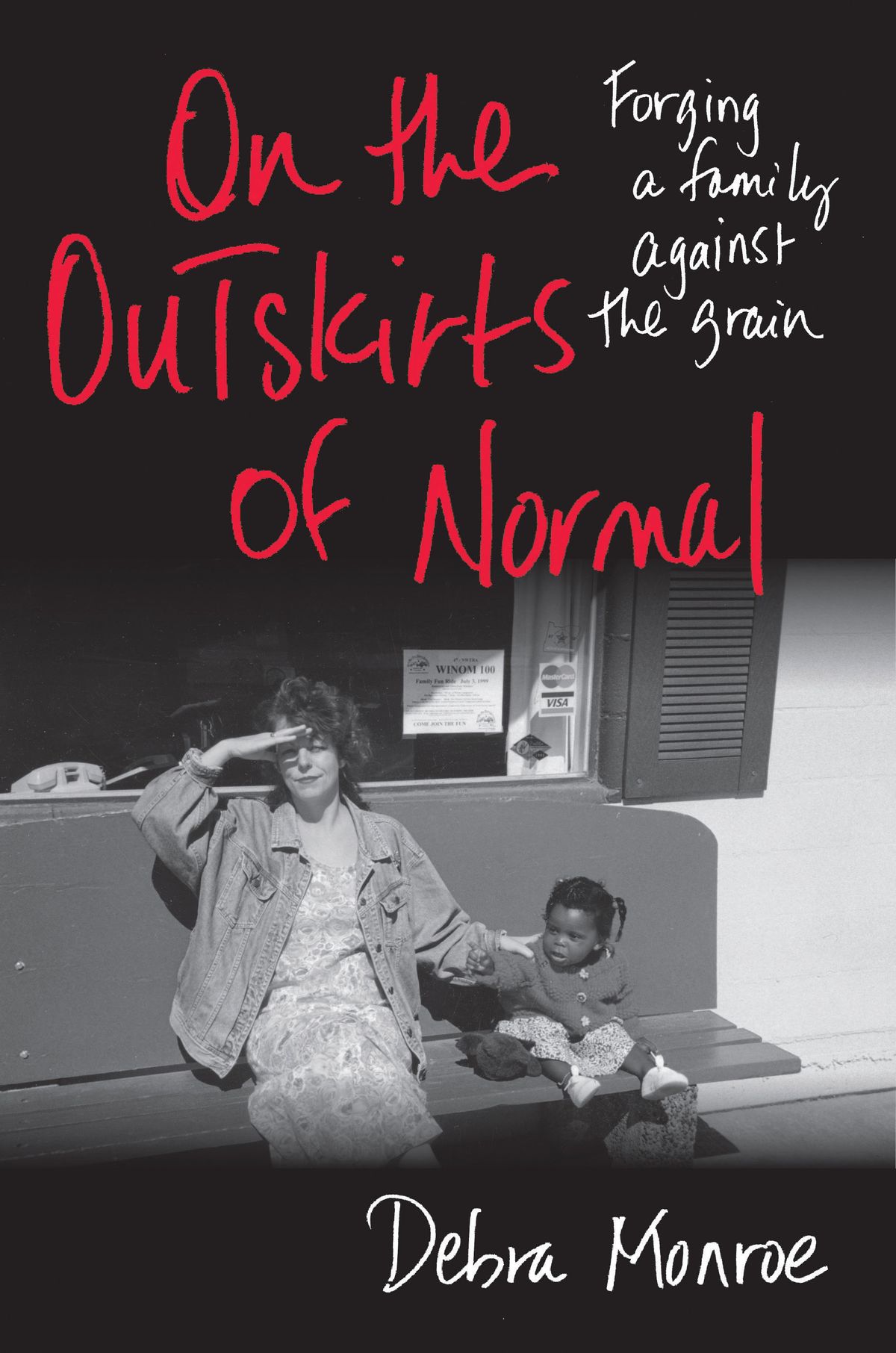

When Debra Monroe, a writer and a professor living in a small town in Texas, went to adopt a child, she was told that, as a single white woman, she could expect to wait about six years for a baby. Unless, that is, she was willing to do a "transracial" adoption. When Monroe said she was, the flabbergasted social worker initially suspected she was too dim-witted to know what she meant. "Black," she explained. Monroe again said OK. The social worker responded, "Can you take a baby in two weeks?"

