A precocious novelist, David Mitchell has the misfortune to be muddling toward his best work after being canonized as a genius by an ardent fan base. "Cloud Atlas," the book that established his cult, was an ingenious puzzle box of a novel, composed of pastiches of other writers' styles arranged in a nesting-doll configuration and containing at its center a vaporous puff of Zen. Its structure makes the book seem "difficult" without its actually being so, and as a result it lets its readers feel smart without unduly taxing their faculties. Perhaps the cleverest thing about "Cloud Atlas" is that it is not too clever.

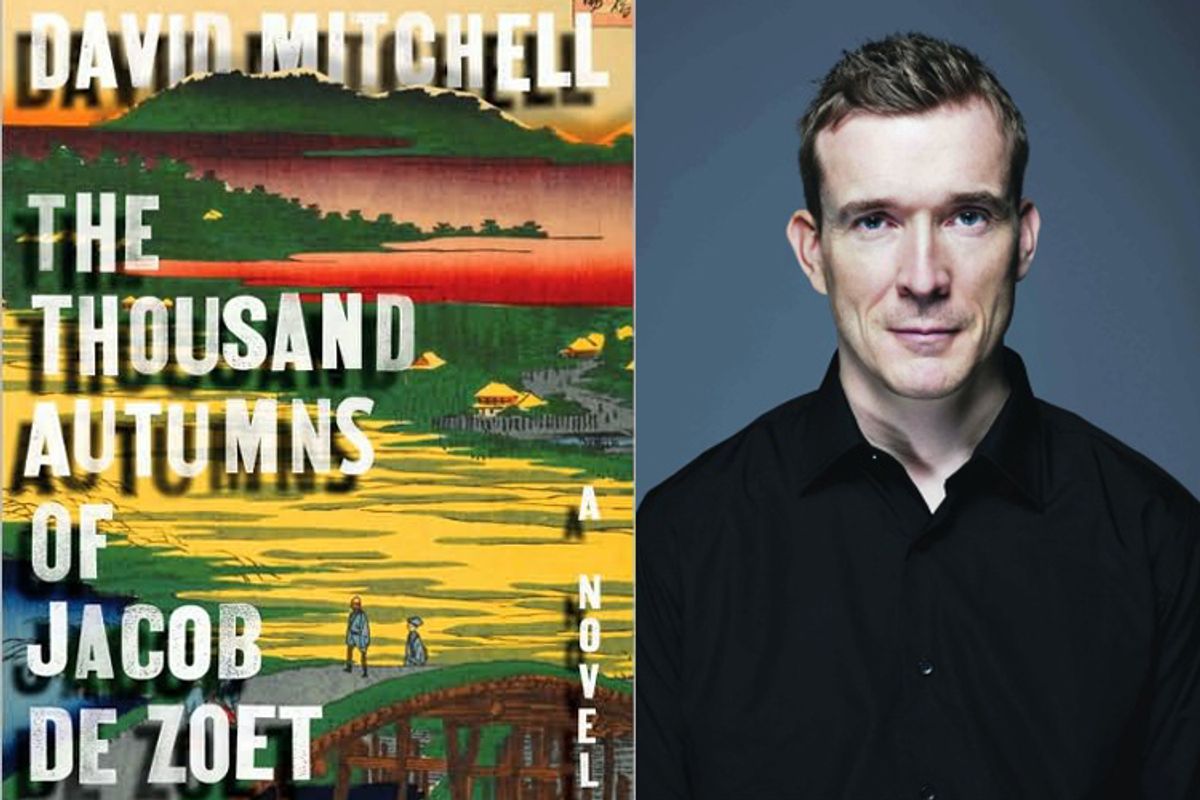

More important, however, "Cloud Atlas" is deliciously fun to read; this determination to beguile is what's most innovative about Mitchell as a novelist interested in playing with the form; he realizes that experimentation doesn't constitute a license to bore. Furthermore, in the books Mitchell has published since "Cloud Atlas" — the coming-of-age novel "Black Swan Green" and now a historical novel, "The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet" — you can detect an appealingly humble and questing sensibility at work. Booker nominations and best-of-the-2000s list placements aside, it's clear that Mitchell knows he's still figuring it out — that he isn't going to settle for becoming either the M.C. Escher of literary fiction or a postmodernist mandarin.

