous range of thought in the [feminist] movement means there isn't a singular platform one can look to as a reference point." Feminism is not -- despite the best efforts of opponents to paint it as such -- a selective club. There is no entrance exam, no Sorting Hat, no membership cards. This is true for a number of sound reasons: Any movement that aims to represent millions of women needs to be able to bridge ideological, political, religious and ethical difference -- not to mention multiple races, religions, sexualities, and physical abilities.

But when it comes to securing a legacy, a keen grasp of feminism's complicated history and its multiplicity of identities does not make for great sound bites, the kind that right-wing bullies burp up with ease in heated television combat. Without some brawny -- unnuanced, uncomplicated and therefore inherently inaccurate -- backup, none of us is really in a position to say that one "feminism" is more real or faker than any other, and none of us can quite honestly point at anyone else and say "you don't belong," because, frankly, none of us "belong" to anything ourselves. What we are talking about is a battle over language. And the left -- perhaps because of a commitment to expressing a considered, thoughtful take on issues or perhaps because we are pansies -- does not have a winning history when it comes to battles over language.

Take "feminism" itself, a word that for 40 years has been kicked around by the right, especially by women on the right. The word, which indicates a movement that enfranchised and liberated women -- professionally, personally, socially, sexually and economically -- was, in the hands of its opponents, efficiently inverted to indicate sexlessness, humorlessness, and something fundamentally unfeminine. Having barely eked out survival into the 21st century, "feminism" has, thanks to the generation of young women who have, to my ear at least, reclaimed it with renewed vigor, surprisingly become almost hot again. Now the women who spent years perverting its meaning want a piece of it.

Years ago, women's rights activists ceded words that tied reproductive freedom to life and morality and were left with the limp language of "choice" – a word so fungible that it is now used to stamp everything from getting an abortion to getting a boob job as a "feminist" act. It's the very word that is being used as a weapon by conservative women who not unreasonably wonder why, according to the language to which feminists cling, their "choices" to support gun rights and religious teaching in schools are less valid than the "choices" of their feminist counterparts. Yes, there are a million responses to those questions; the problem is that the word "choice" has almost no place in framing them.

Neither will it help in explaining why contemporary left-leaning "feminism," which has in recent years strove (sometimes unsuccessfully) to shed its perceived white, straight, bourgeois husk and broaden to acknowledge and address other economic, racial, sexual and social injustices that affect women, will not broaden wide enough to include conservative women who believe in, or at least enjoy, some of the same things their liberal contemporaries strive for -- more equitable domestic partnerships, gender parity on playing fields and workplaces.

Of course, as feminist critics have pointed out, feminism is not just about enjoying rights, it's about supporting policies that make them possible -- whether those are universal healthcare (or, gasp, universal daycare!), better labor policies regarding family leave and flex time, a higher minimum wage and unfettered reproductive rights that all allow for full and equal participation in the democracy. On the subject of encroaching Sarah Palin feminism, my colleague Kate Harding wrote in an e-mail to me, "The goals of feminism are meant to benefit conservative women as much as anyone else. But no, conservative women who are actively trying to hinder progress toward those goals should damn well not be welcome in the feminist movement ... [S]aying that Sarah Palin's no feminist is not the same as saying that feminism isn't interested in improving Sarah Palin's life."

But more than those of us who are already declared feminists need to think about how we feel about women's social progress, its place in history and on the political spectrum; and those of us who have already thought about it a lot need to decide whether we're ready to express ourselves in aggressive ways, to act sure when we aren't sure, curt when we'd rather be considered, and mean when we'd prefer to be kind. Because though feminists rightly like to say that we don't draw prohibitive lines, that we don't have membership checklists, we are about to be called upon to draw a stark, crude line.

All this is to say that I am pretty damn nervous -- more nervous than I'd like to be -- about Sarah Palin's grab at "feminism." I have wondered in the two years since Sarah Palin's party-quaking introduction to America, especially while working on a book that deals with this subject in some depth, whether the initial visceral freakout of my left-leaning female peers about Palin was actually an animal prescience about the threat she posed -- not simply to the Oval Office, but to the very definition of what women's rights and advancement meant. I have wondered if the intensity of many Democratic women's reactions to Sarah Palin was actually a spine-tingling instinct about the conversation that now is underway -- the one in which "feminism's" enemies attempt to redefine and take it as their own, and gain traction in part because of the inability of its current stewards to cling to it with the necessary ferocity.