It took a bit longer than two weeks for Monroe's daughter, Marie, to arrive, but once she did, their new family, described in Monroe's new memoir "On the Outskirts of Normal," was so unusual, she felt like a "minority's minority." Although most single adoptive parents are white women, only one percent choose to adopt a black child. This isn't solely a result of white racial discomfort; historically, the National Association of Black Social Workers has been vehemently opposed to transracial adoption. Placing a black child in white families, they have argued, is akin to "cultural genocide"; white parents, they claim, can neither teach black children their heritage, nor train them to live in a racist society.

Monroe pretty much gets it ("No one talks about it," she writes, "but it's the specter of history—humans bought and sold"), but by the time she was looking to adopt, during the mid-'90s, the Multiethnic Placement Act—which said that no child should be denied a parent or vice versa based on race or ethnicity—had just been passed. And she doesn't waste much time worrying about what might have been. "If a black mother had been available, my daughter would have fared better there. Probably. But why stop?" Why not also look for a married couple, with a stay-at-home mother and a dad with a fulfilling, financially rewarding job? "I could go on, romanticizing the parent I'm not," she writes. "Skin color is the least of it."

Monroe pretty much gets it ("No one talks about it," she writes, "but it's the specter of history—humans bought and sold"), but by the time she was looking to adopt, during the mid-'90s, the Multiethnic Placement Act—which said that no child should be denied a parent or vice versa based on race or ethnicity—had just been passed. And she doesn't waste much time worrying about what might have been. "If a black mother had been available, my daughter would have fared better there. Probably. But why stop?" Why not also look for a married couple, with a stay-at-home mother and a dad with a fulfilling, financially rewarding job? "I could go on, romanticizing the parent I'm not," she writes. "Skin color is the least of it."

The path she sets off on with her daughter may be far from conventional, but it is surely deliberate. The first in her family to go to college, Monroe went on to earn a doctorate, then became an author (she has written four books of fiction, and twice been nominated for the National Book Award). She was estranged from her mother when she refused to put up with her mother's abusive second husband, then had two failed marriages of her own, the second to a guy who ended up abusing her. ("In brief, people I came from tried not to hit or get hit, but we did, and we didn't talk about it—it was too private.") But by her mid-thirties, freshly divorced, she meticulously set out a plan for motherhood: she had a good job, bought a little yellow house in the country, and, along with hired contractors and newly-acquired skills with power tools, prepared for her new daughter.

Marie is a thoroughly wanted child, "spiffy, adorable and well-tended." Monroe gives her little girl a garden plot of her own, sews her clothes, and obsesses over her safety. She swiftly discovers that allowing her daughter to have "bad hair"—"the black woman's anorexia," one stylist explains—is a cardinal sin of white mothers parenting black children, and spends years learning the intricacies of corn rows, weaves, hot combs, relaxers, and sister locks, mostly through an underground network of home stylists, where she is sometimes welcomed and at other times greeted with disapproval.

But her Texas small town is still racially conflicted, and she has to deal with everything from busybodies (who always expect to hear "the story") to outright racism (one doctor makes remarks about the tainted gene pool in the black side of town; a clerk asks her, "Is that a crack baby?"). When a white pediatrician repeatedly claims Marie has the early symptoms of a rare, disfiguring disorder, Monroe can't shake the feeling that he is simply unfamiliar with black skin. But other people's opinions of their family become the least of their worries when both mother and daughter end up with serious (unrelated) health problems that further strain their fragile household.

Monroe doesn't waste much time justifying her family to others—her care and clear-eyed, unwavering focus on her daughter makes its own argument. Nor does she complain: whether she's packing her daughter onto planes to go on a book tour, or taking her along to a gig as a visiting writer, where the two stay with an old friend with questionable housekeeping habits, it's absolutely clear that this is the life she chose for them. "The sprawling mess of life is why we need stories," she writes, "a fleeting sense of order so we return to life with the unproven but irresistible conviction our mistakes and emergencies matter, so life might make sense too."

Shares