Since the expiration of the federal homebuyer tax credit at the end of April, applications for new mortgages have cratered — down 35 percent in the last four weeks — to the lowest point since 1997. As Calculated Risk assiduously reminds us, the inevitable outcome is that the U.S. housing market is about to careen into its own imminent double-dip. For months existing and new home sales have been artificially stimulated by the tax credit. Now that’s over, which means inventories will swell again and prices will drop.

In a unfortunate display of bad timing, Stan Collender tells us at Capital Gains and Games that about three weeks from now 46 states will kick off their new fiscal year — and it won’t be pretty. “According to an analysis by the National Conference of State Legislatures,” reports Collender, “in 2011 all 50 states and Puerto Rico are facing an almost $90 billion budget gap.”

Unlike the Federal Government, individual states can’t run budget deficits. Cuts in public employment rolls and state services are inevitable — an anti-stimulus kicking in exactly at the same moment when the Obama stimulus starts to fade out.

In fact, as has been much discussed in recent weeks, the “stimulus” never had a chance to do much real stimulating in the first place, because the additional federal spending merely served to cancel out the contractionary effects of the state spending cuts already induced by the recession.

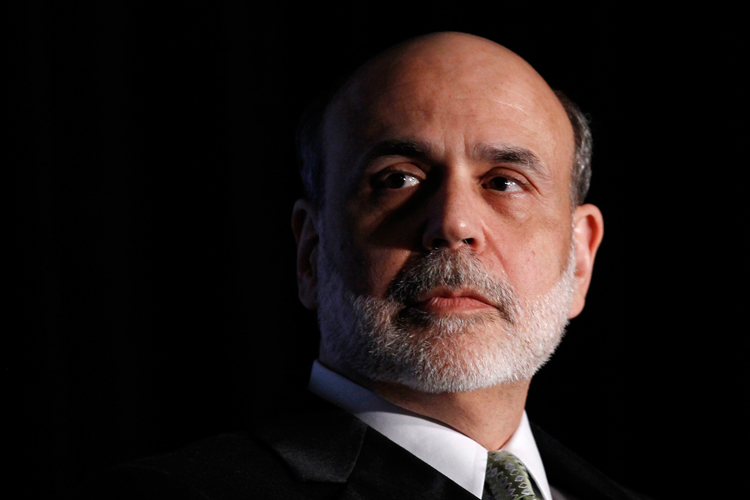

Throw in the decidedly unencouraging labor report for May, and you end up with a pretty forbidding scenario for the near future — without even taking into account the potential impact of the European financial crisis. Against this backdrop, then, how are we to perceive Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s testimony to the House Budget Committee today?

Bernanke is no Pollyanna. In his prepared testimony he noted that “there are significant restraints on the pace of the recovery” and he referenced both the expiring homebuyer tax credit and the state and local government budget travails. But at the same time, he expressed confidence that the economic recovery would continue, propelled by consumer spending and business investment. And he devoted the conclusion of his testimony to a strong push to deal with the federal budget deficit.

I don’t think there is anyone in the White House, or even among the chorus of progressive economists who favor more stimulus in the short term, who doesn’t realize that the U.S. federal budget deficit is a problem that must be dealt with in the long run. The argument has always been over the timing. Pivot to budget balancing too soon and you abort the recovery — which in turn would put further stress on the federal budget by crushing tax revenues and requiring additional safety net spending. On the other hand, if we take steps to ensure that the recovery is firm, thus boosting tax revenues, we end up with greater flexibility in the future in figuring out how to manage our finances.

Bernanke’s position is plain. Even though moderate growth in the economy in the near future won’t do much, if anything, to reduce unemployment, the time is now to address the budget deficit. And since Congress is manifestly unwilling to engage in any more aggressive efforts to bring down unemployment or otherwise stimulate demand, he’ll get at least half his way. Fiscal stimulus is dead for now. States will be on their own.

But the irony, or tragedy, or sheer absurdity of the situation is that while Bernanke and the rest of the deficit hawks may be successful in killing off fiscal stimulus, they most likely won’t match that success with actual deficit reduction, because Congress is just as unwilling to make the hard choices necessary to balance budgets — a mix of tax hikes and spending cuts — as it is to combat unemployment. So we’re going to end up with the worst of both worlds: We’re going to take a big risk of plunging the economy back into recession, without getting our financial house in order.