"The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet" is less successful than "Black Swan Green," but eminently worth reading all the same. It's a tricky book; the first part, some 170-plus pages, feels like a worthy but not especially exciting historical novel. It describes the experiences of the titular Dutch clerk as he arrives at Dejima, a small artificial island in Nagasaki harbor, in 1799. The island is an outpost of the once-formidable Dutch East India Company, and the bridge that joins it to the mainland is the sole avenue by which the Japanese are permitted to encounter Europeans (and vice versa) under the extreme isolationist policies of the Edo period.

An upright but likable Calvinist, Jacob serves the new chief of the compound in his crusade to clean up the skimming, bribing, swindling and smuggling perpetrated by the company's motley crew of hands and officials. This does not make him popular. Meanwhile, the community's doctor, a gruff paradigm of Enlightenment attitudes, has been allowed to teach European medicine to a small group of Japanese students, one of them a talented midwife named Orito Aibagawa. Jacob becomes infatuated with Orito and, despite his engagement to a woman back in the Netherlands, proposes that she become his "Dejima wife" — a necessarily temporary arrangement since no Japanese are allowed to leave the country and no foreigner can take up residence there.

This is a premise so overburdened with cultural baggage that it comes pre-scored with arias from "Madama Butterfly." Mitchell tries to pinch off budding charges of exoticism by making Orito somewhat physically marred by a burn (that is, she's not idealized) and by having Dr. Marinus ridicule Jacob as one of the "hundreds of ... besotted white men" convinced that his "adoration for his Pearl of the East is based on chivalry: behold the disfigured damsel, spurned by her own race! Behold our Occidental Knight, who alone divines her inner beauty!" Unfortunately, Jacob can't be defended effectively because his position isn't defensible; Dr. Marinus correctly tells him that his devotion would be best expressed by leaving Orito alone.

It also soon becomes obvious that the corruption in Dejima is incorrigible, leaving our hero with one purpose that can't be achieved and another that shouldn't. This makes for a passive protagonist and a somewhat hamstrung narrative until a minor character — a sinister aristocrat right out of a penny-dreadful melodrama — swoops in to kidnap Orito and carry the novel into an invigorating gothic register. The point of view shifts to Orito and several other Japanese characters, upending the view of things previously established through Jacob's eyes. There's a fortresslike convent up in the mountains where unspeakable rites are performed and a swashbuckling rescue plan.

Later still, the novel's third part flips back to Nagasaki harbor, where (in a development based on a historical incident) the captain of a British frigate attempts to take over Dejima and the Dutch monopoly on trade with Japan. (While Jacob has been pining and Orito languishing, the Dutch East India Company has gone bankrupt and Napoleon has conquered the Netherlands.) It's an opportunity for Jacob to prove himself, but events prove to be determined more by coincidence, luck and the unpredictability of compassion and self-sacrifice than by anyone's well-laid plans.

What knits together the three parts of "The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet" with their three disparate types of storytelling — genteel historical love story, gothic adventure and maritime yarn — is an underlying theme of confinement and isolation and how both may be transcended, even to the point of escaping the limitations of the body itself. The transmigration of souls is a device Mitchell has deployed more than once, but in this book the villain is the notion's foremost proponent; he literally steals souls.

For the more ethical characters in "The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet," it's not so easy. The novel is replete with islands and fortresses both literal and metaphorical. Bickering characters cooped up together in Dejima, in the convent, and aboard the good ship Phoebus demonstrate that if anything is universal to the human condition, it's office politics. There's also a single chapter, told from the point of view of a Malay slave, that contains some of Mitchell's best writing yet. This man, Moses, ruminates on what it means to have your hours, your family, your very skin and fingers, owned by somebody else, and on the refuge he's found in creating "a mind like an island ... protected by a deep blue sea." And right there Mitchell proves that of all the ways to bridge what another of his characters describes as the "intolerable gulf" between people, the imaginative adventure of writing and reading a novel remains one of the best.

Shares