I wrote then, in the context of presidential politics, that I was afraid that Palin and the Republicans' embrace of "feminism" "could not only subvert but erase the meaning of what real progress for women means, what real gender bias consists of, what real discrimination looks like" and worse, that this subversion had been made possible in part because my own party "has not cared enough, or was too scared, to lay its rightful claim to the language of women's rights." The reference there was to the Democratic Party's sluggishness in celebrating the historic achievement of Hillary Clinton, its unwillingness to address the monumental nature of her presidential campaign or to acknowledge the often gender-inflected challenges she'd faced. What John McCain and Sarah Palin had done, brilliantly and terrifyingly, I thought at the time, was to move in on territory -- women, feminism, women's history -- that their opponents had been too reluctant to claim.

Now I feel that same concern on a broader scale. Many of us have lived through the decades in which backlash rhetoric has taken a stifling hold, have watched and listened as women who believe wholeheartedly in their own political, sexual and professional equality have distanced themselves from the word "feminism" and the movement that I wish had found a way to hold more viciously and more unapologetically to its own reputation. We have watched as the Democratic Party developed a strategy -- yes, a winning strategy, perhaps even more distressing -- of running moderate, and especially antiabortion candidates to gain a party majority, a strategy built on a fundamental divorce of Democratic Party politics from feminist politics.

So what, precisely, is to keep Republican women from coming in and taking a word, and a movement, to which they too are of course legitimate inheritors, and calling it their own? If Republicans want it more than Democrats do, then there is a good chance that they will gain it. "Feminism" belongs to those willing and eager to walk under its banner, the ones who put the energy and enthusiasm toward filling it with meaning and purpose. If the people most interested in owning "feminism" are Republicans, women and men who don't believe in a woman's right to control her health, or to receive the healthcare and economic support she needs, or to benefit from labor policies and protections that would enable her to work and earn to her full capacity, then I fear -- as I feared back in 2008 -- that feminism will be theirs.

On the occasion of Palin's speech to the Susan B. Anthony List, the organization's president, Marjorie Dannenfelser, said that 2010 will be remembered as the year in which conservatives reclaimed their country because "they loved this country so much they stepped up and took back and reclaimed America." These are the terms of the fight. We need to love feminism enough to step up and take it back.

In large part, it will be up to young women to enter into their first language fray. These women, often lambasted by their elders for having been born into a world of post-Roe privilege, have never had to tussle over "suffragist" vs. "suffragette," or "life" vs. "choice," but are about to get a chance to show that they can push and shove and yell with the best of their mothers and grandmothers.

But it can't be left to only the young feminists. There has to be a move toward ownership from other Democrats, from those women and men who have perhaps not yet named themselves feminists -- and perhaps who don't want to for very good reasons -- but who also do not want to see "women's rights" come to mean the exaltation of fetal life over female life and religion over science, who don't want to see "women's liberation" divorced from notions of equal opportunity and instead reframed as Ayn Rand-ian survival of the richest or most privileged.

If there is any hope of winning this particular war, we will need not just the valuable contributions of the Valentis, Schultzes, Hardings and Marshes of the world, but an army of thoughtful and committed Americans willing to lay claim to women's rights. We will need the Democratic Party, of late far too hushed about its claim to feminist history or any commitment to its future, to explain forcefully to their political and ideological opponents that feminism means an expansion of liberties for women, not a reduction, and that while Republicans are more than welcome to be feminists on feminist terms, those of us who have lived it love and respect it enough that we are going to continue to own it, thank you very much.

In the end, we can't say who's a feminist and who's not; that will be up to who throws the sharpest elbows, argues most nimbly, who is proudest to stand up and declare -- loudly -- the rightness of the side we're on, to demonstrate that women's progress is a moral and political imperative, and to crow that we have as fierce a stake in feminism's history and in its future as any Mama Grizzly.

Shares